Management matters for explaining differentials in productivity between and within countries and sectors. Across countries, management practices – as measured in the World Management Survey (WMS) – explain on average around 30% of the gap in total factor productivity with the United States (Bloom et al, 2016); and experimental evidence from Indian textile plants supports a causal interpretation (Bloom et al, 2013).

In recognition of their importance, national statistics offices around the world are now embedding questions on management practices in their business surveys – for example the Management and Organizational Practices Survey conducted by the US Census Bureau; or the Management and Expectations Survey carried out by the UK’s Office for National Statistics. In addition, significant policy attention is being focused on trying to improve the performance of firms that are lagging in adopting best practices.

This is particularly the case in the UK, where management practices are on average worse than in other advanced economies – notably Germany and the United States – and where there is a larger tail of badly managed, low productivity firms. In recent years, the UK government has funded initiatives such as ‘Be the Business’, which aims to help firms improve their management practices and the Business Basics Fund, which seeks to test methods of supporting small businesses to adopt better management practices (and technologies more generally).

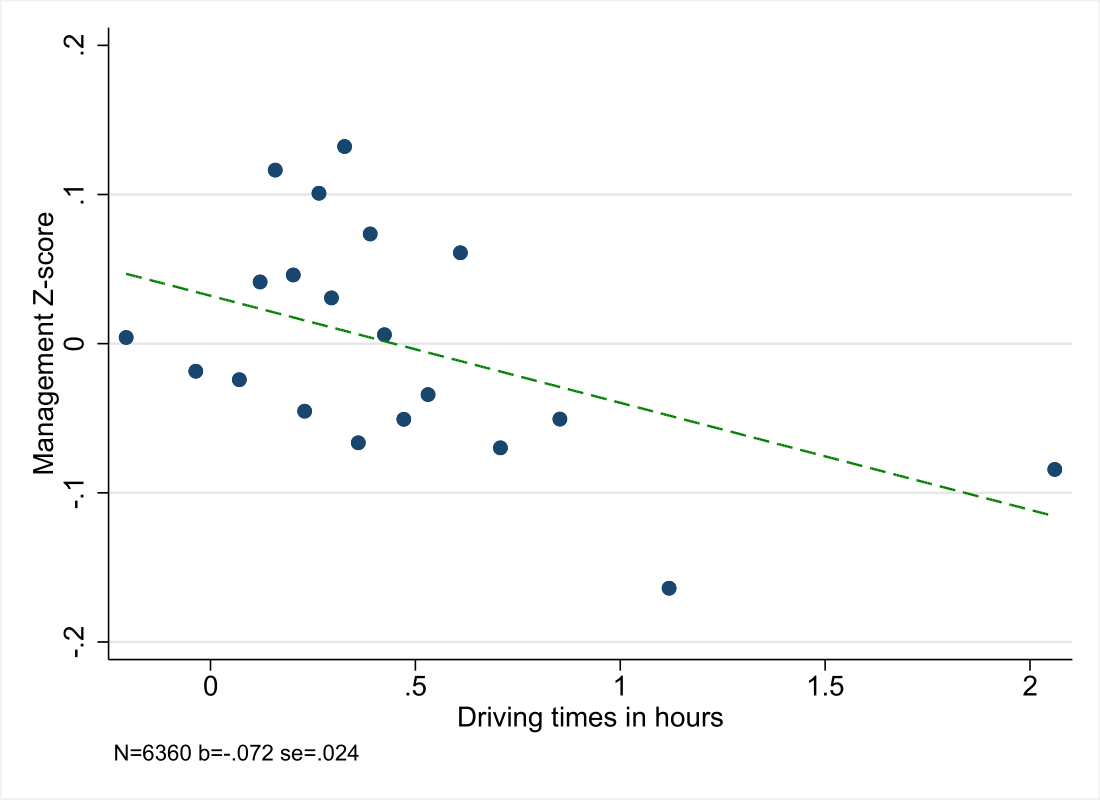

Given that management practices are so important for firm performance, and can be measured and benchmarked across firms, why do we not see all firms adopting best practice? As Figure 1 illustrates, the evidence suggests that skills could be important: the education levels of both managers and workers are strongly correlated with management scores (Bloom and Van Reenen, 2007, 2010; Bloom et al, 2014).

Figure 1. Firm skills and management practices

Notes: Scatter plot of average management Z-score on average 1n(1+ degree share) within 20 evenly sized bins. Variation is within country. The dashed line represents the line of best fit. Source: authors’ analysis of data from the WMS.

Our study contributes to this body of research by combining WMS data on management practices in small and medium-sized manufacturing firms with newly constructed data across 19 countries related to plant and region-level skill availability. To provide evidence for complementarities, we estimate ‘factor demand’ equations (Brynjolfsson and Milgrom, 2013), where the idea is that the demand for a factor increases as the price of a complementary factor falls. We find robust evidence that firms facing more abundant – and cheaper – skills have higher management scores.

Management-skill complementarity

We argue that this evidence supports the hypothesis that modern management practices and a skilled workforce are complementary. This is consistent with a skilled workforce increasing the marginal benefit or lowering the marginal cost associated with good management practices, so that firms facing a skill-abundant workforce employ more skilled labour and have better management practices. In this sense, good management practices are examples of ‘skill-biased management’.

A complementarity between worker skills and management practices may seem intuitive. The surveyed management practices closely resemble the complementary characteristics of ‘modern manufacturing’ discussed by Milgrom and Roberts (1990) and Roberts (1995). Highly skilled, cross-trained workers are listed alongside (among other things) lean production techniques, performance tracking and communications as features of the modern firm. An educated workforce is more likely to show initiative and be able to implement complex, flexible and decentralised production practices.

On the other hand, it could be argued that certain management practices and skilled workers could be substitutes. A firm with a highly skilled workforce might have less need for constant performance tracking and communicating – more able workers could just be left to get on with their jobs.

Shedding light on this issue empirically is therefore valuable for helping managers and policy-makers to understand best how to improve management practices and hence productivity.

Universities, skill premia and management practices

We construct a new dataset across 19 countries based on university location from the World Higher Education Database (Valero and Van Reenen, 2019) to create a measure of distance to the closest university; and skilled versus unskilled wages from international labour force surveys or administrative data across 13 countries.

We hypothesise that universities increase the supply of skills and hence reduce the price of skills – and that this is the mechanism through which we might expect the distance measure to be related to firm human capital and management practices. In support of this, we show that regions with higher university density have a higher degree share and a lower skill premium. This is a new finding that suggests that skills are expensive when they are relatively scarce in a location and cheap when abundant.

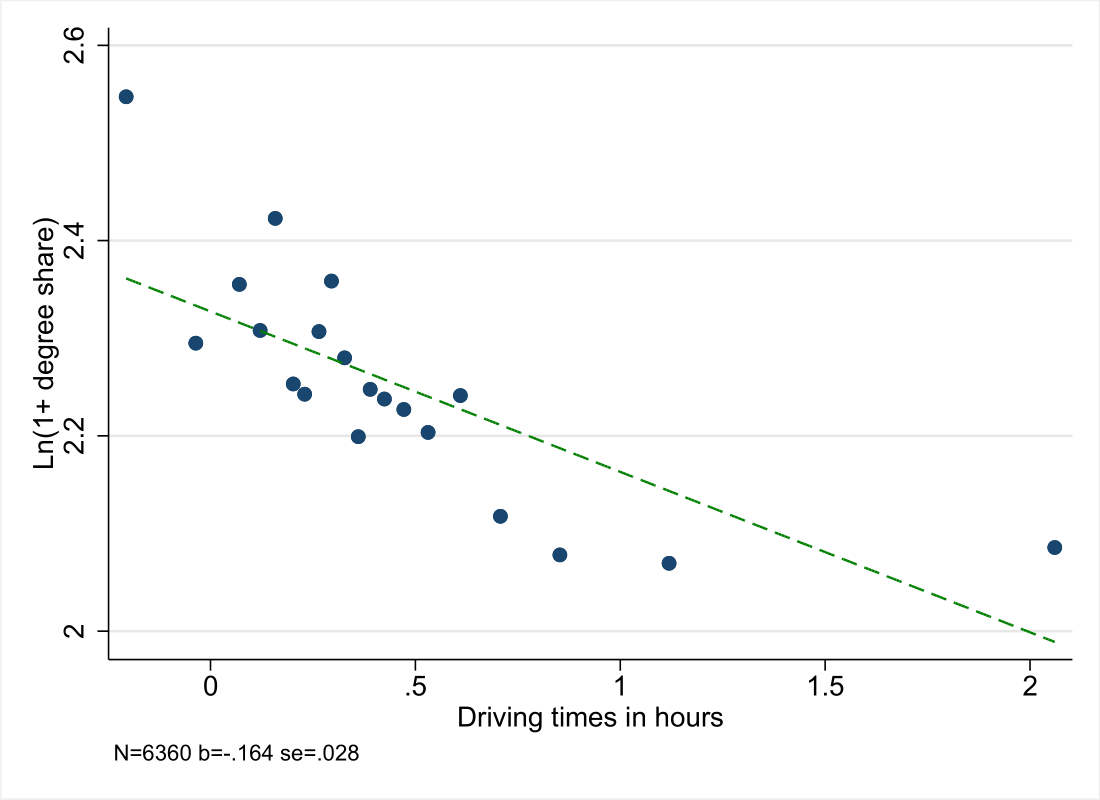

We find a negative relationship between drive time to the nearest university and firm-level human capital and management practices: firms further from universities have fewer skilled workers and managers, and are on average worse managed (see Figure 2). These relationships are robust to the inclusion of relevant controls (firm and geographic characteristics) and fixed effects (survey year, industry and region).

Figure 2. Distance to university, management scores and degree share

Notes: Scatter plot of average management Z-score (top) and 1n(1+ degree share) (bottom) on average travel time within 20 evenly sized bins. Variation is within country. The dashed line represents the line of best fit. Source: authors’ analysis of data from the WMS and World Higher Education Database.

Next, we replace distance to nearest university with the regional skill premium in our analysis, and show that firms facing higher skill premia in the region where they are located employ significantly less skilled workers and are significantly worse managed.

We find that these results are stronger when we exclude regions around capital cities, where we might expect demand shocks or other unobservables that raise both the skill premium and management practices to be more prevalent. Moreover, firms in capital cities are more likely to be able to recruit from wider areas (due to commuting patterns or inward migration).

We also find that the relationships between management practices and both university distance and regional skill premia are stronger for single-plant firms compared with plants that are part of multinationals or multi-plant domestic firms.

This is intuitive, since these types of firms are likely to be less reliant on the local environment when recruiting staff and setting management practices. Plants that are part of larger multinationals may be able to attract workers from other regions or countries due to their stronger brand, and might also move staff between locations. Moreover, management practices in such firms might be set centrally at the company headquarters, which may be in a different region or country.

We cannot rule out the possibility that our results are driven by better-managed firms choosing locations close to universities. But we partially address this concern by showing that there is no differential effect for firms that are founded after their nearest university, and by considering within-firm variation as an extension to the skill premium analysis.

Of course, it could be that universities are just educating better managers or providing consultancy services to local firms. If that were the case, we would expect the relationships between management practices and university proximity to be stronger for universities with business schools, but this is not evident in the data. We find no evidence of heterogeneity in our effects for universities offering different disciplines, including management, business or economics courses.

On a sub-sample of firms where performance data are available, we also go one step further to examine whether there is evidence that a skilled workforce is associated with good management practices because skills increase the marginal benefit of their adoption. This is tested using interactions between workforce skills and management practices.

We estimate simple production functions including firm degree share, and then external skills measures (distance to university and regional skill premium) and their interaction with management practices. Here we find more tentative evidence of complementarities in the case of single-plant firms only, which is consistent with the finding that plant-specific locational measures of skill supply appear more relevant in such cases.

Implications for industrial policy

Our finding that firms closer to universities have a more highly skilled workforce and better management practices is relevant for policy-makers seeking to maximise the positive impacts that universities have on their local firms and economies (Azmat et al, 2018).

More generally, the evidence that management and workforce skills are complementary implies that policies to raise human capital not only raise productivity via a direct impact on worker skills, but also via an indirect effect as firms with a skilled workforce are more likely to adopt better management practices.

In addition, it implies that the pay-offs from implementing policies to raise general human capital and policies specifically aimed at improving management practices (such as managerial training) are higher when such policies are implemented together.

An important question for future research is to understand what kinds of skills matter. The measure of firm-level human capital used in our study (degree share) does not account for skills acquired from vocational education or on-the-job training. Policy-makers need to understand better the specific types of skill that are relevant with respect to modern management practices, and how these can best be acquired.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post appeared first on CentrePiece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance. It is based on Skill-Biased Management: Evidence from Manufacturing Firms, The Economic Journal.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by James Losey, under a CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Andy Feng is at the Ministry of Trade and Industry, Government of Singapore. From 2010 to 2013 he was also a research assistant at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance.

Andy Feng is at the Ministry of Trade and Industry, Government of Singapore. From 2010 to 2013 he was also a research assistant at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance.

Anna Valero is an ESRC innovation fellow at the CEP. She received her PhD in economics at the LSE in 2018. Her research is focused on the drivers of productivity and innovation, and in particular the role of skills and universities in explaining differences in economic performance between firms and regions. Anna has also been working on UK productivity and industrial strategy more broadly, and in 2017 was a research director for the LSE Growth Commission. Previously, Anna was a manager at Deloitte’s Economic Consulting practice.

Anna Valero is an ESRC innovation fellow at the CEP. She received her PhD in economics at the LSE in 2018. Her research is focused on the drivers of productivity and innovation, and in particular the role of skills and universities in explaining differences in economic performance between firms and regions. Anna has also been working on UK productivity and industrial strategy more broadly, and in 2017 was a research director for the LSE Growth Commission. Previously, Anna was a manager at Deloitte’s Economic Consulting practice.