Before the pandemic, the evidence on remote working was that as long as the job is suitable for performing from home, most people are more productive when homeworking, but productivity is strongly subject to the employer policies and practices. At the same time, homeworking can save a business thousands of pounds a month per employee in office and other expenses, and can also raise employee morale and improve retention and collaboration. Remote workers also take fewer sick days and less vacation time, giving them more work days overall. The social advantages and disadvantages for work and personal lives are also well rehearsed in studies and in organisations themselves. It does not suit every job and all people, and often has unanticipated social downsides. Nevertheless, not surprisingly, we have seen a rising uptake in homeworking over the last ten years, not least because of improvements in enabling technologies.

Then we have to weigh the impacts of major emergencies. With every crisis, the anticipation of increased remote working has grown. During and after 9/11, many in the US were afraid to leave their homes. In 2008, it was predicted that higher petrol costs would lead to people not wanting to commute. Some predict that the high cost of living in major cities like London, Paris, Shanghai, New York, and San Francisco would lead to younger workers moving to smaller cities and working remotely. So now we come to 2020 and coronavirus. I was reading a report that more than 18 million companies in China resorted to remote work online by March 2020, with more than 300 million people using remote work apps. Clearly this is not a matter of choice, largely, but does it augur a permanent change in habits, not just for the mainland Chinese, but for us all? Here are my answers to questions being regularly reported on at the moment in the media.

Remote working has always been part of the tech landscape. In a post Covid-19 world, will tech companies move completely to remote teams? What about other types of business?

The pandemic is going to provide hard learning for us all. My experience of businesses in general is that hard learning is the only kind they really respond to, but even then not always! I see hi-tech companies moving faster to this mode, especially as having better technology platforms, they will have switched over even further to remote working in the pandemic, and will have the technologies, learning, and habits in place. But even they will discover that certain kinds of work do require in-person human interaction. Otherwise we would not have spent so many decades and so much money on office space, commuting, worrying about location, and HR practices. Meanwhile, I think the economics of remote and home working will be the clincher for all businesses, and assuming the technology will be readily available, the two key issues will be: is it more productive and does it cost less? One then has to add in some critical moderating social factors, for example, specific employee circumstances, social responsibility and legislation issues, childcare arrangements, impact on firms’ wider culture. It’s not just an economic question for businesses.

“… [with] no changes in productivity… cost savings from reduced office space, commuting downtime, more flexible hours (…) there will be more uptake of remote working.”

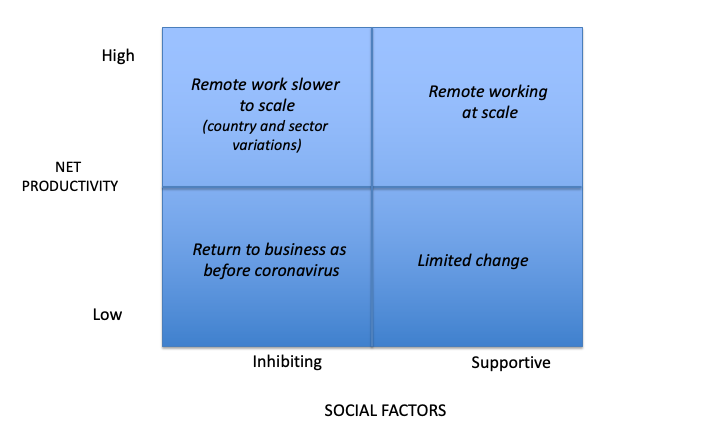

One way of generating scenarios in future studies is to pick two significant factors and plot them against one another. This then generates four possible outcomes. For me, we already know that the net productivity from remote working has proven to be quite strong and is likely to be even better if done to greater scale, though there is the chance that quite a lot of work will be included that is not suitable for remote working, and there may be some fallout when unanticipated costs arise. This is where the social factors kick in. These can be societal – acceptable norms, social legislation; organisational – which kinds of workers do we apply it with (see below), impact on our culture, does this kind of work need more interpersonal contact; or individual, e.g., worker preferences, type of job, home situation. Our graph suggests that the economic factor is likely to win out after the pandemic, at least for a while, but remote working will only greatly accelerate if the social factors are fully supportive. In some sectors, with some kind of work, it may well be that business will experience limited change, or even a return to pre-pandemic arrangements and levels.

Figure 1. Impact of coronavirus on remote working (RW)

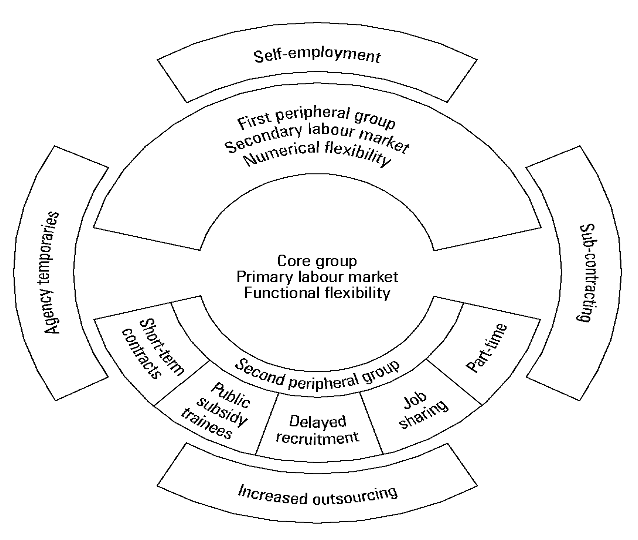

But it is more complicated than that. As long ago as 1984, John Atkinson posited a core/periphery workforce model to provide an organisation with functional, numerical and financial flexibility (see Figure 2).

I am expecting accelerating, more strategic moves towards what has already been done on this in the last 35 years. This means there will continue to be core full-time primary, internal workers who are integral to the functionality of the organisation. These will be functionally flexible and difficult to replace, due to high-level skills, knowledge and experience. These workers will have a big say in the degree to which they move to remote working. Meanwhile, there will be different types of peripheral workers. One group will be low-skilled, often part-time and flexible. Another will be made up of large volumes of agency staff, outsourcing and sub-contractors. We can see these workers operating in traditional functions such as cleaning and catering, but also in the gig economy and remote work contracting. Though not direct employees of the organisation, they are important to its functioning.

Figure 2. The flexible firm (after Atkinson, 1984, p. 29)

However, these two sets of peripheral workers have little bargaining power. Where it makes economic sense, organisations will use remote working as the cheapest, optimal alternative for harnessing these ‘peripheral’ labour pools. In so doing, managers are going to have to take into account some real challenges here – on modes of control, security issues, motivational challenges, and also corporate social responsibility concerns.

“Scaling remote working opens up vulnerabilities from the increased interconnectivity”

Are the collaboration tools we have available today able to scale to the levels we may need if remote working becomes the default state for most tech businesses?

This is a massive opportunity for the technology companies providing and improving these tools, and I see them as well capable of scaling the tools. The challenge is whether this can be done with the necessary security, ease of use and economics that users require. I am fairly certain that the systems will not be perfect, but, if I may say so, we are used to that already, so the calculation for business users is the trade-off between all these factors.

Have the security issues for mass remote working been assessed yet? Do we have adequate systems in place to protect businesses and their customers?

We know security is never 100%. Scaling opens up vulnerabilities from the increased interconnectivity, not least bringing in a lot more users who will not have security as their primary concern. I find that, with increasing knowledge about levels of organisational security, the more anxious I have become. Then, when organisations start doing something new, they invariably end up prepared quite well for the last war, as the saying goes, but not for the next one. I think it’s a big worry point if we move to mass remote working, and really should not be downplayed when people start marketing the brighter future to be had.

Could Covid-19 hasten the use of automation across many businesses in the tech sector?

Firstly, we know that historically it takes 8-26 years to see 90% adoption of a particular technology set across the main global economies and sectors. So, if automation seems a slow train coming, there is nothing surprising about this. It’s not just about the capabilities of the technology. We work in organisations with at least seven major silos. So key here is the organisational capability to change skills, processes, structures, managerial mind-sets, existing technology, culture and data, and align these to optimise technology deployment. As digital transformation efforts have demonstrated over the last ten years, this is a difficult series of challenges, at a time when many organisations have declining absorptive capacity to innovate and do something new, in any major way. After the pandemic, many organisations will have to return to the basics – re-establish finances, recover customers, refresh products and services, re-engage the workforce. For many, this will distract them from further investments in technology for some time to come. Others will reach for automation as an action lever in response to these pressing business imperatives. I think that about 20% of the organisations we have researched who lead in automation and moving to digital business will move even faster, not least because they have a better starting point, the experience, and the better financial performances to do so. Not all these are hi-tech companies!

Taking a bigger view, the pandemic is likely to be an accelerator towards automation and more remote working. But faced with the fundamental question now being asked, that seems too easy an answer. The fundamental question for businesses at the moment is: how long will the pandemic last and what are going to be its short and long terms impacts on the global and more local economies? I can only promise a guess at answering the riddle. More accurately, I would suggest that a productive way of looking at this is through risk assessment.

“… the internet and remote working certainly now have the capability to support us in the new crises that we are going to face in the 21st century.”

The fail-safe assumption is that it’s going to last at least a year, have enormous short-term impacts because of what Ian Goldin calls the butterfly defect – our global interconnectedness means that we cannot escape even small changes in parts of the globe – and some irreversible long-term impacts. Meanwhile, quite a lot will return to what will feel like ‘business as usual’, that is, pursuing what we have set up our businesses to manage, and to what customers want to return. But there will be changes in the business environment to which businesses should respond. As one example, if the technology becomes cheaper, easier to use, more accessible and good for scaling, that might cause businesses to adopt it faster. It is quite likely that this will happen, as one product of the pandemic will be the trials of the technologies in real-life situations. Innovation enjoys a crisis, That is why so many technical innovations came out of World War II.

Some working trends will emerge from the pandemic experience. People will have adapted to remote working, learned to leverage the advantages and mitigate the risks. This favourable trend could become allied with businesses experiencing no changes in productivity, and reckoning dramatic costs savings from reduced office space, commuting downtime, more flexible hours and working. If so, then there will be more uptake of remote working.

One emerging risk is the failure of multiple businesses across sectors, though some sectors will emerge in better shape than others. For many surviving business, the option might be to have fewer core workers and move many more to periphery status and further redesign work and the control of work, using advanced technologies. This again will see the greater uptake of automation. As I said, these are only some of the possibilities, and we need a thorough risk assessment of future risks and responses, to get further to answering the fundamental questions we are being asked by this pandemic.

Is the future of work remote, flexible environments?

I think that since the birth of the internet this has been one important, unavoidable trend in the future of work. It already has a history of adoption in different circumstances, and of challenges, failed experiments, and successful deployments for specific tasks. The issue businesspeople are now learning about is what it takes to cope in increasingly unstable, volatile, uncertain environments. Too many of us get carried away with upward economic growth trends, and do not build enough resilience and default actions into our financial management, business operating models, strategic aspirations, and how we engage our diverse workforces. I do think that the wise businesses will invest in remote flexible environments not just because of the net productivity gains, and the social acceptance, but also because it offers a default way of operating in case of future, more or less unanticipatable, crises, disasters, and events, natural or otherwise. I am not sure that the internet was really developed to help us cope in the event of nuclear war – the story of emergence is much more complex than that – but, the internet and remote working certainly now have the capability to support us in the new crises that we are going to face in the 21st century. If by the end of the year it proves otherwise, then we really do have work to do.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by InstagramFOTOGRAFIN, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Leslie Willcocks is professor of work, technology and globalisation in the department of management at LSE. He is a leading global researcher on technology at work, globalisation and ITCs and innovation and is a recipient of the PwC/Michael Corbett Associates World Outsourcing Achievement Award. He is co-author of 65 books, including four on automation, the latest being Becoming Strategic With Robotic Process Automation. See also his website.

Leslie Willcocks is professor of work, technology and globalisation in the department of management at LSE. He is a leading global researcher on technology at work, globalisation and ITCs and innovation and is a recipient of the PwC/Michael Corbett Associates World Outsourcing Achievement Award. He is co-author of 65 books, including four on automation, the latest being Becoming Strategic With Robotic Process Automation. See also his website.

In many ways it is surprising home-working has not been more common. Getting a grip of the overall picture is not helped by confusing and inconsistent definitions – Eurostat and the ONS seem to be using different criteria, while the stats sometimes include both people who use home as a base and people who do work in the home. Much of the former is associated with self-employment. My guess would be that some employers will have found home-working works well and will be more inclined to extend it to those who in their workforce who want to do a bit more. Some may even want to work most of the time from home. I suspect this will be one of the few permanent legacies of the crisis, but who knows?

I’m pretty sure this really is our new life. I assume 2020 is going to be the most digitized year. While it turned out that many managers were not prepared for remote work, now it seems that everyone is getting used to it. So yeah, definitely the new normal.