Management pays a lot of attention to new ideas and cutting-edge technologies, but most of their resources are consumed by mature legacy technologies that are often not actively and rigorously managed. The reasons are often cultural and political. Hervé Baratte and Jonas Vetter have devised a visual matrix to help teams understand which technologies bring the most potential to businesses in the long run.

Most corporate innovation strategies have one thing in common: they focus heavily on breakthrough innovations and novel technologies. There are, of course, good reasons why breakthrough innovations draw senior executives’ attention: if successful, those “big bets” have the potential to transform the way value gets created and distributed in an industry, eventually changing the competitive landscape.

Yet, this poses a dilemma for many incumbent chief technology officers (CTOs). On one side, the lion’s share of management attention and enthusiasm is taken by new ideas and cutting-edge technologies. On the other side, most resources are consumed by legacy technologies that have accumulated over years and decades. Often, those mature technologies are not actively and rigorously managed. They simply stay the course, absorbing incremental resources that could be shifted into more assets in the technology portfolio.

We have regularly seen this at play among well-known firms across different sectors, from fast moving consumer goods to chemicals to automotive. These companies tend to overinvest in their legacy technologies. Such investments are often considered a given. The legitimate question of whether investments in incremental technological improvements hold any significant customer value is too often left unasked.

But challenging the status quo is easier said than done. Leaders often hesitate to lay hands on the “holy cows” in the technology portfolio. Why? The reasons companies continue investing additional funds in mature technologies longer than they should are often cultural and political, which tend to transcend rational considerations like strategic differentiation and capital allocation. Mature technologies typically have strong owners and advocates within organisations. Rooted in the status quo, these groups are predisposed to resist change, defending their territory. Furthermore, as these legacy technologies have been around for a long time, their advocates are often some of the most established characters in the company.

How then should CTOs challenge the status quo? In our experience, a critical first step is to create awareness within teams through a “visual awakening.”

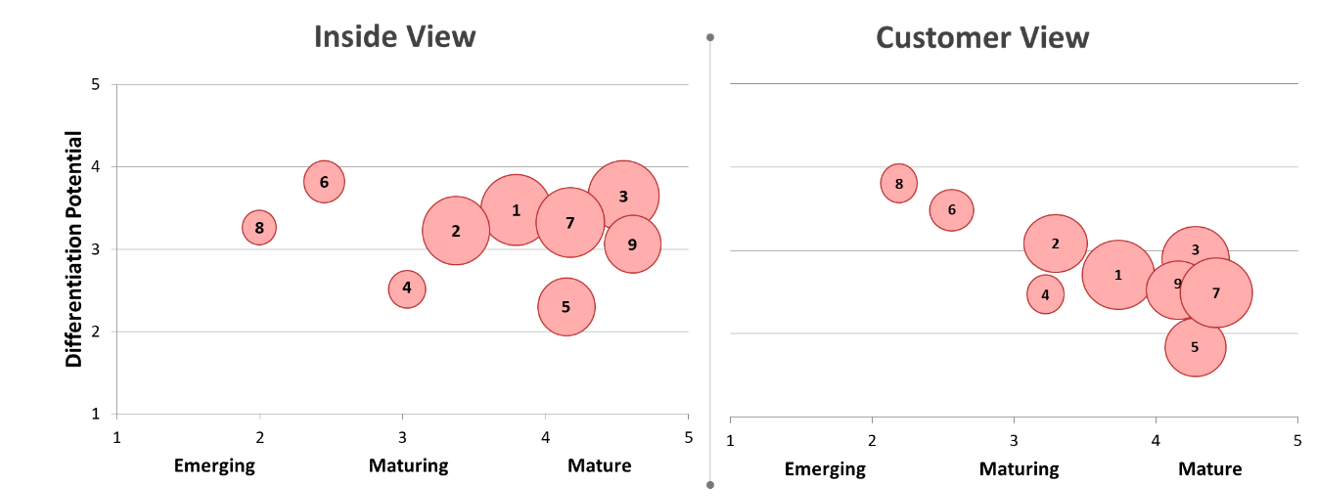

We suggest applying a simple but powerful visualisation matrix: on the horizontal axis the team – a cross-functional group of business and R&D managers from different units – maps the maturity of their technologies over three phases (emerging, maturing, and mature) with the size of each bubble indicating the annual investment. On the vertical axis, we ask the team to evaluate the differentiation potential, i.e., the strategic edge implicit in the technology, on a scale from one to five.

For many team members this will be the first time they see a comparative picture of the entire portfolio rather than the view of one isolated technology at a time. This helps to correct biases and misperceptions and sets the technologies into a broader strategic context.

After the technologies have been mapped internally, we repeat the exercise with a group of customers, guiding them with a standardised set of questions. Comparing the customers’ evaluation of value against the internal team’s is an eye-opening experience. In many cases, the team overestimates the differentiation potential of their technologies in respect to their customers’ perception.

In the case of a specialty chemical company serving the life sciences sector, the team mapped the nine most resource-intensive technologies along the maturity continuum and then evaluated their differentiation potential. After the exercise, we repeated the mapping with a set of key customers. The result was striking. As shown in the picture below, the chemical company overestimated the differentiation potential of technologies by an average of around 1.5 points, or 30%. For the costliest technologies, the difference was even wider.

Figure 1. The value of nine technologies according to the internal team and the customers

Note: Bubbles represent the nine key technologies with size reflecting the annual investment amount

Seeing this reality clearly visualised on the matrix triggered a set of tough and emotional discussions, but eventually opened the door to a fundamental reassessment of whether to continue investing in the less differentiating technologies. This was a welcome relief in the face of resource-scarcity and offered routes to financing urgently needed lab positions and equipment.

Reaching consensus on the differentiation potential of their technologies is the first and most crucial step companies need to take when rethinking the balance of their portfolios. Only then should they start discussing how to evolve operations, engage with suppliers and partners for targeted technologies, and ultimately calculate potential benefits for their bottom lines. In the previous example, the team proceeded to a second step of discussions. After aligning on the strategic value of each technology, they identified two clusters: one cluster of the less differentiating technologies where they would look to unlock resources (for example, by outsourcing to, or partnering with, suppliers), and a second cluster of the differentiating technologies to which they would allocate freed-up resources. At the same time, they introduced a process to measure the differentiation potential of each old and new technology periodically, allowing them to keep their portfolio matrix and strategic clusters up to date.

What makes technology-driven companies successful is not just their ability to turn out novel innovations. It is also about their ability to manage the old ones efficiently and effectively. To avoid the risk of misallocating resources, CTOs and their teams can apply this simple but powerful matrix to build a new perspective – a “visual awakening.” This is the foundation for the strategic discussions needed to overcome the political and cultural tethers to legacy technologies, ultimately leading to better balance in the technology portfolio.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by ThisisEngineering RAEng on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

A great post about technological shift. Thank you.