It has become increasingly salient that publicly funded health care providers such as hospital are sensitive to incentives. There is increasing evidence that competition between health care providers produces efficiency and quality improvements (Gaynor and Propper, 2010), even when in some countries it has not produced the expected outcomes (Gobillon and Milcent, 2017). However, when health care providers compete with each other, coordination and information is left to market forces, via patients’ ability to choose the best provider, either public or private.This raises concerns during a pandemic, when swift decision-making reaching all health providers is so crucial.

Covid-19 pandemic as a coordination experiment

The management of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe has become a test for how agile the systems of managed competition are coordinating needs in the event of a health emergency, and more specifically in delivering the decision that benefits patients in a swift manner. In a recent article, we suggest that organisation models that lack an integrated authority might not be able to manage coordination, which results in delayed responses and higher fatalities, when timely health service reaction is key (Mak et al. 2020). This is especially true for coordination among services (primary care, hospital services, and home care).

When authority is integrated, regulators, which are used to managing competition, are better equipped to purchase personal protective equipment (PPE), manage the supply of hospital beds, and coordinate with other social services (e.g., transfers in and out of nursing homes). Networks with an integrated authority can reduce the risks of local shortages of PPE, identify and react to infected hospitals, e.g., by devoting some facilities to the emergency while leaving other hospitals free to carry on with normal hospital treatments.

Evidence from Italy

Possibly, one of the most illustrative cases of the effects of governance on the management of the pandemic is Italy, a country severely affected by COVID-19. To date, the number of official Italian contagions has risen to about 275,000 cases and 35,550 deaths. Since 1992, health care is regionally decentralised, i.e. different regions can make decisions around the organisation of inpatient and primary care. Particularly illustrative is the evidence from the three regions most severely hit at the beginning of the pandemic, namely Emilia Romagna, Veneto and Lombardy, which have chosen different models of managed competition.

Emilia Romagna adopted a model based on health care integration whereby public hospitals are in integrated networks, and the intensity of use of private providers is determined by the regional authority, which sets quality goals. About half of all beds are under the control of the regional health service. In contrast, Veneto has implemented a model of limited managed competition in the form of an internal market. Patients can choose among public and private providers with the presence of an integrated authority that controls the management of public hospitals. About two third of beds are under the control of the regional health service. This has limited shortages and allowed the closure of hospitals when needed.

Lombardy, unlike other regions, has adopted a disintegrated managed competition model based on an unambiguous separation between purchasing and providing functions, public hospitals have been transformed into autonomous organisations to compete with private providers. This means that no single bed is under the control of the regional health authority, which merely defines the general goals and controls its implementation. However, during a pandemic, regional authorities face coordination failures, and unnecessary delays in the information sharing between hospitals in the networks and the regional authority.

Lombardy was more severely hit than any other Italian regions; some recent evidence (Cereda et al. 2020) shows that the virus was around in the region as early as mid-January; the genetic sequence of the virus that spread in Codogno is different from the one in Bergamo, i.e., the region was hit on several fronts at the same time. However, COVID-19 related-hospital fatalities in Lombardy have been about twice the sum of Emilia Romagna and Veneto. The integration between hospitals and other services has been sometimes problematic, especially as concerns the nursing homes (Berloto, S., Notarnicola, E., Perobelli, E., Rotolo 2020) and emergency care (Garrafa et al. 2020, “When Fear Backfires: Emergency Department Accesses during the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Mimeo) and some of the problems may have been exacerbated by the governance model.

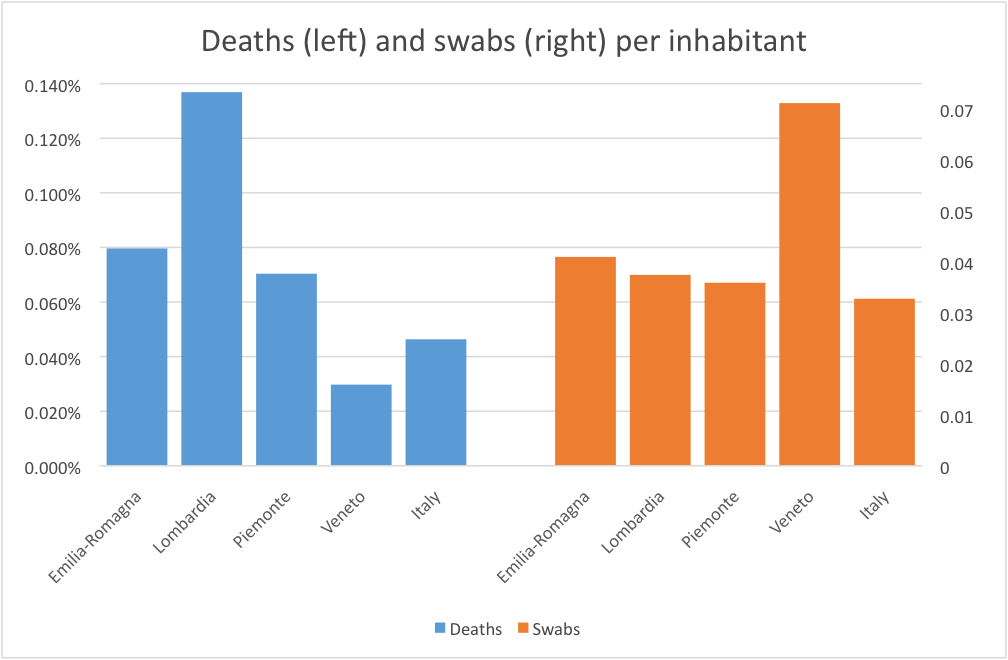

Figure 1 shows the number of deaths and swabs that were performed in the four most-hit regions in Italy in March and April 2020. Lombardy appears to be the region with the largest death rate per inhabitant. This result is even most striking when observing that the share of the elderly, the group most hit by the virus, is largely comparable across the three regions. Although the region was more severely hit and was likely to be the epicentre of the pandemic, the difference calls for more research into this matter.

Figure one. Deaths (left) and swabs (right) per inhabitant, selected regions

What type of managed competition works best?

The Italian experience suggests that decentralised managed competition does not seem to be the most effective model to manage a pandemic event. However, this system seems to be quite effective in improving quality and reducing heterogeneity among providers during normal times (Levaggi, Martini, and Spinelli, “Do Patients Elect Reference Hospitals? Evidence from Three Italian Regional Health Systems.” Mimeo 2020). If pandemics are a test of which models of managed competition we should adopt, an integrated model seem to provide a swifter reaction by minimising coordination efforts and information costs. However, in view of the trade-off that seems to emerge, there is scope for creative health care governance design that combines integration and decentralised managed competition.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Resilient Managed Competition during Pandemics: Lessons from the Italian experience during COVID-19, in Health Economics, Policy and Law, September 2020.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by rottonara, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Joan Costa-Font is an associate professor (reader) at LSE’s department of health policy. He is an economist affiliated with CESIfo in Munich and IZA, Bonn. The core of his current research focuses on health economics.

Joan Costa-Font is an associate professor (reader) at LSE’s department of health policy. He is an economist affiliated with CESIfo in Munich and IZA, Bonn. The core of his current research focuses on health economics.

Rosella Levaggi is a professor of economics and management at Università degli Studi di Brescia (UNIBS), Italy.

Rosella Levaggi is a professor of economics and management at Università degli Studi di Brescia (UNIBS), Italy.

Gilberto Turati is a professor of public finance at Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore. He is the current director of the two-year healthcare management programme at Università Cattolica in Rome. For several years, he was programme director of the master’s in economics and health policy of Coripe Piemonte and the University of Turin.

Gilberto Turati is a professor of public finance at Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore. He is the current director of the two-year healthcare management programme at Università Cattolica in Rome. For several years, he was programme director of the master’s in economics and health policy of Coripe Piemonte and the University of Turin.