In its quest to fight the health implications brought by obesity, the UK government announced on 27 July that England will be banning “buy one get one free” (BOGOF) deal promotions on unhealthy food, as well as junk food adverts before 9 pm for the entire UK. In addition, it will hold two consultations, one on whether to stop fast food adverts online altogether and another on alcoholic drinks, and will introduce new rules for displaying calories on menus, which will apply to any restaurant, cafe or takeaway chain with more than 250 employees (BBC News, 2020).

Elsewhere in the UK, similar measures were considered by the Scottish government as part of its 2018 Diet and Healthy Weight Delivery Plan, which aimed at halving childhood obesity by 2030 and significantly reducing diet-related health inequalities. However, on 11 June the Scottish government announced that it was putting the legislation on hold and was no longer planning to introduce the Restricting Foods Promotions Bill in 2020 due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the food and drink and retail industries and on consumer behaviour (The Scottish Parliament, 2020).

Although everyone agrees that obesity is a serious health problem, which requires an urgent solution, the reactions to the UK government announcement were all over the spectrum. On the one hand, the Food and Drink Federation criticised the measures pointing out that new restrictions on promoting and advertising everyday food and drink will increase the price of food, reduce consumer choice and threaten jobs across the UK, just to save 1.7 calories a day. Similarly, the Advertising Association considered them “extreme” and “unnecessary” measures that would have little effect in reducing obesity (Food Navigator, 2020). On the other side of the spectrum were health and nutrition campaigners such as Action on Sugar and Action on Salt and Public Health England (PHE), who were delighted with the plans, which were found ambitious and on the right direction to tackle obesity, though they considered that the plans missed to mention continuation of the reformulation campaign.

The purpose of this piece is to provide information focusing on the use of promotions using figures for Scotland (note that UK retailers operate a country-wide policy). The figures are on discretionary foods (FSS, 2018), which is the term introduced by Food Standards Scotland (FSS) in 2015 and that agencies such as PHE and FSS have been using instead of the more media-oriented label “junk food”.

The foods identified as discretionary by the FSS were confectionery, sweet biscuits, savoury snacks, cakes, pastries, puddings, and sugared soft drinks. These foods have a significant impact on diet, accounting for, on average, about one fifth of total calories, total fat, and saturated fats and over half of daily free sugars (i.e., added sugar) consumption. These foods are optional in the diet and therefore are considered discretionary (FSS, 2018).

The use of promotions on discretionary foods

Promotions are used for different purposes in food marketing (e.g., to increase sales of a product, encourage the reduction of stock, promote the introduction of new products). They have been found to have a positive effect on food purchases (Revoredo-Giha et al., 2015).

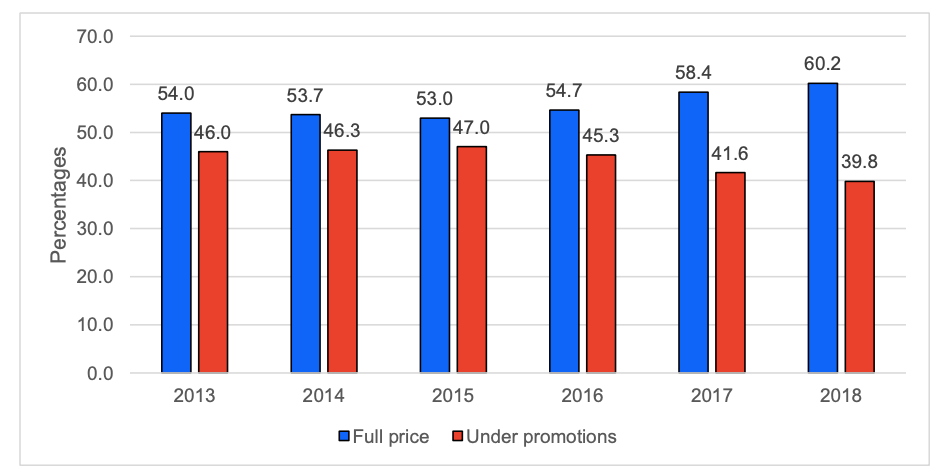

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the share of products sold at full price (i.e., without promotion) and under some promotion. The data indicate that using promotions for discretionary foods is a decreasing trend, accounting for around 40% of the total; meanwhile, an increasing proportion of the products are sold at full price.

Figure 1. Discretionary foods – evolution of use of promotions (% of total category value)

Source: Own elaboration based on Kantar Worldpanel for Scotland

There isn’t only one type of promotion. The most common are: temporary price reductions (TPR), e.g., 10% off; multibuy (which offers discounts for the bulk purchase of a product); Y for £X promotions (offering a set number of products for a set price, e.g., 2 for £2); and other promotions (e.g., extra free deals, meal deals, free gifts and samples) (FSS, 2018).

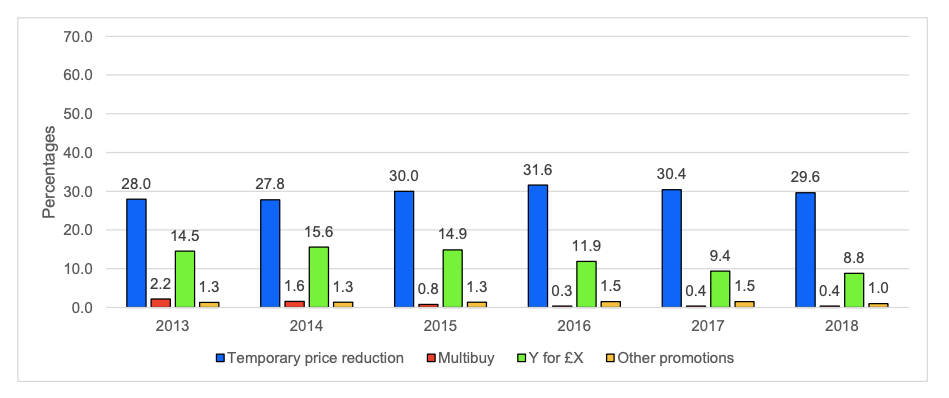

Figure 2 indicates how important multibuys are on the total purchases of discretionary foods categories. They have followed a decreasing trend: whilst in 2013 they accounted for 2.2% of sales, their share of sales in 2018 was 0.4%. Sometimes, the term multibuys is also applied to Y for £X promotions; this type, which is more significant, has also followed a decreasing trend, reaching about 9% in 2018.

The figure also shows that the most important promotion are temporary price reductions, which remained around 30% of discretionary food sales in the period 2013-2018, without any decreasing trend as in the case of the other promotions. As food demand reacts positively to the decrease of prices (e.g., Revoredo-Giha et al., 2015), TPRs have a significant effect on sales.

Figure 2. Discretionary foods – How important are multibuy promotions? (% of total category value)

Source: Own elaboration based on Kantar Worldpanel for Scotland

Source: Own elaboration based on Kantar Worldpanel for Scotland

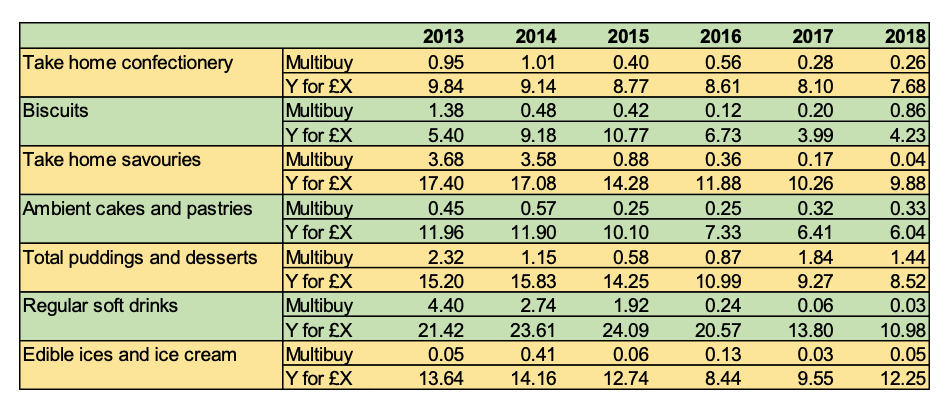

Promotion usage changes by product category. Table 1 shows that multibuys and Y for £X are not used in the same way for all the discretionary foods. When put together, they range between 5% and 12% of the categories’ sales. In addition, it is clear that Y for £X is the most important of the two types, and it has shown a decreasing trend (with the exception of edible ices and ice creams). In the case of regular soft drinks, Y for £X went from 24% in 2015 to 11% of total discretionary food sales in 2018.

Table 1. Are multibuys the same for all the discretionary products? (% of total category value)

Source: Own elaboration based on Kantar Worldpanel for Scotland

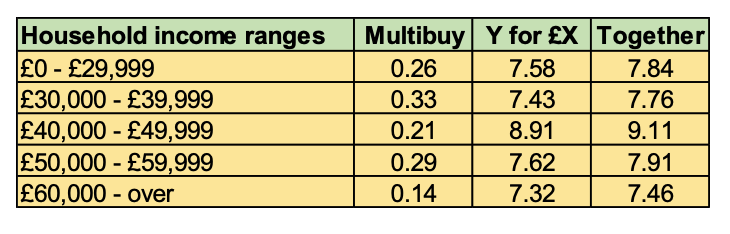

One point that has been made is that the elimination of buy-one-get-one-free deals would affect particularly low-income households. This, of course, as shown in Table 1, is product-specific, and cannot be generalised. Table 2 shows the example of take-home confectionery. The differences within groups are relatively minor, with the highest proportion of sales under the two types of promotion being on the £40,000 to £49,000 income range.

Table 2. Take home confectionery: How biased are multibuys against low income households? (% of total group purchases)

Source: Own elaboration based on Kantar Worldpanel for Scotland

What to expect of buy-one-get-one-free elimination?

It has been recognised that there’s no silver bullet in the fight against obesity and the food environment is complex. The banning of buy-one-get-one-free promotions alone will probably bring only a modest impact on the purchase and consumption of discretionary products, given their importance on the sales. Nevertheless, it is a movement in the right direction, addressing the incentives that consumers face when making food choices.

Since the nutritional quality of the food supply needs to be improved, the reformulation campaign must proceed. This requires collaboration between government and industry to set targets that are realistic and reachable.

Finally, it cannot be forgotten that without consumers embracing better dietary patterns, none of the considered measures will have any impact. This implies that consumers must be supported with information and other measures, which are probably more personalised.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Mike Mozart, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Cesar Revoredo is a senior economist and food marketing research team leader, and a reader in food supply chain economics at Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC).

Cesar Revoredo is a senior economist and food marketing research team leader, and a reader in food supply chain economics at Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC).