Thomas Jefferson said that ‘The care of human life and happiness… is the first and only legitimate object of good government.’ We agree with him, as did the LSE’s main architects – the Webbs and William Beveridge. So too do an increasing number of policymakers worldwide: only last October, the European Union’s Council of Ministers requested that all of its member states ‘put people and their wellbeing at the centre of policy design’.

This basic idea goes back to the eighteenth century Enlightenment and it is, in our view, the most important idea of the modern age. But until recently, it has not been easy to apply for lack of systematic knowledge about the causes of happiness. The new science of happiness is now changing all that, while at the same time modern psychology provides individuals with new tools to manage their emotions and their human relationships.

With these tools, millions of individuals and policymakers worldwide are already taking active steps to create happier lives – a world happiness movement is being born. In our new book, Can We Be Happier? Evidence and Ethics, we describe the new tools – the evidence on what causes happiness and how we can increase happiness, both through public policy and in our jobs and private lives.

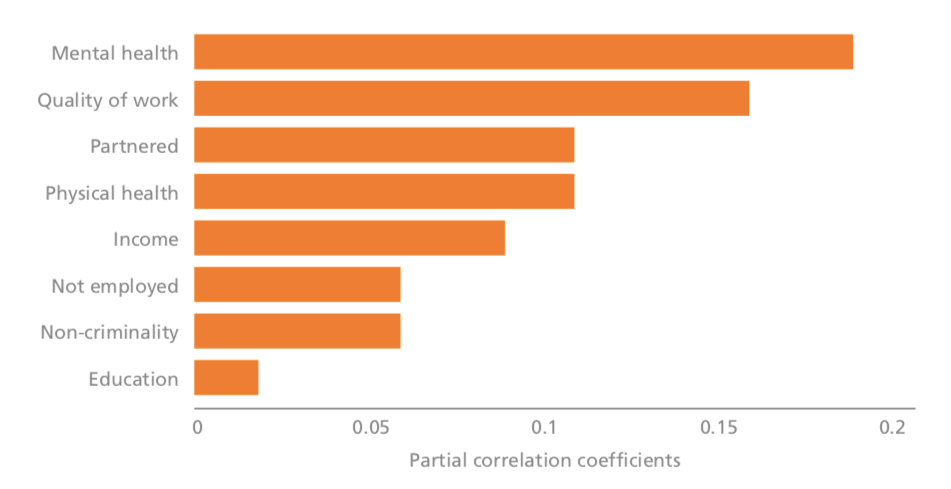

So what causes the huge variation in people’s life satisfaction? Figure 1 provides the answer for Britain, and the key factors are very different from the ones that most politicians assume. The biggest single factor is mental health – whether you have ever been diagnosed with depression or an anxiety disorder.

Figure 1. What things best explain the spread of happiness in Britain?

Source: Mainly the British Household Panel Survey

Next come human relationships – including the quality of your work and your private life – as well as your physical health. While all of these factors explain 18% of the variance of happiness, income inequality explains only 1%. Unemployment causes even less – it is a devastating experience but affects relatively few people.

We find this disconcerting since poverty and unemployment are the topics on which Richard has worked for most of his life. So is it possible that they are more important at explaining the scale of really low life satisfaction? The answer is No: the ranking of factors is essentially the same as in Figure 1. And this applies in all the advanced countries that we have studied. Moreover, if people themselves are asked what they worry about most, the ranking of factors is much the same (Sainsbury’s, 2019): money and debt come sixth.

But the next issue is this: the state can do something about income inequality and unemployment, but can it do anything about mental illness or the quality of work, or loneliness, or family conflict and domestic violence? To this, the answer is emphatically Yes: there is experimental evidence of ways in which we can

tackle all these problems and reduce the unhappiness they cause.

No one would propose ‘forcing people to be happy’, but we really should offer people help with the central problems in their lives. And in general, the costs of such improvements in social and psychological infrastructure are small compared with the costs of physical infrastructure. And the subsequent savings are often enough to repay the costs.

In our book, we review what can be done to raise happiness by many of the key players in society. We can start with teachers. Children’s wellbeing should clearly be a major goal for every school, and schools should be measuring their wellbeing on a yearly basis. To improve wellbeing requires major changes in the ethos in many schools, but it also requires the weekly teaching of life skills, using evidence-based materials.

To facilitate this, our research group sponsored and evaluated a complete course of life skills for children aged 11-15 called ‘Healthy Minds’, which has dedicated lesson plans and materials. In the evaluation, this passed the cost- effectiveness test of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) at a cost of only 3% of NICE’s maximum permitted cost (Lordan and McGuire, 2018; Layard et al, 2018).

After school, young people enter the world of work, where research shows that the worst time in the week is when workers are with their boss. This is shocking and in many workplaces we need a quite different management philosophy. A trial led by MIT shows that where workers are involved more closely in decision-making, their job satisfaction rises by more than 10% and their quit rate falls by a third (Moen et al, 2017).

But while good schools and workplaces can do much for mental health, at least a fifth of children and adults will still experience serious anxiety disorders or depression.

When this happens, there are now strong evidence-based psychological therapies (above all, cognitive behavioural therapy or CBT, which helps at least 50% of patients to recover). Because mental illness stops so many people working, these therapies save more public money than they cost (Layard and Clark, 2014).

Fortunately, we now have a whole range of effective therapies for tackling not only standard mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression, but also substance abuse, family conflict and domestic violence. We need urgently to make these evidence-based therapies available to all who need them – exactly as we do in the case of physical illness.

But humans are also social animals. Loneliness is a major problem in modern society, and town planners and community organisations can do much to promote social connections (Tan, 2006; Pitkala et al, 2009). There is much that different professions can do, and many more experiments are needed to increase their ability to contribute to a happier society.

Making all this happen requires a major rethink of the role of government. First, governments have to commit themselves to the goal of the people’s wellbeing. This means a new form of policymaking where policies are judged by the amount of happiness they produce per pound of expenditure.

Second, there has to be a wider view of the role of the state in which it not only helps people to be better workers, but also supports them in becoming better parents. The evidence is clear: the Scandinavian countries do better at this than any others. There, the size of the state is bigger and these are the happiest countries (Helliwell et al, 2019). There is no convincing evidence that low-tax countries are happier.

Will politicians listen? There is every reason that they should. Studies of European elections since 1970 as well as the vote for Donald Trump in the United States in 2016 show clearly that elections are decided more by the happiness of the people than by their incomes and employment (Ward, 2020).

Even so, there are limits to what public policy can do, and at least as important is what each of us does of our own accord. So what kind of culture do we want? The dominant culture of today urges us to strive to be more successful than other people. At the level of society, this is a zero- sum game. For every winner, there is a loser. That is not great for the losers, but it can also be very stressful for the winners. From the Gallup World Poll, we know that stress has increased worldwide despite much better living standards than a generation ago.

This makes no sense. Instead, we need a positive-sum culture where people get more of their happiness from making other people happier – and from concentrating less on external success and more on the inner feelings of themselves and others.

So we need a revolution not only in political philosophy but also in moral philosophy. Our aim should not be personal success, but rather to create as much happiness as we can in the world (including, of course, our own). This requires us to take better care of our own wellbeing but also that of others. Fortunately, modern psychology (and parts of ancient wisdom) enables us to do both. The basic idea is that our feelings are not just things that happen to us but can be influenced by how we think.

This old idea was more or less rediscovered by modern psychology in the 1970s. Aaron Beck, the founder of CBT, showed how we could observe our automatic negative thoughts. By concentrating more on positive memories and actions, we could transform our mood.

More recently, Martin Seligman has shown how these ideas can be applied to all of us. At the same time, mindfulness and other meditative techniques have taken off, enabling millions to achieve greater contentment with their lives. Despite appearances, a new gentler culture is being born.

But for cultures to flourish, they need to be embedded in organisations, where people meet regularly to remind themselves of what really matters and to feel supported and inspired. In a largely post-religious age, there are few such organisations representing the new, gentler culture. One of them is Action for Happiness: it has one million followers on Facebook, but its main activities are face-to-face groups.

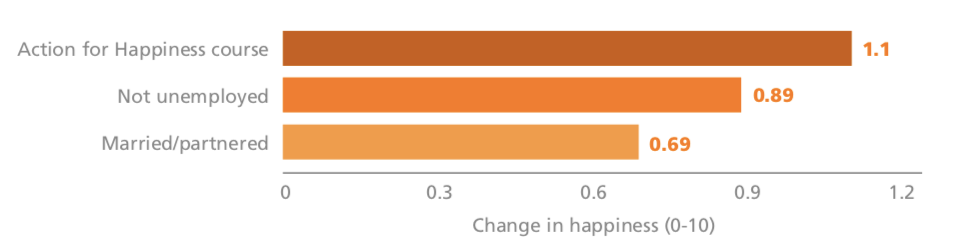

A group begins with an eight-week course called ‘Exploring What Matters’, which has been independently evaluated in a randomised experiment. Two months after the course, participants were found to have increased their happiness by over one point (out of ten) – more than the change that occurs when someone finds a partner or a job (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. ‘Exploring What Matters’ raises happiness more than finding a job or a partner

Source: De Neve et al (2020)

So we now have two powerful and converging trends, one top-down and the other bottom-up. From the top-down, we have policymakers and professionals paying much more attention to the outcome that really matters – how people actually feel about their lives. From the bottom-up, we have millions of people refocused on how to be happy and make others happy.

In our view, this is an unstoppable force and within a generation, we shall have better public policy and better lives. Let’s hope that LSE will have played a major role in this. Perhaps LSE needs a new motto: not ‘to know the causes of things’, but ‘to know the causes of happiness’.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post appeared first on CentrePiece, the magazine of the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance. It draws on the book Can We Be Happier? Evidence and Ethics.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Batel Studio on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Richard Layard is director of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance’s wellbeing programme and founder director of CEP. He is an emeritus professor of economics.

Richard Layard is director of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance’s wellbeing programme and founder director of CEP. He is an emeritus professor of economics.

George Ward is a PhD student in behavioural and policy sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a research associate in CEP’s wellbeing programme. His work aims to combine insights from economics, psychology and political science, and focuses primarily on the study of human happiness and well-being.

George Ward is a PhD student in behavioural and policy sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a research associate in CEP’s wellbeing programme. His work aims to combine insights from economics, psychology and political science, and focuses primarily on the study of human happiness and well-being.