Finance professionals have higher risk preferences and monetary motivation than the population as a whole. Max Deter and André van Hoorn analyse data on 465 bankers in Germany surveyed over 2,000 times between 2000 and 2017. They show that the preferences for risk and money are already present before they start to work in finance. The results indicate a business norm in the financial sector that attracts professionals who think in a riskier and more income-focused manner.

The financial sector plays a crucial role for the economy by managing risk, providing price signals and promoting economic opportunities. Why then is the sector perceived as highly selfish and even dishonest among professions (Ashraf and Bandiera, 2017)? Compared to medical doctors, for example, many financial activities, such as wealth management, are associated with much higher (perceived) private than social returns (Zingales, 2015).

Since the financial crisis in 2007/08, the financial sector came publicly under fire with lawsuits involving the causes of the crisis, the Libor manipulation, tax evasion and money laundering. Political blame has often been attached to a ‘failure of professionalism and ethics’ (British Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards, Economist, 2014). But do financial professionals think and behave in a way that might have contributed to the scandals?

Many studies have sought to assess the values and culture among professionals in finance. Experiments with bankers show that they behave more dishonestly (Cohn, 2014), but other researchers are reluctant to reach the conclusion that the business culture of bankers is particularly problematic (Vranka, 2015; Hupé, 2018).

Holmen et al (2021) find in an experiment that bankers have a riskier and less pro-social behaviour because of different group characteristics, such as a higher share of male and more educated professionals. Van Hoorn (2015) shows in cross-sectional survey studies that the pro-social values of financial professionals are only negligibly lower when holding personal characteristics constant.

This study adds to the literature on banking culture by observing professional bankers over time. With large-scale data from Germany (GSOEP) on 465 banking professionals that are surveyed 2,391 times between 2000 and 2018, the researchers can analyse their self-stated preferences of risk and monetary motivation before, during and after financial employment.

Moreover, we can compare preferences to almost 300,000 observations of the general population during that period. This way, it is possible to differentiate between a selection effect – that is, whether individuals with certain preferences are more likely to start working in finance – and a socialisation effect – that is, whether preferences stem from an indoctrination during work in finance.

Holding personal characteristics such as age, education, qualification and the duration in the current employment status constant, we find that individuals with higher risk and monetary preference have a significantly higher probability to start working in finance.

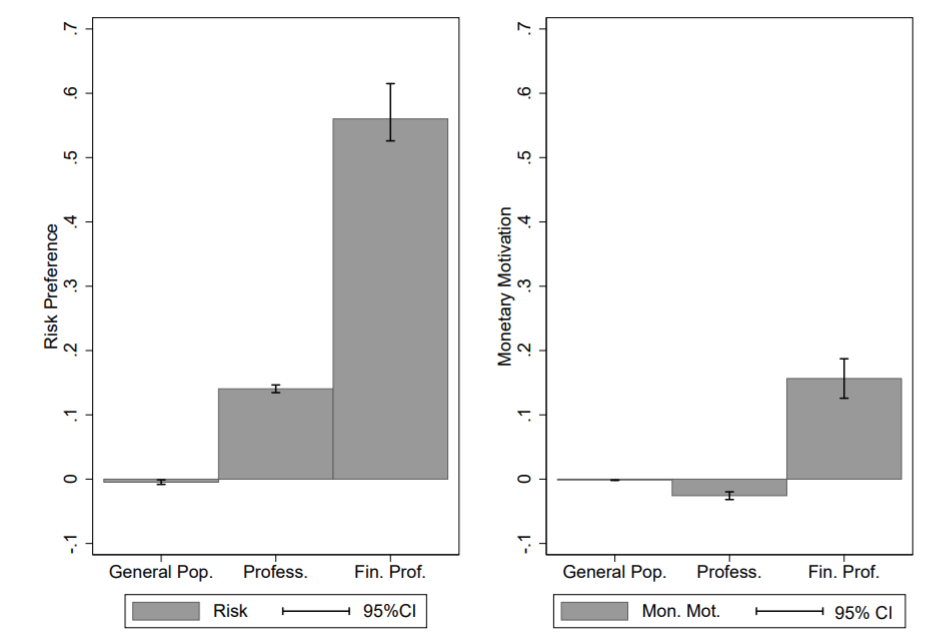

Figure 1. Averages of preferences by group

Note: The graph shows the averages and confidence intervals (95 percent) of both economic preferences for the whole population, professionals, and financial professionals. Data cones from the GSOEP

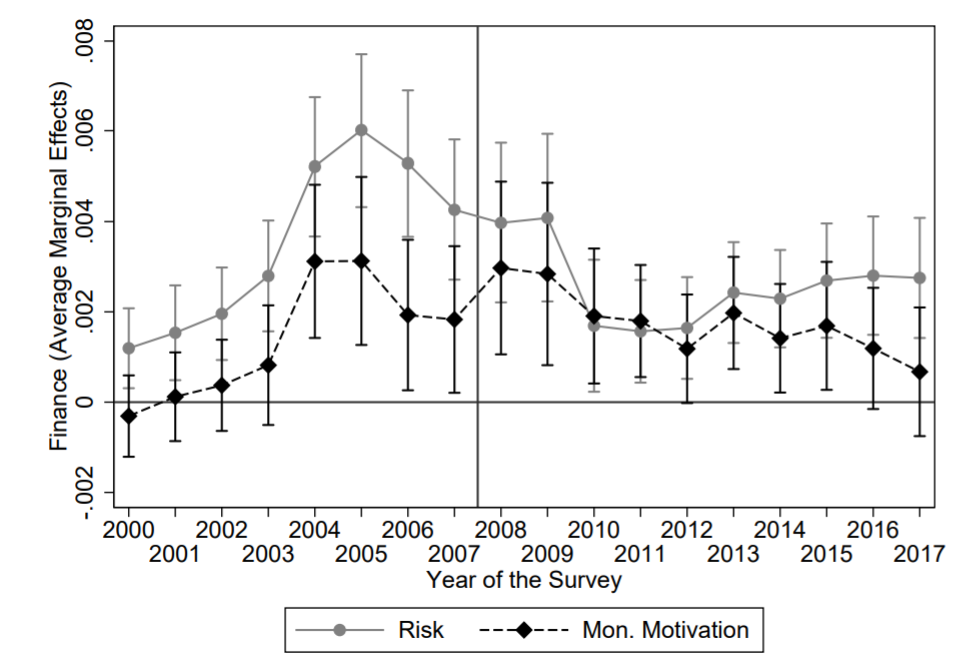

Figure 2. Economic preferences and financial employment, by year

Note: Graph shows the average marginal effect (AME) of Economic Preferences and financial employment by year. AME were calculated from a logit regression of a variable on financial employment on the individual preference, interacted with year dummies. Data is taken from GSOEP (see Section 2). 95 percent confidence intervals are shown. The vertical line represents the financial crisis in 2007, the horizontal line the zero effect. Own depiction

More precisely, individuals entering finance show 40% of a standard deviation higher risk preference, and a 12% higher monetary motivation than the general population.

Concerning the question of whether economic preferences are shaped because of a pre-existing business culture, bankers who already work in finance have a similar risk premium, but a 20% higher monetary motivation, an indication for a socialisation of monetary importance during the time in the sector. Looking at economic preferences over time there is a peak in the average risk preferences in the years preceding the financial crisis in 2007/08.

The results are important since they indicate a business norm in the financial sector that attracts professionals who think in a riskier and more income-focused manner. Risky behaviour can lead to welfare losses (Barber, 2001) and a low pro-sociality can cause weaker contract enforcement (LaPorta, 1996).

We conclude that changing the culture in the finance industry requires a concerted effort involving not only recruitment and retention but also upending extant socialisation processes.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Motivated by Money: Evidence on the Personalities of People who Choose to Work in Finance, presented at the Royal Economic Society’s Annual Conference 2021.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Hunters Race on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy