The regulatory changes introduced after the 2007-08 global financial crisis require banks to have contingency plans in case of distress. However, it is still not clear how such plans could be effective in resolving banks’ problems and mitigating systemic risk. The COVID-19 crisis and the drastic policy response that followed has produced an army of companies limping along in the twilight between the living and the dead. Many firms face cash flow and/or solvency difficulties at a scale unseen before. There are rising concerns regarding rapidly accumulating amounts of non-performing loans (NPLs) on banks’ balance sheets. Banks are under pressure to submit a contingency proposition to regulators in which they propose their recovery plan. Unfortunately, they need to prepare for such a ‘birthday’ with an imperfect plan.

Despite significant progress already made in formulating bank resolution objectives, many concerns remain as to whether the new mechanisms will work effectively during the “next” financial distress episodes. More importantly, it is not clear how they operate in the event of a crisis of a systemic nature. Although bank bailouts are seen as “dead tools” due to their moral hazard incentives as well as high budgetary costs, many scholars argue that early and timely government intervention was extremely important for limiting both the contagious effects of a crisis and its subsequent repercussions (e.g., Berger et al., 2020). Moreover, government has also played an important role in stimulating bank lending or NPLs restructuring (e.g., Berger and Roman, 2015; Homar, 2016). Thus, policymakers and regulators wonder whether bank bail-ins and redirecting bank resolution to bank managers and other creditors will indeed be more effective than the use of bailouts and under what circumstances.

The requisite scepticism centres around four key issues. First, redirecting banks’ problematic asset to the private investors might be difficult given high market uncertainty, limited market liquidity, and inconsistencies in asset valuation, which generally accompany financial crises, not to mention the adverse systemic events when equity markets are extremely thin. Second, the resolution of NPLs, especially when the losses are redirected to the creditors and the management generates moral hazard issues with respect to incentives to conduct effective resolution (particularly in the absence of any associated penalties) might lead to managerial forbearance, and thus delay banks’ recovery. Third, the amount of support offered by the creditors by redirecting the losses might be inadequate as contrasted to the typical bailout mechanism. Consequently, we might expect a slower recovery and limited credit extension from the banking sector. Finally, given the aforementioned reservations it is questionable to assume that available new resolution mechanisms will have a material effect on systemic risk mitigation.

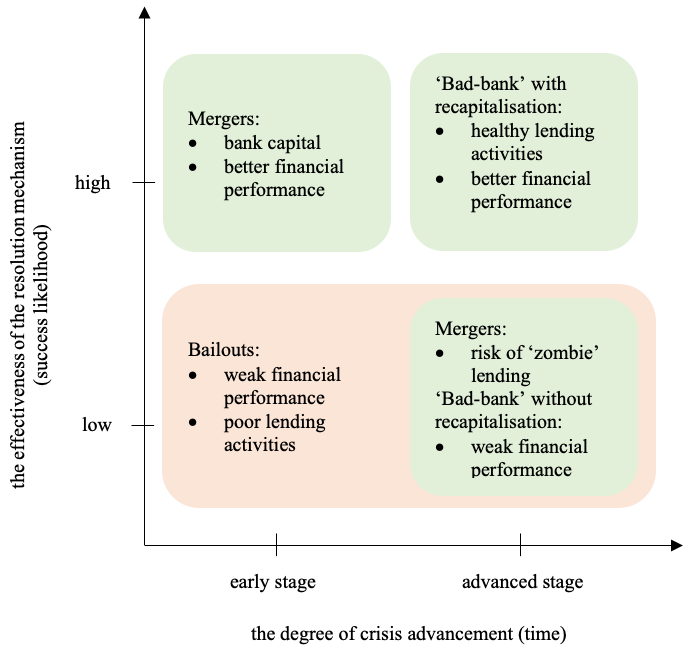

In our new paper, we analyse the effectiveness of selected resolution mechanisms with respect to the banking sector recovery and its systemic risk implications. We use a novel dataset of banks, which has been subject to resolution mechanisms during episodes of systemic events and compare them to those that were not under any resolution. We compare our results with financial institutions that were bailed out during the same period. Our sample covers 39 systemic banking crises during the period of 1992-2017. Figure 1 summarises our results on the spectrum of the success likelihood (i.e., measurers of bank financial performance) of the studied resolution mechanisms (y-axis) and the severity of the crisis during which these interventions occurred (x-axis).

Figure 1. The trade-offs between the success of bank resolution mechanisms and the degree of crisis severity

Source: Authors (2020)

Our results suggest that current bank resolution mechanisms can be effective in addressing only idiosyncratic risk. However, in case of severe crises they should be accompanied by sufficient recapitalisation. We argue that “one-policy fits all” does not hold. More specifically, we notice that in the early stages of the crisis, mergers are effective in resolving distressed banks without any additional financial support. However, in the event of a severe financial crisis, the creation of a “bad bank” needs to be accompanied by sufficient recapitalisation. Only then do we notice an improvement in bank performance as well as a formidable restoration of bank activity. We argue that pure restructuring under a “bad-bank” mechanism is not sufficient to restore bank’s health (i.e., advanced stage/low success spectrum in Figure 1). The lack of sufficient capital discourages banks from undertaking substantive restructuring and declaring their actual losses, possibly due to negative market reactions. At the same time pure recapitalisation without any restructuring procedures does not help either. More importantly, we claim that bailouts do not seem to address either systemic or banks’ idiosyncratic risks in an efficient way. Our results strongly encourage policymakers to speed up their work on resolution mechanisms that aim at mitigating systemic risk.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ 2020 working paper “New bank resolution mechanisms: Is it the end of the bailout era?”.

- The post expresses the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review, the London School of Economics or EBRD.

- Featured image by Christian Wiediger on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Aneta Hryckiewicz is a professor at Kozminski University in Warsaw.

Aneta Hryckiewicz is a professor at Kozminski University in Warsaw.

Natalia Kryg is a senior associate at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in London.

Natalia Kryg is a senior associate at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in London.

Dimitrios P. Tsomocos is a professor of Financial Economics and fellow in Management at Saïd Business School and St. Edmund Hall, University of Oxford.

Dimitrios P. Tsomocos is a professor of Financial Economics and fellow in Management at Saïd Business School and St. Edmund Hall, University of Oxford.