Flexible working is an ambivalent experience far exceeding the set of approved flexible work arrangements and practices enshrined in formal HR policies. On the one hand, employees experience flexibility as a perk that grants them agency to manage work responsibilities autonomously. But, as Almudena Cañibano argues, experiences of flexible working also include being available outside work hours, working overtime, or working wherever you are. She writes that since flexible working creates ambivalence, a growing literature suggests it should be understood as a paradox.

The advantages of flexible working have been advocated by international institutions, national governments, professional, managerial, and employee organisations alike. Flexible working has been a steadily growing phenomenon for decades, with increasing numbers of people working remotely and during hours other than the nine-to-five norm. For instance, the part of the British labour force working mainly from home has grown by 80% in twenty years (CIPD, 2020). Regular telecommuting in the United States grew by 115% between 2005-2015 (Dey et al., 2020). In northern European countries, for example Sweden, part-time homeworkers have tripled between 1999 and 2012 (Vilhelmson & Thulin, 2016). EU data indicates that workers with flexible working time arrangements increased from 24% in 2010 to 28% in 2015 (EWCS, 2015).

The pandemic has brought this slow but steady growth to a whole different level. Countries that were somewhat lagging behind such as Spain or Italy< in which less than 5% of workers could work from home, reached 32% and 45% respectively in April 2020. The 2020 wave of the European Working Conditions Survey is expected to depict a transformative picture in relation to 2015: under our 2020 predicament, flexible working was not a choice anymore.

There is no doubt that organizations are reinventing the way work is conducted. However, there is still much to be learned about what flexible working means for individuals. Now more than ever, exploring workers’ experiences of flexible working has become essential to understanding how work influences people’s lives and organisational results.

Although many see flexible working as a set of established and clearly defined HR practices, my research indicates that flexible working is actually an ambivalent experience far exceeding the set of approved flexible work arrangements and practices enshrined in formal HR policies.

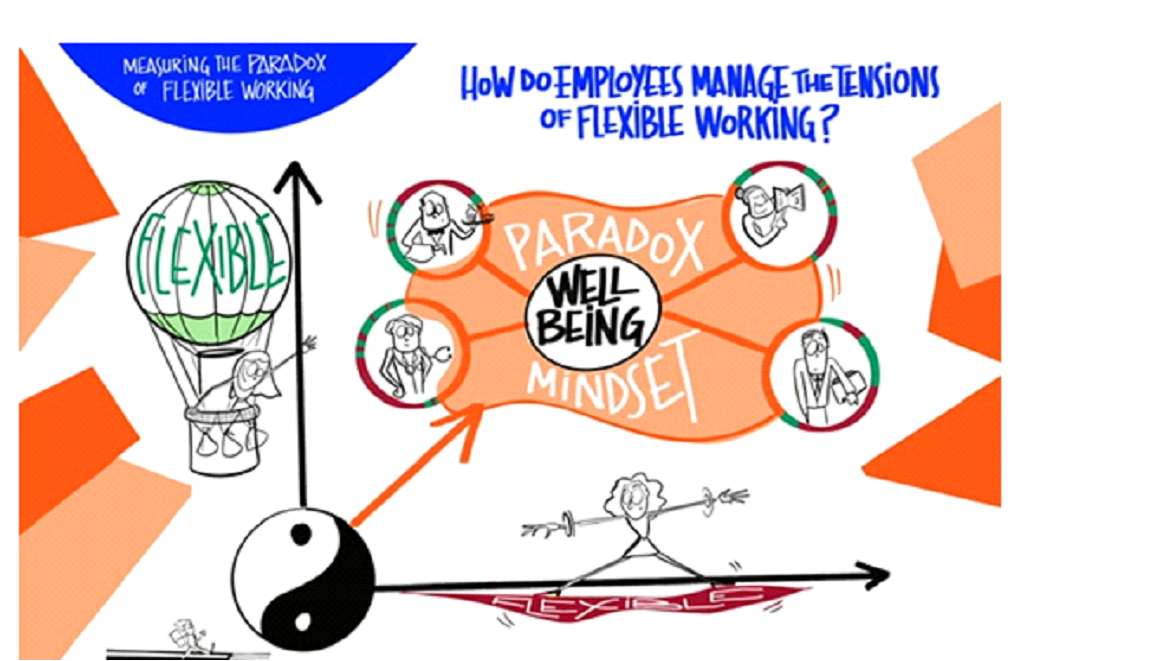

On the one hand, employees experience flexibility as an inducement that is provided to them. It is perceived as a perk that grants them agency to manage work responsibilities autonomously. As reflected in the following illustration, this side of flexibility can be depicted as an air balloon: it enables individuals to make choices related to their work (particularly where and when they work) and as a result they experience more autonomy and freedom.

Figure 1. How do employees manage the tensions of flexible working?

Source: ESCP. Illustration by Frederic Debailleul.

However, on the other hand, individuals also experience flexibility as a contribution they are expected to provide to their organization, so that the organisation can adapt to environmental changes and demands. Experiences of flexible working also include being available outside work hours, working overtime, or working wherever you are. This requires employees to stretch as illustrated in the figure, in terms of availability or the use of their abilities. Interestingly, many organisations forget this side of the story and regard flexibility solely as a benefit for employees. Unfortunately, that approach is misleading. It forgets half of the actual experience and may lead to the wrong conclusions regarding the effects flexible working has on employees.

What is interesting is that these experiences of flexibility are tangled. For example, having flexible work hours means that you can take time off on a Wednesday to take your kid to the doctor but also that you might work over the weekend. Working remotely means you might choose to work from home but also feel required to connect to a meeting while on holidays. Indeed, Eurofound and the International Labour Office (2017) underline that the growth in flexible working schemes has been driven to a large extent by organisational goals such as increased productivity and performance. Flexibility is thus a key element of survival in competitive and technologically challenging environments. At the same time, flexibility involves empowering employees and giving them control over certain aspects of their jobs. Numerous organizations have put them in place to help employees meet their work and life demands simultaneously.

Since flexible working creates ambivalent, contradictory and tangled experiences, a growing literature suggests it should be understood as a paradox (Putnam et al., 2014; Hornung and Hoge, 2019): it is a complex experience, entailing continuous tensions. Flexibility as an inducement and flexibility as a contribution push and pull against one another: they are two sides of the same coin. This view is illustrated in the figure by the Taoist symbol of Yin and Yang, which represents how apparently contrary forces may really be complementary and interlinked.

This approach to flexible working opens up numerous questions and research avenues. To what extent are organizational leaders managing flexible workers with this paradox in mind? What sort of role do line managers play in individual experiences of flexible working? Is the experience similar across different types of occupations and industries? Has the pandemic changed both experiences of flexibility as a contribution and flexibility as an inducement similarly?

Most importantly from my perspective, we know little about the impact that these contradictory experiences have on workers’ well-being. Do they influence different dimensions of well-being (e.g., physical, psychological, social) equally? Does their evolution over time affect well-being in one lifespan? Does having a paradox mindset (i.e. “the extent to which one is accepting of and energized by tensions”) (Miron-Spektor et al., 2018; p.) help workers preserve their well-being? Flexible working has been associated with positive employee outcomes (such as increased happiness and engagement, or reduced exhaustion) but has also been argued to encourage work intensification, detachment problems or burnout. Adopting a paradox approach may be a way to move forward in understanding these contradictions and unpacking employee lived experiences of flexible working.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Victoria Heath on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy