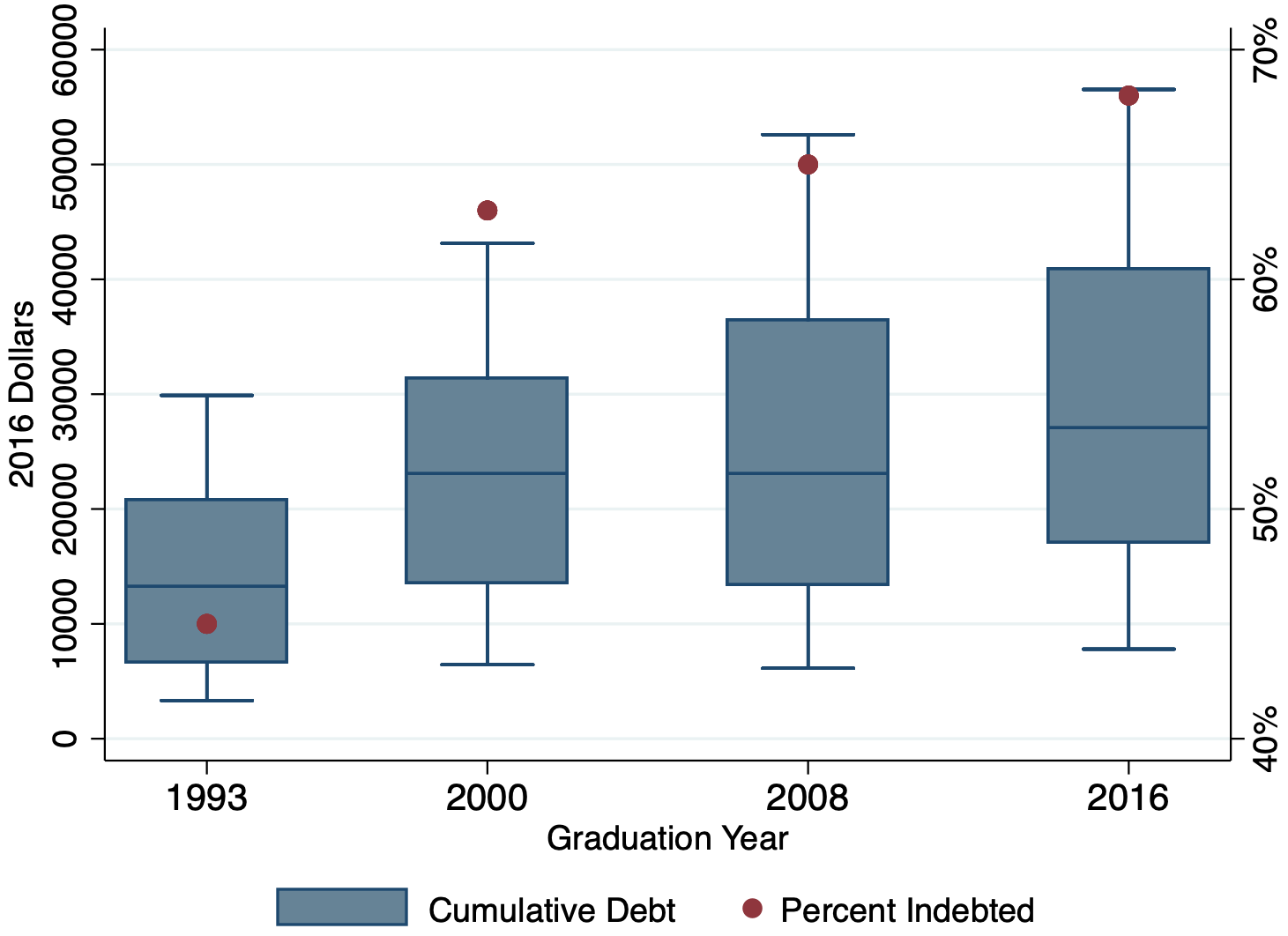

Student loans have become the new normal for bachelor’s degree recipients in the United States. Between 1993 and 2016, the percentage of students who had borrowed at any time during their undergraduate years rose from 45 percent for 1993 graduates to 68 percent for 2016 graduates (Figure 1). Among borrowers, the median cumulative amount borrowed rose from $13,000 to $27,000 in real terms, with 25% of graduating seniors having borrowed more than $40,000 in 2016.

Figure 1. Evolution of percentage and amount borrowed for undergraduate education

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 1993/94, 2000/01, 2007/08 and 2015/16 Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study (B&B:93/94, B&B:2000/01, B&B:2007/08, B&B:2015/16).

In our working paper, we use data from the Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study (B&B) to investigate how increased borrowing has shaped career, education and housing choices for young Americans.

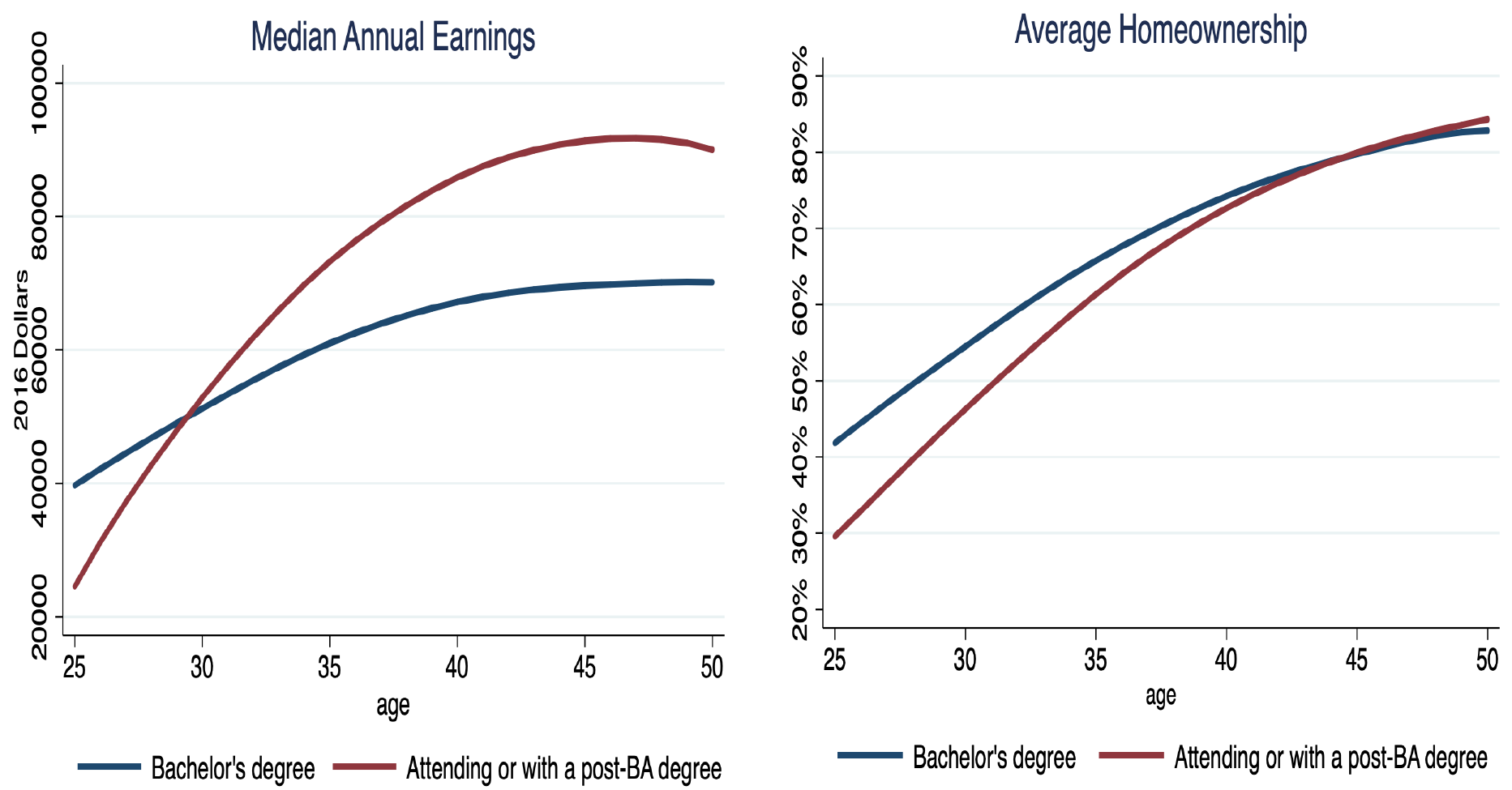

Figure 2 shows the median annual earnings and average homeownership for college graduates by educational attainment and age. Graduates face an important trade-off: investing in long-term earning potential through additional human capital versus starting off with higher earnings and being able to pay off debts. We want to understand if student debt affects this trade-off in a significant way, and how housing choices interact with it.

Figure 2. Earnings and homeownership by educational attainment and age

Source: Current Population Survey (CPS, 2013-2019) – males with at least a bachelor’s degree.

In order to empirically examine how borrowing affects post-bachelor choices, we need to overcome the problem that the amount borrowed may be determined by unobserved students’ characteristics. We address this problem by introducing an instrument based on variations in colleges’ financial aid. We then use these yearly changes in aid to extract variation in borrowing that is not correlated with post-bachelor choices through unobserved characteristics.

We find that undergraduate debt induces graduates to front load earnings: on average, increasing debt balances by 10% has an effect of increasing earnings one year after graduation by 2.9%. The same graduates would see an average fall of 1.02% in their yearly earnings growth during the following years.

Three channels contribute to this result. First, indebted students make on average different occupational choices. Occupations are classified as ‘steep’ careers if they are in the top quintile of earnings growth between age 25-30 and age 45-50. As debt balances grow, their likelihood to choose that occupation decreases.

Second, increasing debt balances has a negative effect on post-bachelor’s degree attendance and completion. This is relevant, as attending graduate studies is the primary gateway to access a range of occupations with higher earnings growth potential.

The third channel is less intuitive. Our empirical estimates show that more indebted graduates tend to access homeownership relatively earlier. How is this possible? The crucial factor is that both housing and career choices are inherently discrete.

To understand this channel, suppose workers could only choose in a binary fashion between doing graduate school or not, and between buying a house or not. As we show in a simple model, there is a large region of debt values for which increasing balances induces workers to give up graduate school and stop being a renter – that is, debt decreases graduate school attendance but increases home ownership. The same simple theoretical model can then be used to show that, as individuals become homeowners, they are less likely to switch careers or attend graduate school – and this is the third channel at play.

We then discuss the career – housing trade-off through the workings of a richer life cycle model, estimated on aggregate US data. The model highlights two important facts:

- Non-monetary returns to investment in housing and education are large, and important in explaining observed behaviour: were housing choices not valuable to graduates, the effects of student debt on their career choices would be significantly smaller.

- The role played by debt in affecting subsequent choices crucially stems from the rigidity of the standard repayment schedule

To this end, we compare the effects of different types of education finance policy. Income-based repayment plans and broader debt forgiveness plans emphasise reducing the impact of debt on choices made soon after graduation. The two types of policy have similar effects, in spite of the difference for the government’s budget: they increase enrolment in post-bachelor programs and in careers with higher earnings growth. In short, they allow borrowers to forego high immediate earnings and instead invest in their earning potential.

Interestingly, these policies also affect the average age of entry into home ownership- but by bringing it up instead of down. This delay in home ownership shows that selection into a career or education channel is more impactful than immediate financial relief offered by cancelled or postponed payments.

Our paper shows how student debt exacerbates the trade-off between housing and human capital investment and leads graduates to search for higher wages, at the expense of future growth. It is important to highlight the normative analysis of education financing policies – the debate on student loans needs to focus on how young workers are affected in practice by having to make certain payments after college graduation.

Authors’ disclaimer: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ presentation at the European Economic Association’s annual congress, August 2020.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by tadhanna, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Marc Folch is a PhD candidate in economics from the University of Pennsylvania. His research interests are macroeconomics, labour economics and the economics of education.

Marc Folch is a PhD candidate in economics from the University of Pennsylvania. His research interests are macroeconomics, labour economics and the economics of education.

Luca Mazzone is an economist at the fiscal affairs department of the International Monetary Fund and has a PhD from the University of Zurich and the Swiss Finance Institute.

Luca Mazzone is an economist at the fiscal affairs department of the International Monetary Fund and has a PhD from the University of Zurich and the Swiss Finance Institute.