Why are workplaces often devoid of humour, if having a good laugh brings many benefits to people and organisations? Teresa Almeida and Cecily Josten look at the research on workplace humour and write that having, and showing, a sense of humour is a way to demonstrate authenticity and come across as more human. They argue that more experimental research is needed to test the benefits and downsides of humour interventions and how to best leverage humour to achieve positive work outcomes.

An average four-year-old toddler laughs 300 times a day. In comparison, it takes the average 40-year-old two and a half months to laugh that many times. Two researchers at Stanford University, Jennifer Aaker and Naomi Bagdonas, report on this “humour cliff” in their book, “Humor Seriously”. In a 2013 Gallup study, 1.4 million people across 166 countries were asked a simple question: Did you smile or laugh a lot yesterday? For those between 16 and 23 the answer is yes. After the age of 23, the answer becomes no. In fact, we do not start smiling again until the age of 70 or 80.

This age timeframe has a striking correlation with the average working age and lets one wonder to what extent work makes us humourless. Aaker and Bagdonas argue that humour is an understudied topic but can be a key skill for teams and business leaders to, amongst others, improve work outcomes and benefit individuals intrinsically. With teamwork and task complexity increasing constantly, having, and showing, a sense of humour is a way to demonstrate authenticity and come across as more human. And during a global pandemic, laughing seems an essential (and potentially the only) tool for successfully juggling everyday work and private life.

The positive impact of humour

Humour is a universal phenomenon, present in all cultures and individuals. Biological research suggest humans are genetically predisposed to laugh, meaning a sense of humour is hardwired into our brains (Marinkovic et al. 2011). Humour is also inherently a social phenomenon – we are approximately 30 times more likely to laugh in a social context than when alone (Provine and Fischer 1989). And cultural norms further determine both the context and the subject matter in which laughter is appropriate (Gervais and Wilson 2005; Martin and Ford 2018).

So, it is perhaps surprising that workplaces are often void of humour. It seems that in the pursuit of professionalism and good business reputations, we have forgotten the value and positive impact of humour. Studies show that bringing humour into organisations can actually improve work outcomes such as individual and group performance, satisfaction, and well-being. To understand humour’s impact on teams, Lehmann-Willenbrock and Allen (2014) observed the behaviour of 54 teams in industrial organisations in Germany over two years by videotaping their team meetings. They found that human patterns in meetings triggered positive socioemotional behaviours such as the active encouragement of participation and problem-solving behaviours like seeking new ideas or solutions. Further, humour patterns in meetings were positively related to team performance (e.g., reaching targets or self-reported team efficiency) both immediately and after two years.

According to a meta-analysis of humour in the workplace, not only work performance but also employee satisfaction, group cohesion and employee health are all linked with humour. Across 49 studies, the authors also found that it is an effective way to decrease burnout and stress, implying humour can not only benefit teams but also individuals (Mesmer-Magnus et al. 2012). However, these studies focused on positive humour, that is, humour that has a positive or beneficial intention.

To be or not to be… funny

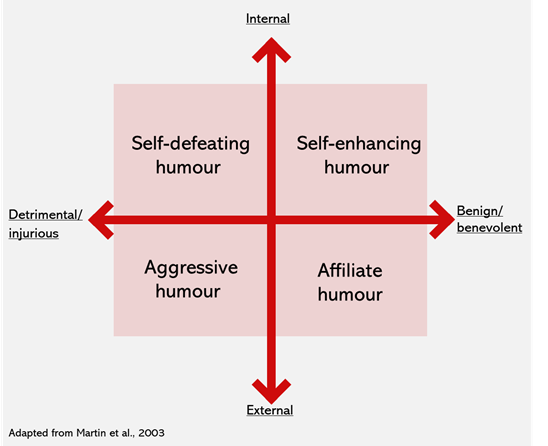

With the many positive effects humour has on people and the work environment, it is still crucial to distinguish among different types of humour and highlight the specific kinds that leverage positive work outcomes. As conceptualised by Martin and colleagues (2003) humour styles vary across two dimensions: social vs self and positive vs negative. Positive humour can therefore be either affiliate, when used to enhance relationships or self-enhancing, which is more internally focused. Both have been the main focus of academic studies and are thought to generally enhance work outcomes and increase openness and creativity (Lang and Lee 2010). Contrasting with these are detrimental humour styles (aggressive or self-defeating), which have been shown to have a more negative relationship with happiness (Ford et al. 2014).

Figure 1.

An interesting study by Bitterly and Brooks (2017) explored the riskiness of humour. In a series of experiments, they manipulated the appropriateness of jokes and their success in different settings. In one of the experiments, they had a confederate give a testimonial about a travel service to Switzerland. In the serious condition, a confederate said “The mountains are great for skiing and hiking! It’s amazing!”, while in the humour condition they added “The mountains are great for skiing and hiking, and the flag is a big plus!”. The researchers found that a successful joke – that is a joke that is both funny and appropriate – signals high confidence in and competence of the joke teller. However, an inappropriate joke signals confidence but also low competence, harming the status of the joke-teller. Importantly in this study, the confederates were always male. Indeed, there has been little research considering the impact of gender in the use of humour, but a recent study indicates that while humour can improve the status of men, it does not necessarily pay off for women – according to Evans and colleagues (2019), humorous women were ascribed less status compared to their more serious female counterparts, while the opposite was true for men.

A way to mitigate the potential risk of humour is to use humour while being aware of the relationships between the people in the room, and the social norms of the environment (Bitterly and Brooks 2020). Sarcasm can boost creativity, as it requires a higher-level abstract thinking, but it can also lead to higher perceived conflict. Self-deprecation can demonstrate warmth when disclosing a personal fault, but it could also backfire if in the presence of superiors as it can diminish the credibility of the joker (Romero and Cruthirds 2006). And in leadership settings, the relationship between leaders and their teams – more than the type of humour – is key for its success (Robert and Dunne 2016). If there is a positive relationship, humour, regardless of type, enhances job satisfaction. However, if the relationship is negative, humour won’t fix it. So, rather than focusing on being incredibly funny and risking hitting the wrong tone, the goal could be to achieve an atmosphere of levity at work or in other words having fun at work.

A culture of levity and psychological safety

Bringing humour to work does not mean figuring out how to be the best stand-up comedian in the office. Instead, using humour can simply be thought of as a way of sharing moments of lightness at work to propel relationships forward and balance the seriousness of everyday tasks. According to Scott Christopher, author of “The Levity Effect: Why It Pays to Lighten Up”, levity is about putting others at ease, being friendly, warm and authentic. It is a learnable skill that enriches workplace culture. Here, Aaker and Bagdonas add that humour does not have to be particularly good to trigger positive emotions and cooperation.

By building positive emotion, teams become more open-minded, resilient, and motivated – building psychological, social and physical resources. As humour or levity increase, so does divergent thinking, making teams more apt to solve creative and complex problems (Delizonna 2017). Psychological safety, the degree to which people perceive their work environment conducive to risk-taking (Edmondson 2002) in particular, has been shown to play a role in enabling performance, and mediating the relationship between leader inclusiveness and performance (Edmondson and Lei 2014).

Interestingly, promoting humour and psychological safety is potentially a virtuous circle – a leader showing vulnerability by making a self-deprecating joke is rated as more supportive and open to communication from its team members (Smith & Powell 1988). Openness of communication and positive mood in turn improve psychological safety (Friedman et al. 2007), which motivates individuals to seek stimulation and incentives such as making jokes and being creative. While still an emerging area of research, Amy Edmondson, an expert in psychological safety at the University of Harvard, argues that to make psychological safety work, it is important to have a team culture that embraces error and deals with failure without fear of punishment. Humour, as well as other interpersonal, skills can determine its success (Edmondson 2002) and be a stepping stone towards more psychological safety, collaboration and inclusion.

The punchline

“Two hunters are out in the woods when one of them collapses.

He doesn’t seem to be breathing and his eyes are glazed.

The other guy whips out his phone and calls the emergency services.

He gasps, “My friend is dead! What can I do?”.

The operator says “Calm down. I can help. First, let’s make sure he’s dead.”

There is a silence, then a shot is heard.

Back on the phone, the guy says “OK, now what?”

If you laughed, you are not alone. According to almost two million people from 70 countries, this is the funniest joke in the world. The results come from an experiment by psychologist Richard Wiseman and his team, which were awarded a Guinness World Record for conducting one of the largest experiments in history. Even if you didn’t, their curious study exemplifies that a sense of humour is indeed universal.

While still an under-researched area of our work lives, it seems that we could benefit from laughing more at work. An organisational culture that embraces innovation with a smile can improve openness to ideas, risk-taking and performance. And to better understand the impact humour has in the workplace, more experimental research is needed to test the benefits and downsides of humour interventions and how to best leverage humour to achieve positive work outcomes.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The post expresses the views of its authors, and do not necessarily represent those of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Danilo Batista on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

I completely agree that humour is needed in a work environment, in moderation of course. It not only helps to brighten the mood, it helps with bonding in a department and can help to relieve stress as well.

Yep, totally agree, I work in a large IT company and always make sure I introduce some sort of humour into every meeting, and you can really tell how it lifts the tension, helps people to be more empathetic and kinder to each other, and makes it a much happier experience.