Today’s political and social campaigns rely on social media. Grassroots organisations use social media to stimulate public debate, build coalitions, mobilise people, and provide practical guidance to social movement activists. Labour unions in the United States and many other countries are realising the need to revitalise the traditional workplace model of unionism. Consequently, they are moving away from simply participating in social media conversations and using social media as a supplemental communication channel to connect their members. Now they are taking the lead in social media discussions, putting the labour rights of marginalised and oppressed workers at the forefront of policy-oriented advocacy campaigns.

Given the open debate and fierce competition in social media, however, only users who manage to become social media opinion leaders — that is, those who are able to affect the attitudes and behaviours of others online and beyond – can define a campaign’s goal and set the course of action. By achieving opinion leadership, unions can provide a coherent framework for a labour rights advocacy campaign.

We explored if, how and why unions can become social media opinion leaders by looking at the Fight for $15 campaign (FF$15). Civil society organisations (CSOs), individual supporters, and unions came together to make claims for a $15 minimum wage across the USA since 2012.. The campaign expanded into Canada and internationally. As a result of the broad support and activism, a gradual increase in the minimum wage to $15 per hour was approved in almost 40 US cities.

We focused on FF$15 because this was a very effective US labour rights campaign. What were the unions’ patterns of action on Twitter? How active were they in Twitter dialogues? Did they produce original meanings (tweeting) or did they simply endorse meanings created by other participants (retweeting)? What kinds of content did they post? Were trade unions opinion leaders in the FF$15 Twitter debate?

One of the key reasons for success was the use of social media to build support among diverse actors (unions, CSOs, individual supporters), consolidate meanings around the campaign, create a collective identity, and promote actions and achievements

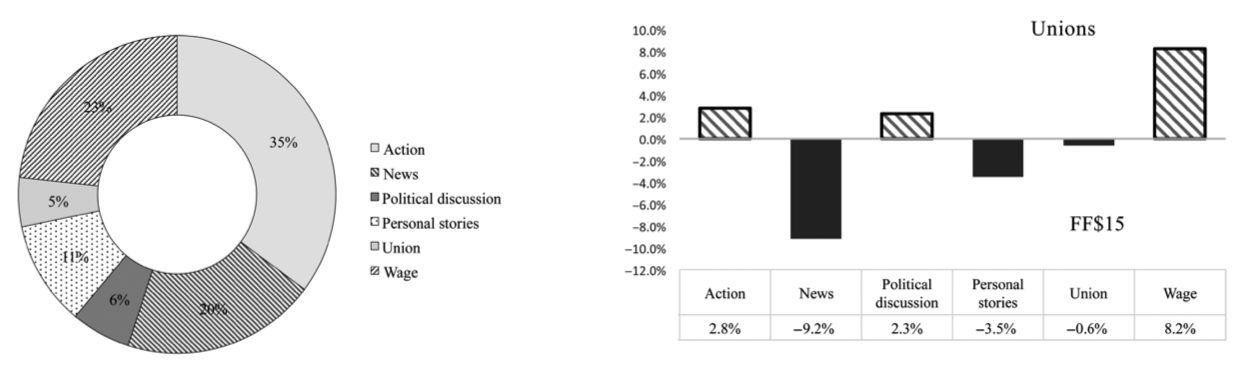

We looked at unions’ patterns of communication, endorsement, and posted content on social media in the context of the FF$15 Twitter campaign to see if they were able to emerge as opinion leaders. While, in theory, they were talking about the same thing, labour union accounts behaved very differently from the FF$15 accounts generally considered to be the face of the movement. Labour union Twitter accounts focused on topics such as political discussion, strike actions, and wages, while the FF$15 accounts discussed more personal stories of low wage workers and campaign-related news. Labour unions also tweeted original messages more often than they retweeted others’ postings.

We interviewed social media communication experts from trade unions and FF$15 groups to understand the behaviours of social media communication. On the one hand, FF$15 accounts strategically and carefully crafted compelling messages of the “voice of working Americans” to attract social media attention, create emotional tension and build a supportive constituency to advocate for desired changes on minimum wage. On the other hand, labour unions considered communication in social media as supplementary to traditional trade union face-to-face organising. Social media seemed useful only to inform union members. Unions’ social media communication style was mostly ‘one-way’, institutionally-bound, slow to react and introduce news, and limited in relationship-building. Union tweets were the outcome of a ‘carefully decided’ communication strategy, often after a long democratic discussion, part of a ‘delicate political balancing act that [unions] are trying to play internally and externally’. Finally, the posted content suffered from a lack of coordination across organisational levels because social media skills varied. In short, unions were not leaders in the FF$15 Twitter campaign.

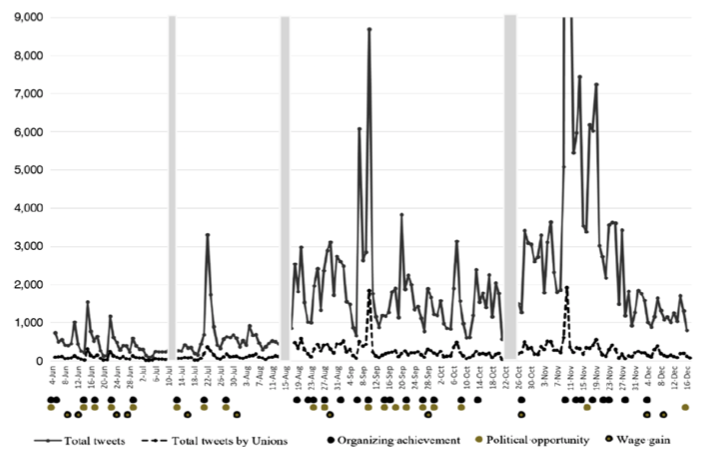

Figure 1. Volume of daily FF$15 tweets June – December, 2015

Notes: The grey areas represent eight days during the observational period when we were unable to conduct real-time Twitter data fetching, due to a technical glitch. The volume was capped on November 10, 2015, when 41,274 FF$15 tweets were posted.

Figure 2. Content analysis of a tweet sample by unions and FF$15 groups

Interestingly, although unions’ social media behaviours undermined their ability to be main contributors to the FF$15 debate, and they lost the opportunity to leverage a large supportive network within the core FF$15 community, the average Twitter users saw labour unions as opinion leaders, able to talk with authority about $15 dollar minimum wages. In the eyes of the public, trade unions had an established reputation as an institution devoted to defending labour rights and wages and, as such, could be trusted.

Admittedly, this was a mitigated leadership: unions only leveraged their core supporting offline “traditional” networks, such as united and powerful members, and institutional relationships spanning different union organisational levels. Support for unions posed serious challenges. First, offline membership activism represented a marginal share of members. Second, union support based on internal union endorsement at national, state, and local organisational levels was important, but it suffered from particularism and lack of alignment. Finally, and more importantly, achieving opinion leadership without nurturing relationships beyond union offline institutional links inflated the risk of union isolation and parochialism. Social media can easily amplify negative events and push users to distrust an institution. Support may be ephemeral.

To become active players on social media, unions should develop a social media communication strategy able to reach out to and consolidate a wider range of online supporters beyond members and well-known users. We propose three strategies.

First, unions could leverage the consolidated offline relationships of their core supporters with non-union people to enlarge their online supportive network and so increase their online endorsement. Local unions could supervise and coordinate such arms-length online relationships, providing more visibility to their new supporters through reciprocal actions, such as retweeting their messages.

Second, unions could develop a clear strategy for selecting unknown social media supporters. Monitoring unknown supporters’ patterns of action, posted content, and network characteristics, making efforts to reach out to them and nurturing the relationship through reciprocity could increase the number of core social media union supporters.

Third, these two strategies could be nested in a union social media communication policy aimed at improving union internal consistency and vertical integration across organisational levels. Coupling stronger vertical communication integration with an arms-length support of and a nurturing relationship with selected unknown supporters might allow unions to substantially increase their supportive network across internal and external (non-union) supporters and across scales (local, regional, national, international). The ensuing synergy may allow unions to take full advantage of social media’s potential and permit them to achieve and maintain leadership in social media labour rights campaigns targeting low-wage and unrepresented workers, while protecting themselves from backlash and a possible erosion of their institutional reputation.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on “Tweeting and Retweeting for Fight for $15: Unions as Dinosaur Opinion Leaders?“, British Journal of Industrial Relations.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Jurriaan Persyn, under a CC-BY-NC-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Lorenzo Frangi is a professor of employment relations in the department of organisation and human resources, School of Management Sciences (ESG), at the University of Quebec, Montreal (UQAM).

Lorenzo Frangi is a professor of employment relations in the department of organisation and human resources, School of Management Sciences (ESG), at the University of Quebec, Montreal (UQAM).

Tingting Zhang is an assistant professor of management at Merrimack College. She has a PhD in industrial relations and human resources from the University of Toronto.

Tingting Zhang is an assistant professor of management at Merrimack College. She has a PhD in industrial relations and human resources from the University of Toronto.

Robert Hebdon is professor emeritus of industrial relations and organisational behaviour at McGill University’s Desautels Faculty of Management.

Robert Hebdon is professor emeritus of industrial relations and organisational behaviour at McGill University’s Desautels Faculty of Management.