Protectionism and isolationism have been growing throughout the world, in what became known as the backlash against globalisation. Using newly assembled data for 23 industrialised, advanced democracies and global trade data, Italo Colantone, Gianmarco Ottaviano, and Piero Stanig analyse voting behaviour and track trade policy interventions. They write that international trade is not the only factor causing the upheaval. Society must manage the distributional consequences of structural change in a more inclusive way.

A lively discussion has flourished around the recent surge of populist parties across advanced democracies. One of the most salient phenomena related to the populist wave is the so-called “globalisation backlash.” In our recent CEP discussion paper, we characterise this phenomenon as the political shift of voters and parties in a protectionist and isolationist direction, with substantive implications on governments’ leaning and enacted policies. Globalisation emerges as a relevant driver of the backlash, by means of the distributional consequences entailed by rising trade exposure. Yet, the backlash is only partly determined by international trade. Other factors, such as technological change, immigration, crisis-driven fiscal austerity, as well as cultural concerns are found to play a similar role in driving the observed political shift. Borrowing from the medical literature, we describe this multi-causal nature of the phenomenon through the concept of “comorbidity”, by which different factors compound to generate the backlash.

Documenting the backlash

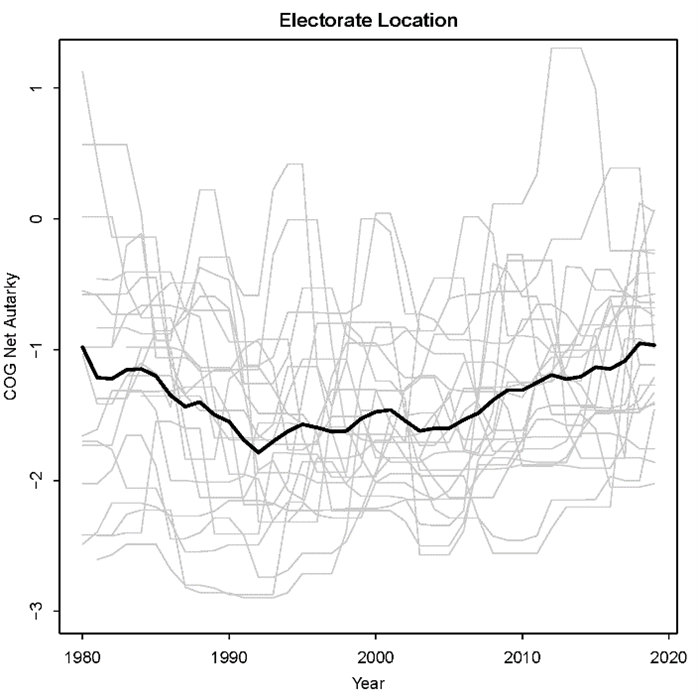

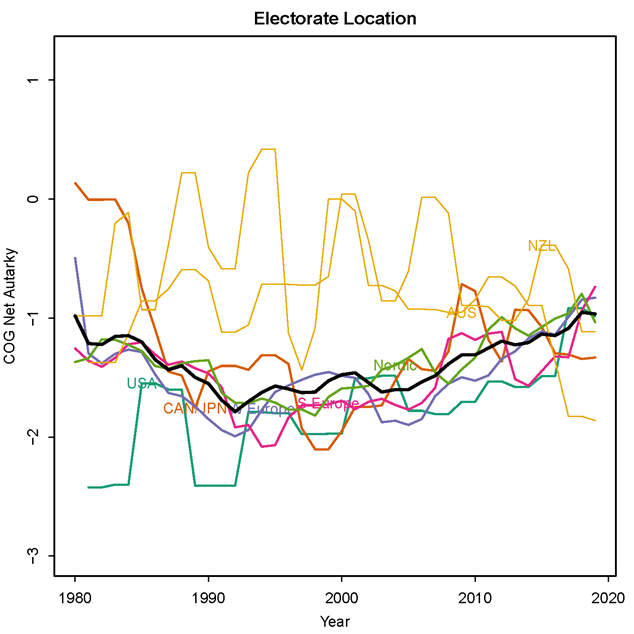

To document the globalisation backlash, we employ newly assembled data for 23 industrialised, advanced democracies, spanning Europe, North America, and Asia. The analysis covers the period 1980-2019. We start by providing descriptive evidence of the backlash in terms of voting behaviour. Specifically, Figure 1 displays the electorate location in terms of protectionism and isolationism. For each country, in each national election, this is obtained by combining two ingredients: (1) the vote share of each party; and (2) an ideology score, called Net Autarky, which reflects the stance of each party with respect to trade policy and multilateralism, based on party manifesto data. The electorate location is then computed as a weighted summation of party scores, using vote shares as weights. It is essentially the ideological centre of gravity (COG) of the electorate. The top panel reports all countries (grey lines) along with the cross-country average (dark line). The bottom panel highlights specific countries, such as the US, or groups of countries, such as southern, western, and northern Europe. Looking at the grand mean, there is a visible decline from the beginning of the 1980s until the early 1990s. This globalist wave is then followed by a protectionist shift from the mid-1990s onwards. Such a pattern is clearly detectable across most countries. The only exceptions seem to be Australia and New Zealand, which start from relatively high levels of net autarky, and display a decline in recent years. Very similar evidence is obtained when looking at the ideological location of legislatures and executives. This suggests that the shift in voting behaviour has been consequential for the composition of decision-making bodies.

Figure 1. Electorate location

Note: Figure taken from Colantone, Ottaviano and Stanig (2022). Both panels report figures referring to the electorate centre of gravity in terms of net autarky scores. In the top panel, the light grey lines refer to each single sample country; the black line is the cross-country average. In the bottom panel, we display separately specific countries and groups of countries in different colours; the black line is the cross-country average.

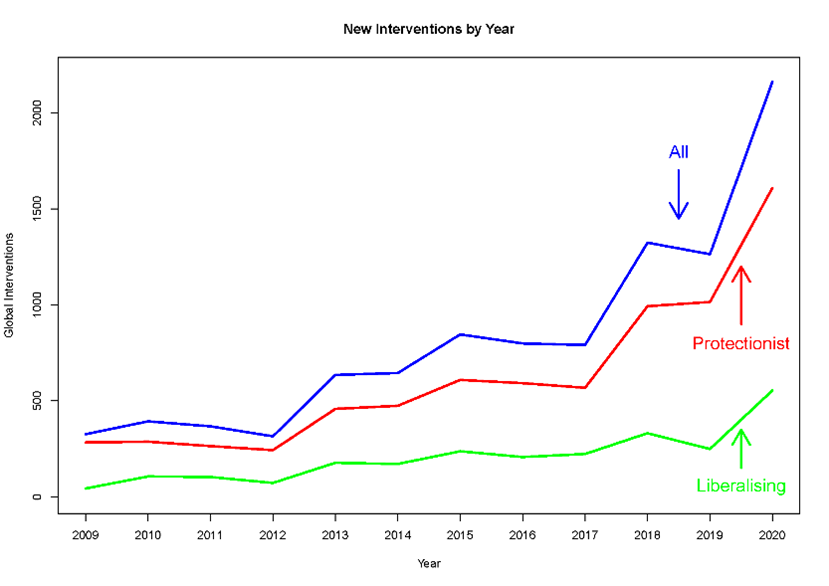

A protectionist shift is also detectable in terms of trade policy developments. In this respect, there are many recent cases in point, ranging from Brexit to the US-China trade war and the stall of the WTO Appellate Body. More systematic evidence is shown in Figure 2, based on Global Trade Alert data, according to which protectionist trade policy interventions have been growing faster than liberalising ones from the financial crisis onwards. Yet, besides such dynamics, more trade-friendly developments can also be observed. For instance, the number of active regional trade agreements (RTAs), and especially free trade areas (FTAs), has kept growing even after the financial crisis. In parallel, average tariffs have kept declining over time. However, temporary protection measures such as anti-dumping and countervailing duties have been increasingly activated, and with rising ad-valorem rates, entailing stronger protectionist effects. Overall, the evolution of trade policy seems consistent with the political dynamics described above. The picture gets instead more nuanced as we look at individual attitudes. We do not find systematic evidence of a generalised worsening in public opinion with respect to globalisation. However, large minorities, and in some cases strong majorities, of survey respondents believe they are not actually benefiting from international trade (e.g., 39% in the US and 60% in Italy).

Figure 2. Rise in protectionist measures since the financial crisis

Note: Figure taken from Colantone, Ottaviano and Stanig (2022), based on Global Trade Alert data. The green line displays liberalising interventions, the red line protectionist interventions, the blue line is the sum of all interventions.

Drivers of the backlash

What are the drivers of the globalisation backlash? A large literature has developed in recent years around this broad research question, investigating both economic factors and cultural determinants. Several studies have emphasised the role of trade, focusing particularly on exposure to surging imports from China between the early 1990s and the financial crisis. Regions more exposed to the China shock, owing to their historical industrial specialisation, have been shown to be negatively affected in many ways, ranging from higher unemployment, lower labour force participation, increased use of disability and other transfer benefits, reduced wages, as well as lower provision of public goods and worsening health conditions. This phenomenon has had political repercussions as well, leading to rising support for protectionist, isolationist, and nationalist parties and candidates. The available evidence allows us to conclude that the globalisation backlash is thus endogenous to globalisation itself. However, other factors have been found to tilt electorates in similar ways. In particular, technological progress, by means of automation of production through robots, has been shown to generate distributional consequences that are akin to those of trade, leading to similar political responses. The same holds true for crisis-driven fiscal austerity as well as immigration, which acts both as a catalyst of structural economic grievances, and as a direct determinant of political backlash.

Conclusion

Overall, it seems that globalisation is at stake also due to reasons that are not strictly related to trade. The political sustainability of globalisation—and arguably of the international liberal order—will depend on how successful society will be at managing in a more inclusive way the distributional consequences of structural change.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on The backlash of globalization, CEP Discussion Paper Number CEPDP1800.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by David Shankbone, Public domain

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.