UK dividends paid out in 2019 reached nearly £100bn, an all-time high, with nine out of ten sectors raising dividend payouts (Darbyshire, 2020). At the same time, there have been numerous reports of companies such as Carillion, Thomas Cook, Woodford Investment Management, and BHS paying dividends that were unwarranted by underlying financial health.

Following the unprecedented effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the economy, the European Central Bank ordered eurozone banks to freeze dividend payments and share buybacks. The Bank of England has not yet followed suit and dividend payments for UK lenders, including Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds Banking Group and Royal Bank of Scotland, may still go ahead as planned. Companies are seeking ways to safeguard dividend payments, with Royal Dutch Shell securing a new $12bn credit facility to boost its available liquidity and maintain the existing dividend payout policy. Other companies however, such as Marks and Spencer and Delta Air Lines, have cut their dividend in recent weeks amid rising need to conserve cash, and for fear of a backlash from stakeholders if they reward investors while seeking government help.

The economic unit at the Bank of England has long been expressing concerns at the evidence that dividend payout ratios seldom fall, and that the satisfaction of short-term shareholder returns has become an underlying reason for what is called the dividend smoothing, almost irrespective of profitability (Haldane, 2015). Companies are falling for a quick fix via short-term returns in the form of dividends, rather than investing in longer-term productive projects which may not bear fruit for years.

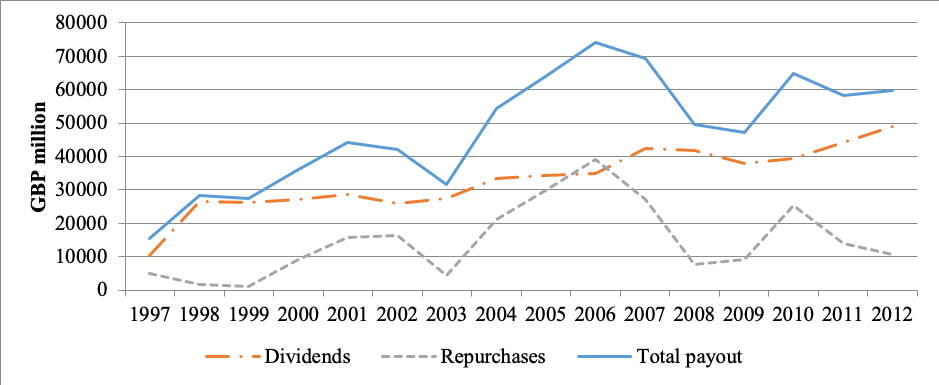

Figure 1. The evolution of dividends, share repurchases and total payout amounts for all UK firms 1997–2012

An extensive literature has been devoted to dividend payout in economies with highly developed capital markets because of its potential effects on investment, productivity and the long-term value of firms. Under financial constraints, if dividends are for some reason sticky downwards, investment may be cut – wholly or partially instead of dividends – when there is insufficient cash to pay dividends. In other words, investment decisions and dividend payout decisions are not independent.

Similar to what we observe with the current Covid-19 crisis, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial shock, cash-constrained firms planned to cut both investment and dividends by equal amounts and there was evidence that profitable investment may have been sacrificed in order to defend the payout (Campello, Graham and Harvey, 2010). Even before the financial crisis, senior corporate executives indicated in surveys that such a trade-off existed and less than 40% agreed that dividend decisions were made after the investment decisions (Brav, Graham, Harvey and Michaely, 2005). The same feature was observed in a long-term study of UK dividends throughout 1974-99, where it was noted that in adjusting to a balance sheet shock, real outcomes such as investment will suffer as dividends are protected (Benito and Young, 2003). These arguments highlight some contradictions to the agency theory which has traditionally been arguing for dividends as a tool for disciplining managers who would otherwise overinvest in unprofitable projects.

In an open-access publication (Ciaran, Grosman and Scaramozzino), we propose an alternative explanation to the one advanced by the agency theory, which we call investor pressure, and analyse three main channels of influence for investor pressure namely, pressure arising from acquisitions activity; pressure arising from stricter formal governance standards; and pressure through institutional short-term trading. We find that firms adopt a higher dividend payout to discourage takeover bids. We base our work on an extensive dataset of UK publicly listed firms in the period of 1997-2012.

Investor pressure arising from acquisitions activity

Previous literature (Lomax,1990; Dickerson, Gibson and Tsakalotos, 1998) has identified fear of takeover as an important factor pushing UK firms towards higher dividend payout. The threat of takeover can be assessed from the extent of acquisition activity at a given time in any given industry. Our results show a positive effect of payout for the acquisition activity, which is highly significant (1% level), confirming that this channel of investor influence on dividends exists.

Investor pressure and corporate governance

The UK corporate governance code – which was operative from the 1990s and put into statute as a combined code in 2000 – has strengthened a shareholder value orientation by firms, which may have resulted in a short-term focus that militates against cashflow retention and in favour of payout. Here we note the potential effects of two aspects of the code: an increased role for independent directors and equity-based pay for executives.

Independent directors have less detailed knowledge of the firm’s operations than executives but need to make a judgement between retention and payout of profits. This leads to a preference for transparent measures of performance rather than soft expectations of future cash-flows which require expert interpretation and is an enabler for more dividends. Short-termism may also be induced by an increased reliance on equity-based compensation where executives are incentivised not to challenge investor pressure due to their pay being linked to the current share price (Dhanani and Roberts, 2009; Brochet, Loumioti and Serafeim, 2015). Our results confirm the role of the two governance variables in increasing investor pressure, with both variables (proportion of independent directors and proportion of equity in total pay) being positively significant at the 5% level but only within the FTSE 100 firms. UK governance codes are of the “comply or explain” variety and are both more restrictive – and more complied with – by companies in the FTSE 100.

Investor pressure and investor trading behaviour

Firms’ concern with their share price becomes heightened when there is increased activity by short-term traders, and this may increase dividend payout. When this occurs – and share churn rises – the affected firms experience short-term market pressure and may become more receptive to pleasing investors with higher dividends. There is a particular form of high-frequency trading, swing trade, which is differentiated from the standard buy-and-hold pattern in that the asset is held for a short period of days before it is sold for an intended gain. Firms most vulnerable to swing trades will tend to defend their share price by the higher payout. Our results show that firm-years where there is a sudden increase in trading volume are characterised by higher dividends, significant at the 0.1% level. We also obtain significant results for swing trades.

Taken together, our results provide evidential support for a tilt away from agency theory in dividend research studies. We provide a unified framework for testing the consequences of investor pressure for dividend payout. Our work has suggested that investor pressure stemming from short-term horizons leads to excessive payout, and this suggests a research focus on the origin and transmission of short-termist pressure from investors and financial markets.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper “Dividend policy and investor pressure“, Economic Modelling, in press.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Erol Ahmed on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Ciaran Driver is a professor of economics at the School of Finance and Management, SOAS, and a member of the SOAS academic board. He co-edited Corporate Governance in Contention (OUP 2018). He is a fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences and a trustee of the New Economics Foundation.

Ciaran Driver is a professor of economics at the School of Finance and Management, SOAS, and a member of the SOAS academic board. He co-edited Corporate Governance in Contention (OUP 2018). He is a fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences and a trustee of the New Economics Foundation.

Anna Grosman is an associate professor (with tenure) in innovation and entrepreneurship at Loughborough University London. Her research falls at the intersection of corporate governance, corporate finance and international business, with a special emphasis on contemporary state capitalism, and corporate governance issues of state-affiliated organisations. She has a PhD from Imperial College, London.

Anna Grosman is an associate professor (with tenure) in innovation and entrepreneurship at Loughborough University London. Her research falls at the intersection of corporate governance, corporate finance and international business, with a special emphasis on contemporary state capitalism, and corporate governance issues of state-affiliated organisations. She has a PhD from Imperial College, London.

Pasquale Scaramozzino is a professor of economics at the School of Finance and Management, SOAS, and at University of Rome Tor Vergata. He has received a PhD in economics from LSE and has previously taught at the University of Bristol and at UCL.

Pasquale Scaramozzino is a professor of economics at the School of Finance and Management, SOAS, and at University of Rome Tor Vergata. He has received a PhD in economics from LSE and has previously taught at the University of Bristol and at UCL.