One well-documented predictor of financial crises are credit booms and capital flow bonanzas. Indeed, many banking and current account crises (sudden stops) have been preceded by unusual expansion of domestic and/or external credit (see for example Reinhart and Reinhart 2008, Forbes and Warncock 2012, Schularick and Taylor 2012, Mendoza and Terrones 2012). To the best of our knowledge, however, not much research has focused on early warning indicators outside the realm of economic variables.

In this post, which is based on our research in Herrera et al. (2020), we discuss the role of political bonanzas (large increases of government popularity) in the run-up to financial crises, showing that this political variable can be helpful to predict crises. We propose new cross-country measures of government popularity, which covers more than 100 countries as far back as 1984. Specifically, we propose the use of the “International Country Risk Guide” (ICRG) sub-indicator of “government stability”, which measures “the government’s ability to carry out its declared program(s), and its ability to stay in office” and which we show is closely related to actual public opinion data for those countries and episodes for which actual government approval data is available (e.g. from Gallup).

Political booms predict crises

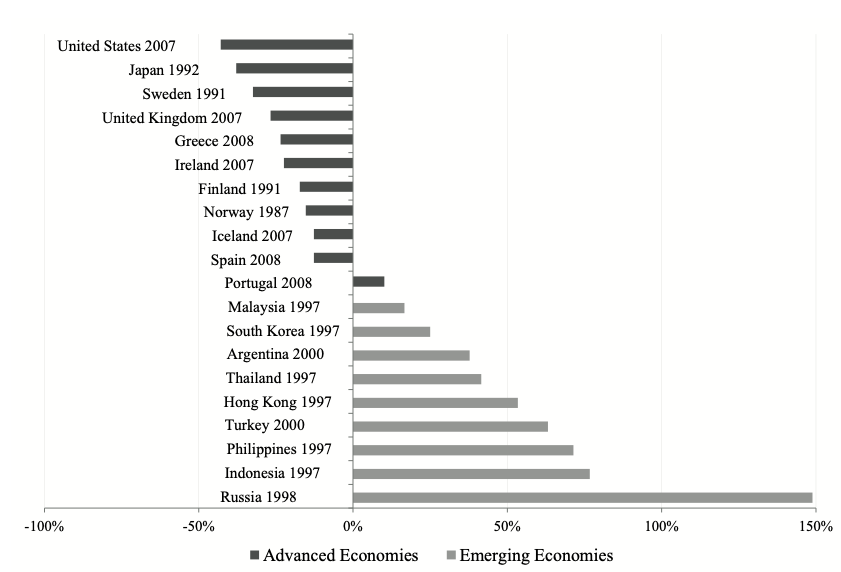

Our main finding is that “political booms”, defined as an increase in government popularity, precede financial crises. Improvements in the public opinion on the current governments increases significantly in the run-up to a country’s financial crash. Interestingly, however, political booms only predict financial crises in emerging markets, not in advanced economies. Figure 1 shows the cumulative percentage change of our measure of government popularity in the five years prior to the start of a severe crisis, as defined by Reinhart and Rogoff (2009). A stark difference between advanced and emerging economies is apparent. Government popularity increases substantially prior to severe crises in emerging economies, including all countries that went through the Asian crisis, but also prior to the severe crises in Russia and Argentina.

Figure 1. Cumulative change in government popularity (5 years pre-crisis)

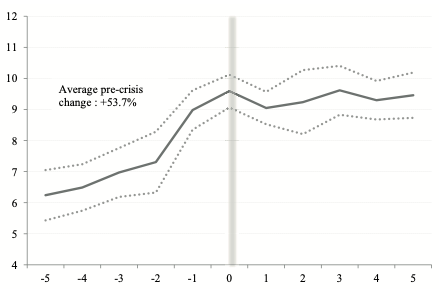

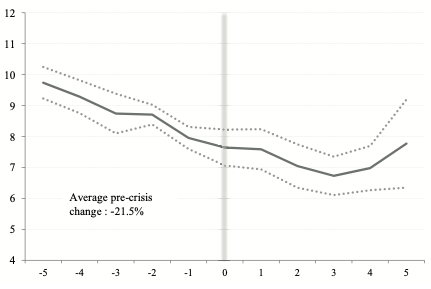

The first panel of Figure 2 shows for emerging economies that popularity increases in average by more than 50% in the five years interval before severe crises. Moreover, the 90% confidence bands are rather narrow, indicating that the dynamics are similar for episodes across emerging economies. The second panel shows the opposite trend in advanced economies, but with less economic and statistical significance.

Figure 2. Emerging economies: government popularity surrounding severe crises

This finding, which we confirm with a battery of econometric tests, controlling for several economic fundamentals and covering a broader sample of banking crises and sudden stop episodes back to the 1980s, is not only statistically, but also economically significant: one standard deviation increase in popularity in emerging economies roughly doubles the probability of a banking crisis. Most importantly, political booms predict future financial crises above and beyond credit booms in emerging markets. Indeed, the best model fit is achieved when including both credit booms and political booms. The two predictors jointly have much higher explanatory power than separately: an emerging market that experienced a political and credit boom at the same time is much more likely to suffer a crisis than a country experiencing only one of them.

To rationalise our new facts, we argue that governments have more and better information about the fundamentals in the economy than the public in general. In particular, governments know more about how sound is an economic boom their country may be experiencing. If the economic boom shows symptoms of exhaustion (for example because it is driven by speculation more than by productive investment opportunities, as highlighted by Gorton and Ordoñez 2014), then the ideal course of action for the government is to curve the boom by applying corrective measures that prevent or at least reduce the chance of a future crash.

Corrective policies, however, can be politically costly for a variety of reasons. Regulation, for instance, may reveal to the public that the economic boom for which the government takes credit is purely based on speculation, not on good policies. More specifically, we refer to “bad booms” as booms that are supported by unsound fundamentals and hence, have a higher chance to end in a crash. Since governments of poor ability/competence are more likely to generate bad booms, enacting regulatory actions becomes the tell-tale sign of poor quality of governance, and hence is politically costly. This popularity concern is a force that may prevent governments from enacting optimal regulatory measures to prevent crises: a government concerned by its popularity might thus prefer to ride economic booms even if that means a larger risk of a subsequent crash.

In line with the above logic, we document a negative correlation between financial regulation and government popularity. Especially in emerging markets, regulation tightening is associated with a decline in government popularity. Moreover, we show that, in emerging markets, most crises were preceded by regulatory loosening (not tightening), suggesting that loose regulation was one reason behind past crashes in these countries.

Emerging markets vs. advanced economies

Why do political booms precede financial crises only in emerging markets? We argue that governments with lower initial levels of popular support have more incentives to ride political booms simply because there is more margin for increasing their popularity than in advanced economies. Furthermore, if there is also high uncertainty about the government’s quality to begin with, then riding a boom also has more potential to change public opinion. Indeed, these preconditions are more typical in young democracies (including many emerging markets) rather than established ones – we show that government popularity in emerging markets is significantly lower than in advanced economies and also more volatile, meaning that the public is more uncertain about the quality of its politicians. In our model, this implies that popularity is more responsive to the perceived economic environment and to governments’ actions and policies. To match this rationale, we further show empirically that governments with lower initial popularity levels are more likely to experience financial crises in the future. This result holds even in the subsample of emerging markets.

In sum, emerging markets may be more prone to crises than advanced economies because their governments, having on average a lower reputation and more uncertain quality, can gain more in popularity from riding credit booms that are doomed to fail.

Concluding remarks

Concerns about popularity are believed to have a disciplining effect on policymakers and to generate positive economic outcomes. In contrast to this view, we show that popularity concerns may also have negative effects, increasing the likelihood of crises. This reputational mechanism should be also relevant in other fields such as redistributive policies, privatisations, fiscal stimulus, or taxation decisions.

Finally, our results are based on historical data. Looking ahead, current trends in advanced economies suggest that politics is becoming increasingly volatile and fractionalised, with apparent similarities to emerging markets, including the recent successes of populist politicians. This “downward convergence” of advanced country politics may result in more volatile, boom-bust prone economic policymaking and, thus, possibly, in a wider relevance of the “political booms gone bust” phenomenon.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Political Booms, Financial Crises, Journal of Political Economy.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image via PublicDomainPictures, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Helios Herrera is an associate professor of economics at the University of Warwick and an affiliate of the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). His research focuses on political economy, applied theory, macroeconomics, experimental economics, and financial economics.

Helios Herrera is an associate professor of economics at the University of Warwick and an affiliate of the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). His research focuses on political economy, applied theory, macroeconomics, experimental economics, and financial economics.

Guillermo Ordoñez is an associate professor of economics at University of Pennsylvania, and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He received his PhD from UCLA and joined Penn after a year at the Minneapolis Fed, and three years at Yale University. He is a macroeconomist working on financial crises and information imperfections in financial markets.

Guillermo Ordoñez is an associate professor of economics at University of Pennsylvania, and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He received his PhD from UCLA and joined Penn after a year at the Minneapolis Fed, and three years at Yale University. He is a macroeconomist working on financial crises and information imperfections in financial markets.

Christoph Trebesch is a tenured professor in macroeconomics and the head of research in international finance and global governance at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. He is also a research affiliate at the Centre for Economic Policy Research, and CESifo. His main research interests are sovereign debt and default, international capital flows, financial stability and financial crises, political economy and international financial institutions.

Christoph Trebesch is a tenured professor in macroeconomics and the head of research in international finance and global governance at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. He is also a research affiliate at the Centre for Economic Policy Research, and CESifo. His main research interests are sovereign debt and default, international capital flows, financial stability and financial crises, political economy and international financial institutions.