Golden visa programmes are likely to become more attractive for countries searching for a shot of foreign investment to recover from the COVID-19 crisis. But do they work? Kristin Surak writes that golden visas typically bring in no more than 0.3 per cent of GDP in revenues and aren’t large enough to make a difference in real estate markets, except for Greece. Citizens from other EU countries represent a much larger proportion of foreign investors and are more likely to destabilise real estate markets than the wealthy, often racially distinct “others” from outside Europe who sign up for golden visa programmes.

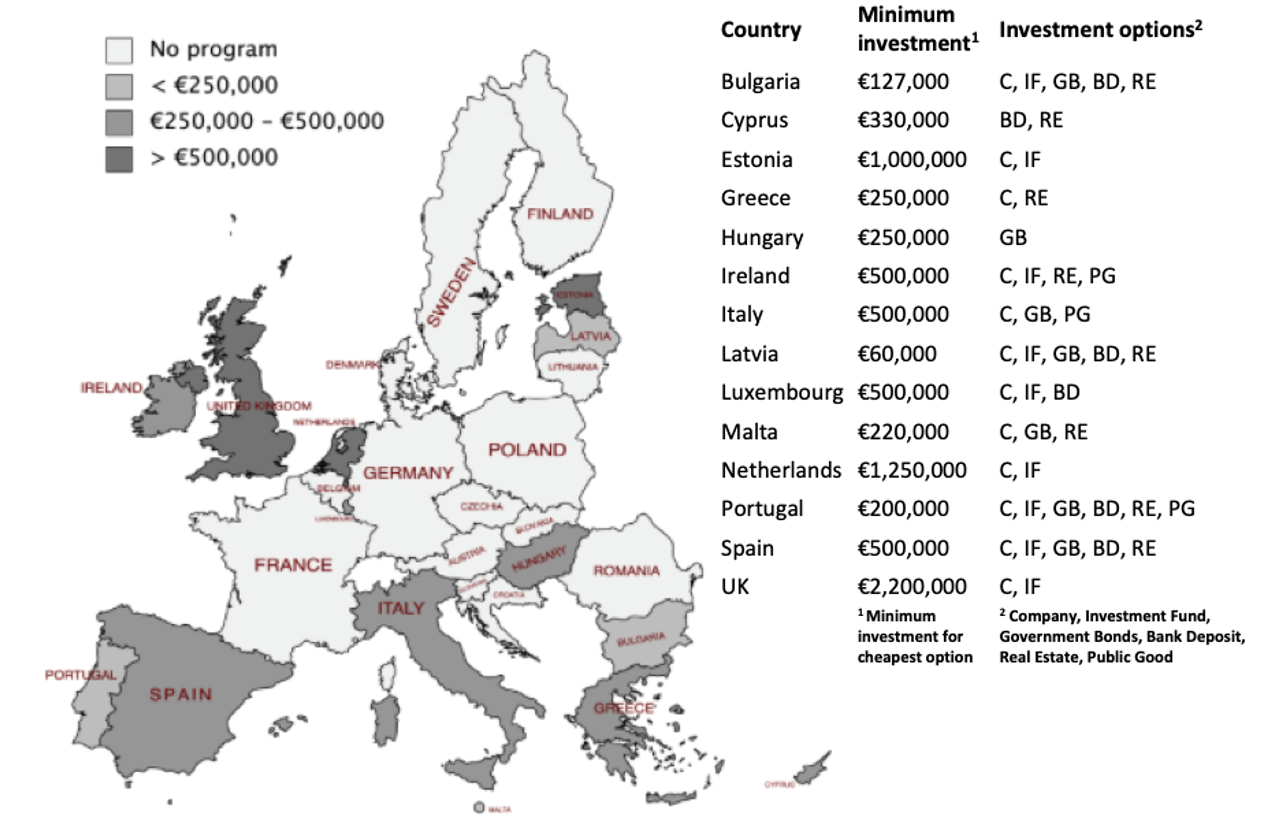

Half of all EU member states, along with the UK, hosts “golden visa,” or “residence by investment” (RBI) programmes, which offer residence permits to investors. The right to reside in a country can be extended on many grounds, but these schemes often raise eyebrows because the investment is “passive”. To qualify, the investor just parks his or her money in the country – typically around €250,000 or so in real estate, government bonds, or business investments.

These channels stand apart from business or entrepreneurial programmes, which require an “active” involvement in the investment, i.e., besides economic capital, the applicant also contributes human capital to the country. Golden visas are also different from “golden passports,” or “citizenship by investment” programmes because what’s on offer is residence, not citizenship. Those seeking golden visas tend to be the newly wealthy from outside the Global North, with Chinese accounting for around half of all demand.

Golden visa programmes are ostensibly set up to meet economic needs – but do they? They have been accused of being a mere symptom of neoliberalisation that possibly destabilises real estate markets and brings negative macroeconomic consequences. Analysing new data with Yusuke Tsuzuki, I investigated the economic origins and outcomes of the residence by investment programmes in the EU, including the UK during its period of membership. The study is part of the first systematic investigation of the uptake and outcomes of these programmes in Europe.

Figure 1. Residence by investment (RBI) programmes in EU member states to 2020

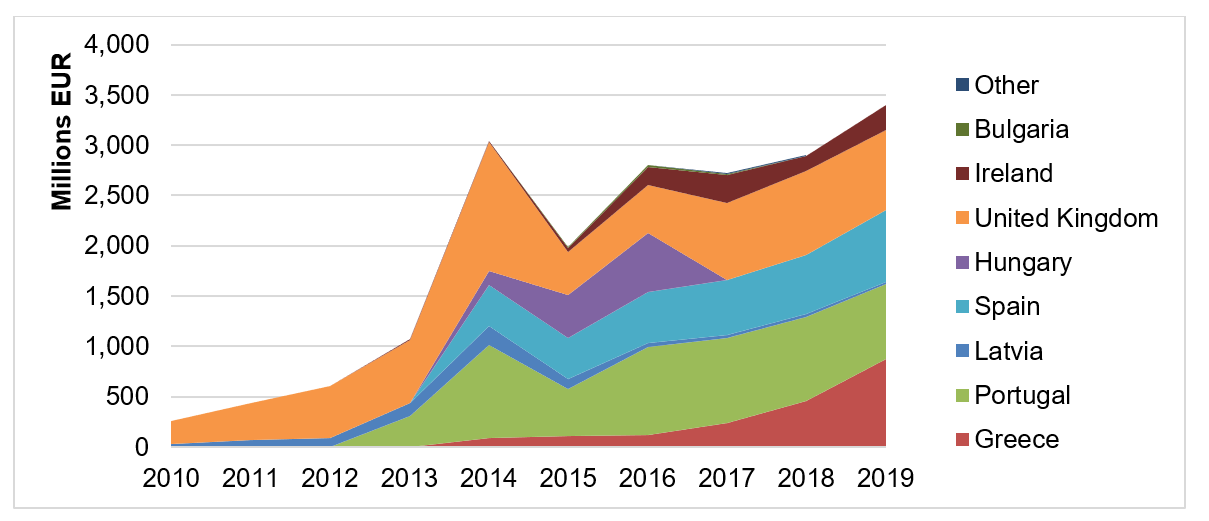

Currently, the programmes attract around €3 billion in investment to the EU annually. However, the yields are not spread equally. Most of the money goes into Greece, Portugal, and Spain, each of which takes in around €750 million through the programmes. The recently Brexited UK accrues a similar amount each year as well. It’s not merely pocket cash at stake.

Figure 2. Revenue by country

Sources: Bulgaria: Investment Bulgaria. Estonia: Police and Border Guard Board. Greece: Enterprise Greece. Hungary: immigration and Asylum Office. Ireland: Department of Justice and Equality. Latvia: office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs. Luxembourg: Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs. Netherlands: Immigration and Naturalisation Service. Portugal: Immigration and Border Service. Spain: Ministry of Labour and Migration. UK: Home Office.

What makes countries turn to golden visas as a revenue source? Carrying out a regression analysis, we found that countries do indeed start programmes following economic declines and are more likely to do so after economic crises. They also tend to select investment options tooled to meet economic needs. Notably, a decline in GDP growth is not correlated with greater restrictiveness, but rather the opposite. That is, governments of weakening economies are more likely to launch golden visa schemes, suggesting that they are treated as more like economic tools than immigration-related ones.

Furthermore, it doesn’t matter whether the political left or right is in power: governments from across the political spectrum implement the programmes. Nor do countries start programmes because others have them: there is no contagion effect. We also found that investors, when they are shopping for options, behave like tourists and profit-oriented businesspeople, rather than as settlement-oriented immigrants. Conditions related to the long-term quality of life were not significant, while tourism and the potential to make a profit on the investment were. The investors appear more like mobile “flexible citizens” who use the programmes to multiply their options and their finances, rather than as a tool for immigration.

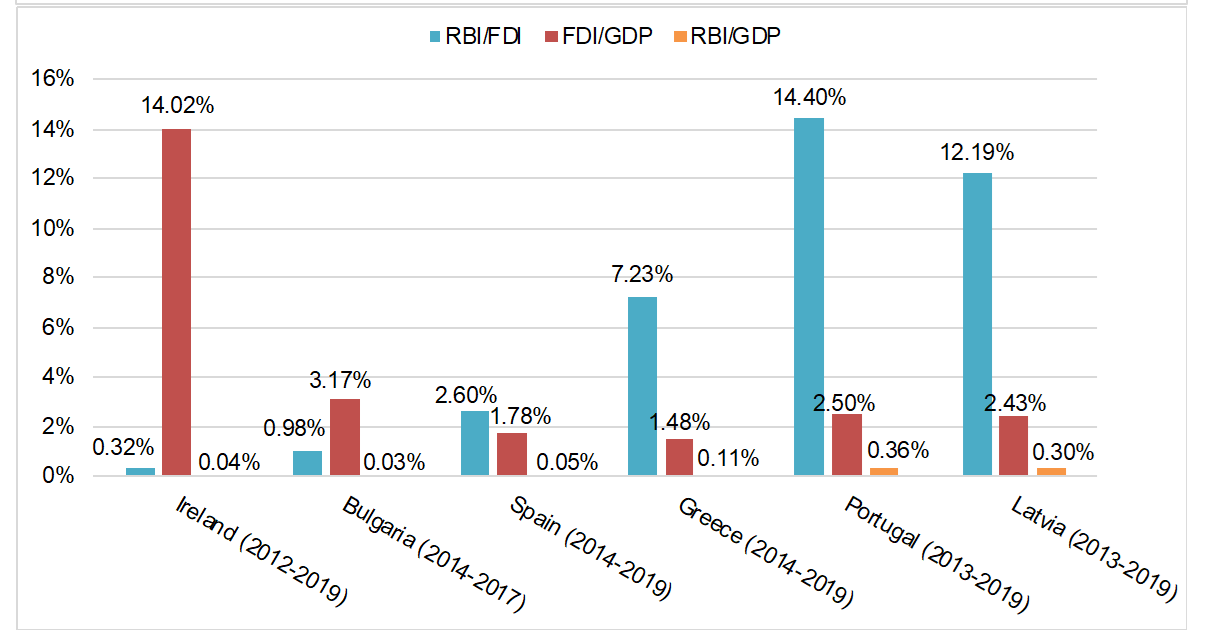

What about the economic impact? In some countries, the programmes represent a sizeable proportion of foreign direct investment (FDI). In Latvia and Portugal, the golden visa schemes have brought in well over 10 per cent of FDI over time, and in Greece it tops 7 per cent. Yet, put into perspective, the numbers are less eye-catching: in these countries, FDI is only a small proportion of the overall economy. And, indeed, in none of the countries do programme revenues bring in more than 0.3 per cent of GDP. As such, there is little risk of macroeconomic destabilisation to the national economy.

Figure 3. Residence by investment (RBI) as a proportion of foreign direct investment (FDI) and gross domestic product (GDP)

Sources: Bulgaria: Investment Bulgaria. Greece: Enterprise Greece. Ireland: Department of Justice and Equality. Latvia: Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs. Portugal: Immigration and Borders Service. Spain: Ministry of Labour and Migration. Eurostat: FDI. World Bank: GDP.

Sources: Bulgaria: Investment Bulgaria. Greece: Enterprise Greece. Ireland: Department of Justice and Equality. Latvia: Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs. Portugal: Immigration and Borders Service. Spain: Ministry of Labour and Migration. Eurostat: FDI. World Bank: GDP.

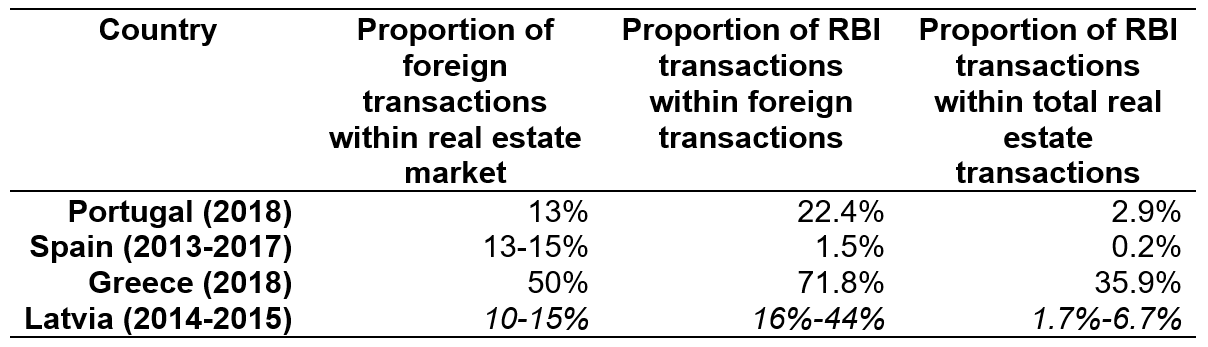

How about real estate? Many have been concerned that residence by investment programmes can price locals out of housing. Our findings do indeed show that when investors have multiple investment options before them, they almost invariably select real estate over possibilities like investment funds, bank deposits, government bonds, and charitable contributions. To truly investigate the impact on real estate value requires neighbourhood-level data, which we don’t have. However, the available country-level data suggest that real estate destabilisation through the programmes is not a great concern. In the countries with the biggest programmes, golden visa investments represented only a small proportion – under 5 per cent and typically much less – of total real estate transactions.

The programmes simply aren’t large enough to make a difference. Indeed, citizens from elsewhere in the EU represent a much larger proportion of foreign investors and are far more likely to destabilise real estate markets. However, they have not caught the attention of the media in the same way that wealthy, often racially distinct “others,” from outside Europe do. There is, though, one very important exception, namely Greece. In 2018, the country’s golden visa programme accounted for over one-third of all real estate transactions. In this case, destabilising of the property market through the programme is a real possibility.

Table 1. Significance of residence by investment (RBI) within the real estate market

Note: italicised numbers represent estimates. Sources: Portugal: Idealista and Registradores. Spain: Ministry of Labour and Migration. Greece: Enterprise Greece. Latvia: Viesturs, Pukite, and Nikuraze (2017).

What does the future look like for these programmes?

The economic turmoil brought on by COVID-19 is likely to increase the attractiveness of these options for countries searching for a shot of foreign investment that can go straight into the arm of economies in a COVID coma. It’s also likely to increase the attractiveness of such programmes to wealthy people looking to hedge their risks by securing mobility options.

Before the pandemic, national-level health statistics were insignificant in the selection programmes – and one might also note that all EU countries require applicants to demonstrate that they have private health insurance. But the significance of health care as a decision factor may change going forward. COVID-19 may also bring a shift away from a short-term “tourist-like” calculation and toward a more medium-term calculation, as people look for a place to stay for longer stints. Given the market dynamics, it may be that even as Brussels pressures countries to end such schemes, they instead simply adapt them – perhaps by adding greater demand for human capital contributions, effectively transforming them into more active business investor programmes – rather than cut this easy revenue source entirely.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on “Are Golden Visas a Golden Opportunity? Assessing the Economic Outcomes of Residence by Investment Programs in the EU”, by Kristin Surak and Yusuke Tsuzuki, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (2021).

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of LSE Business Review or The London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Featured image by Hello Lightbulb on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy