By Nisha Arekapudi

It was just 50 years ago that women’s role in the economy began to drastically change. Reflecting striking social and industrial movements during the 20th century, they increasingly entered the formal labour force as both employees and entrepreneurs. As the number of working women grew, it became clear: global prosperity and women’s economic participation are inextricably linked. Their empowerment is directly correlated with countries’ ability to grow sustainably, govern effectively, and reduce poverty.

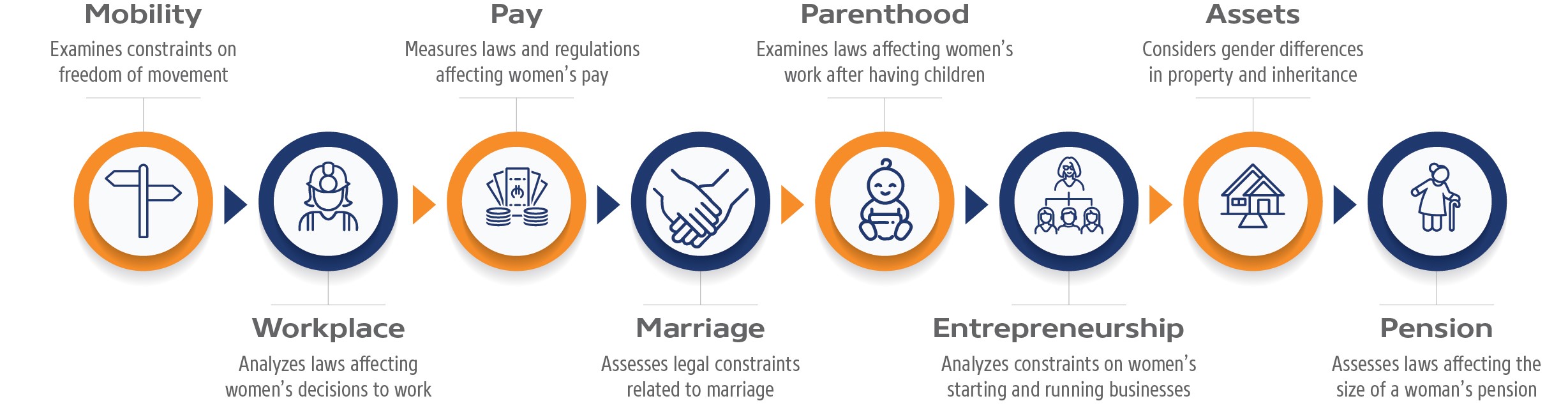

But as the world of work evolved, the law did not always evolve with it. In many places, the legal environment continues to limit women’s economic decision-making and employment prospects. This is the subject of Women, Business and the Law 2020, a new study from the World Bank Group. In its sixth edition, the project presents an index structured around the economic decisions women make as they experience various milestones. From the basics of movement to the challenges of working, parenting, and retiring, it highlights how the law restricts women’s economic opportunities. It also explores the relationship between legal reform and economic outcomes.

Figure 1. Index structured around the economic decisions women make as they experience various milestones

Scores at the country and topic levels give us both a global picture of progress toward gender equality and a starting point for where change is needed most. They show us that legal barriers all over the world are hindering women’s economic participation. In fact, in the 190 countries measured, the average woman has just three-fourths of the legal rights afforded to men. In the Middle East and North Africa, it’s only half. This has real effects on societies’ ability to boost economic growth. Our research shows that better performance in the areas measured by Women, Business and the Law is associated with more women in the labour force and a smaller wage gap. Where women and men are given equality of opportunity, improved development outcomes also ensue. This includes greater investments in health and education for both women themselves and future generations.

To achieve this, reform efforts could focus on those areas where change has been slow to occur. Under the Pay indicator, for example, the average score is just 66.1 out of 100. While most countries address wage discrimination in legislation, less than half of them mandate equal remuneration for work of equal value. This standard provides a broader framework than equal pay for equal work, as it allows a comparison between not only the same or similar jobs, but also between different jobs of equal value.

In order to close the gender pay gap, women must also be given the same choice of jobs as men. Legal restrictions on women’s employment remain on the books in 90 countries, barring them from working at night, limiting the work they can do in certain industries, or prohibiting them from working in jobs deemed too “dangerous.” In Lebanon, for example, women cannot skin animals. Colombian women cannot do industrial paint jobs. Azerbaijan even prevents women from driving buses with more than 14 seats.

Countries should also strive to better support women’s work after having children. The Parenthood indicator has the most room to improve, with a global average score of just 53.9. Ensuring job-protected leave of adequate length and pay for both parents is critical for a variety of health, economic, and social development outcomes. While 115 countries guarantee paid maternity leave of 14 weeks or more, the average length of paid paternity leave stands at just five days among countries that offer it. Only 43 countries have parental leave that can be shared by both mothers and fathers. Making sufficient leave available to both parents can help redistribute unpaid care work, sustaining women’s career progression and earnings trajectory. It can also lead to lower infant mortality rates, health benefits for the mother, and higher female labour force participation.

Fortunately, it is in these areas where we are seeing the most change. Fiji, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Zambia increased the duration of paid maternity leave to meet or exceed 14 weeks. With 16 countries total making positive strides, the Parenthood indicator was the most popular area of reform over the last two years. Similarly, 12 countries improved legislation relating to women’s pay. Among them, Germany mandated equal remuneration for work of equal value, and India eliminated restrictions on women’s ability to work in dangerous jobs.

Many also acted to protect women from violence, which can affect performance in the workforce, firm productivity, and ultimately economic development. Since 2017, eight countries have introduced legislation on domestic violence for the first time. An additional seven enacted new legal protections against sexual harassment in employment. Others strengthened already existing laws. In New Zealand, the progressive Family Violence Act introduced 10 days of paid leave for victims of domestic violence, giving them time to leave their partners, find new homes, and protect themselves and their children. Overall, reforms in every area measured by Women, Business and the Law took place in every region of the world, demonstrating that countries are committed to eliminating the inequalities that prevent women from contributing at their full potential.

And it was where it was most critical that the greatest number of reforms occurred. Of the top ten most improved countries, nine were from Africa and the Middle East. These traditionally low-scoring regions made the most progress toward gender equality in the last two years. Much work remains, however. In 1970, the global average Women, Business and the Law score was 46.5. Today, it is 75.2. At this pace, it will be another 50 years before we achieve legal gender equality at the global level. While the law is a foundational first step, it will take much longer to achieve its meaningful implementation.

By celebrating the progress made and emphasising the work still to be done, the Women, Business and the Law data serve as an important tool for those working toward reform. Gender equality is not only the right thing to do, it is the engine that will drive the faster, more equitable economic growth that we all desire. When women are guaranteed the same freedoms, choice of employment, and treatment at work as men, the global economy stands to gain enormous dividends. I am hopeful it happens sooner rather than later.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Women, Business and the Law 2020, a report of the World Bank Group.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by René DeAnda on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

I can name over 50 rights women have over men. I dare you to name just one legal right that is exclusive to men! Here are just 10 women have:

1) custody courts always give custody of children to the mother unless the father can prove to the court that she is unfit to raise the children.

2) Women who rape a man/minor and become pregnant as a result can sue their victim for child support.

3) Women get lesser sentences for equivalent crimes.

4) A woman can abort a fetus or give a child up for adoption without the knowledge or consent of the father.

5) In California a woman can declare a man her child’s father and the man only has 30 days to do a DNA test to prove to a court that he isn’t the child’s father and becomes responsible for the child even if he proves he isn’t the father later.

5) A woman can sue a sperm donor for child support.

6) A woman who doesn’t want to be a parent can get the government to force a man to support her child whether he wants anything to do with them or not.

7) Men have no reproductive rights.

8) Society at large believe women to be victims of domestic violence despite statistics showing that 70% of non reciprocated domestic violence being contributed by women.

9) Even though men make up 40% of domestic violence victims there are no state funded shelters for male domestic violence victims and are denied access to domestic violence shelters for women.

10) Women aren’t subject to selective service.