Disclaimer: Despite my long-standing professional interest, I’ve invested in bitcoin only briefly. Though I’ve earned a 30% return in just three weeks when I did so, I soon realised this investment was not suitable for my risk appetite. So, unfortunately, this is not the story of how I’ve become a bitcoin millionaire.

In the past few years, bitcoin has become equally famous and infamous worldwide thanks to the media hype that followed its rising and falling evaluations. From a historical high of $19,650 in mid-December 2017, it crashed to just $3,200 one year later, and subsequently recovered to reach $7,000 in mid-December 2019. Quite a ride! Yet, the most interesting changes in bitcoin run deeper than valuation swings.

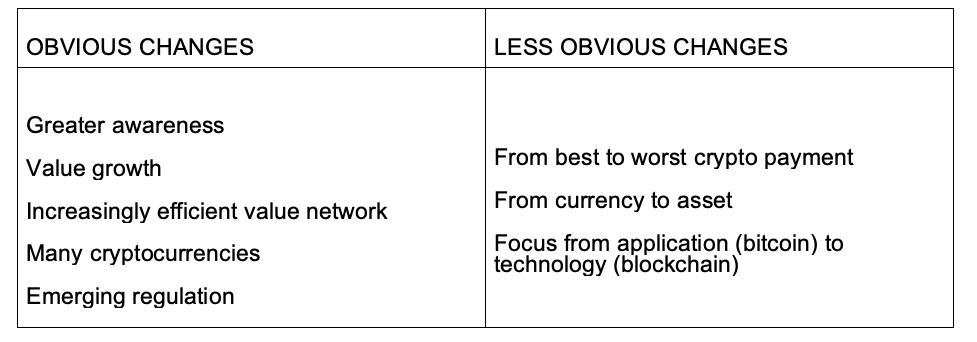

I became fascinated by bitcoin in early 2013. I first tried to buy some in October of that year (more on this below), and soon after, in 2015, I started teaching a course about bitcoin and blockchain. 2013 was an interesting year to approach bitcoin as things began changing really fast. These are the most dramatic changes I’ve observed since then, some more obvious and some less so.

The obvious changes

When I first attempted to buy bitcoin in October 2013, I was an assistant professor at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon. After finding a bitcoin trader going by the nickname of habibit_961 on a semi-secretive forum, I suggested meeting at a famous cafe’ on the city’s Corniche promenade and offered three different meeting times. At the meeting, I would have handed $500 in cash over to habibit_961 in exchange for three bitcoin that he or she would have almost instantaneously transferred from her or his wallet to mine. habibit_961 never showed up.

habibit_961 and I were to meet in person because, at the time, bitcoin trades were unregulated and occurred in a grey area, with a very dark shade of grey. Bitcoin itself was considered either illegal or a means to pursue illegal trades. At the time, the only platform known to widely accept bitcoin payments was a marketplace for illegal goods called Silk Road accessible on the dark web and shut down by the FBI short after. It was only a small community of tech enthusiasts who regarded bitcoin as the future of money in the making. I was one of them.

I found that keeping track of transactions on a public ledger that didn’t require any trust in the transacting partner nor in a third party sounded simple and yet so clever. The cryptographic and the consensus protocols that regulate how transactions are recorded on the ledger make this trustless system sustainable. (Bitcoin’s consensus protocol is based on proof of work. Miners use substantial computing power to solve a difficult mathematical riddle in order to validate bitcoin transactions and record them in a block. This happens approximately every ten minutes.)

In my mind, bitcoin was money 4.0. It had no intrinsic value, of course, as commodities (or money 1.0) did. It also didn’t have value because it’s backed by precious metals (money 2.0) or because it’s mandated by a government (money 3.0), but because it’s supported by a community.

It works!

The most obvious change since then is that you can now easily trade bitcoin and innumerable other cryptocurrencies (although many banks have since stopped the purchase of bitcoin with their credit cards). The increasingly efficient value network supported the diffusion of the bitcoin. Merchants began accepting bitcoin payments. Thus, bitcoin went from being a curiosity to functioning as a currency as it was meant to, albeit in a limited ecosystem. As a result, its value climbed up (I return to this point below) and public awareness expanded.

The less obvious changes

The more bitcoin’s popularity grew, the more its groundbreaking technological infrastructure – the blockchain – and its democratic governance became a liability.

The bitcoin blockchain designed to ensure safe pseudonymous transactions was meant to work on the computers and the internet available in 2008, when it was developed. For example, the mining of a block occurs approximately every ten minutes and the size of a block was set at 1MB, albeit allocated somewhat inefficiently, with almost 65% of data being details of the witness verifying the transactions. As the volume of transactions grew, the system could not scale and began to slow down, accumulating a backlog of transactions (called mempool) that cannot be included in the limited block space and so wait to be confirmed.

By 2017, most bitcoin miners had agreed that the system badly needed an upgrade. The governance system, however, requires unanimous support to introduce any upgrade. With the vested interest of thousands of miners at stakes, unanimous changes are very hard to attain.

Out of dozens of bitcoin improvement proposals (or BIP’s) to address the scalability problem, two went head to head. In simple terms, BIP 148 (also called SegWit) recommended the segregation of witness data from the block, to accommodate more transactions and make the system faster. BIP 91 (or SegWit 2x) further recommended expanding the block size to 2MB to make the system yet faster. If the two BIP’s would be compatible with each other, each miner could decide which one to follow, but users would still be able to send and receive bitcoin from nodes operating either protocol. (This is known as a ‘soft fork’.)

However, BIP 148 and BIP 91 were incompatible. Under BIP 91 the nodes would need to install a new software handling 2MB transactions, which could not be processed by the nodes following BIP 148. Failing to agree, the miners who supported BIP 91 had to split (undergoing a ‘hard fork’) and gave life to a new and better system, called Bitcoin Cash, which is incompatible with the original bitcoin system.

These events in the summer of 2017 highlight a few interesting and perhaps less obvious changes in bitcoin.

Not a currency

Being the original – hence the oldest – cryptocurrency and being resistant to change by design as just discussed, bitcoin is arguably the worst crypto payment system available. Not only Bitcoin Cash is superior to it, but dozens of serious cryptocurrencies inspired by bitcoin were designed to overcome its speed and scalability problems, ever since Litecoin, the world’s second cryptocurrency, launched in 2011.

As its performance and relative attractiveness as means of payment declined, bitcoin has increasingly turned into a store of value. This is supported by its deflationary nature. The number of bitcoins in circulation is capped and the rate of issue of new tokens is constrained by its consensus system. When the demand for bitcoin increases, since the supply is fixed, its price must go up. This is a very attractive property for a store of value. While it’s worth noting that the value of a store of value depends on its operating as a means of exchange, bitcoin is transitioning from a currency to an investment asset. For enthusiasts, bitcoin is the digital equivalent of gold. For regulators, due to its price volatility, it is more akin to a highly speculative asset.

The tech trumps the app

The final major change I noticed is that the relative importance of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies has steadily declined with respect to the blockchain. In 2015, I taught the blockchain to explain how bitcoin worked. In 2020, I teach bitcoin to illustrate how a blockchain works. This is not only a matter of zeitgeist, but more largely reflects the acceptance that decentralised ledgers (of which blockchains are type) are a general purpose technology with many use cases across industries and functions, way beyond cryptocurrencies. In fact, cryptocurrencies tend to have a very poor reputation among bankers and regulators. Blockchains on the other hand seem to hold great promise and many central banks are exploring applications.

To be fair, the growing popularity of blockchains should probably be also credited to other cryptocurrencies, such as Ether and Eos, designed to embed smart contracts. Smart contracts are both trustless and self-executing, and greatly expand what a system of tokens on a blockchain can achieve besides payments.

So, while in the early days there was hardly any mention of blockchains, which by some account already existed in some form prior to the bitcoin, the balance is now tilted. Bringing blockchains to the forefront of the ongoing digital transformation is arguably the greatest impact of the bitcoin so far.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by 5933179, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Alessandro Lanteri is is professor of entrepreneurship at Hult International Business School in Dubai and London. He also teaches for ESCP Business School and Oxford’s Saïd Business School. Alessandro works with governments and businesses across five continents. He holds a PhD from Erasmus University Rotterdam and a Master’s from Bocconi. His last book “CLEVER. Six Strategic Drivers for the Fourth Industrial Revolution” came out in 2019. His next one, “Financial Social Innovations: A new framework to understand the social innovations disrupting the world of finance, from crowdfunding to bitcoin,” comes out in 2021.

Alessandro Lanteri is is professor of entrepreneurship at Hult International Business School in Dubai and London. He also teaches for ESCP Business School and Oxford’s Saïd Business School. Alessandro works with governments and businesses across five continents. He holds a PhD from Erasmus University Rotterdam and a Master’s from Bocconi. His last book “CLEVER. Six Strategic Drivers for the Fourth Industrial Revolution” came out in 2019. His next one, “Financial Social Innovations: A new framework to understand the social innovations disrupting the world of finance, from crowdfunding to bitcoin,” comes out in 2021.

Be careful of people or platforms promising huge returns.