High automation risk discourages older workers from remaining in employment. In technologically advanced countries such as Finland, generous unemployment benefits to people 59 and over ends up creating a retirement pathway. Simply pushing that age limit back increases the probability that older workers facing higher risk of automation will remain in employment. Naomitsu Yashiro, Tomi Kyyrä, Hyunjeong Hwang, and Juha Tuomala write that as governments move to discourage early retirement, employers will need to work together with employees to support longer working lives.

Countries around the globe came out of the COVID-19 pandemic with larger government debts. This occurred against a background of already challenged long-run fiscal sustainability in many countries owing to rapid population ageing, which will increase government spending on pensions and health care. Lengthening working lives, for instance by linking the retirement age to life expectancy, is a policy priority across many OECD countries. However, there are various barriers for older workers to remain employed, including declining productivity and employers’ reluctance to hire or retain older workers.

In several OECD countries, labour market institutions also create strong incentives for early retirement, notably exceptional entitlements or looser criteria for unemployment and disability benefits applied to older individuals. Closing these so-called early retirement pathways is more important than ever, as rapid diffusion of digital technologies is pushing older workers toward entering these pathways. Older workers have weaker incentives to acquire new skills that would allow them to thrive under digitalisation and automation of workplaces than younger workers, because of their shorter remaining working lives. Employers may also not find it worthwhile to upskill older workers and may instead prefer to encourage early retirement. Thus, older workers who are more exposed to new technologies are particularly likely to exit employment when they become eligible for early retirement pathways.

Technology and early retirement: evidence from Finland

Finland is one of the most advanced European economies in terms of adopting digital technologies in economic and social activities, according to the European Commission. At the same time, it offers generous unemployment benefit entitlements to older individuals, an early retirement pathway often dubbed as the unemployment tunnel. The tunnel starts at the age of 59, when individuals become entitled to a 100-working-days longer entitlement to unemployment benefits than younger age groups. If individuals are still unemployed after turning 61, they can have their unemployment benefits extended until they start drawing old-age pension, usually at 63. Several studies have identified a strong impact of the unemployment tunnel in increasing the inflow of older workers into early retirement through unemployment.

In our recent study, we found that workers in occupations exposed to higher automation risks, associated with higher shares of routine tasks or lower use of ICT skills, are more likely to enter the unemployment tunnel. The combined impacts of technological change and the unemployment tunnel are substantial. For instance, an individual aged 50 or above in occupations exposed to risks of automation that are one standard deviation higher than the average (across occupations) faces a 1.1 percentage point higher probability of exiting employment every year, when he or she is not eligible to the unemployment tunnel. This probability increases to 2.2 percentage points when the individual is eligible for the tunnel. In addition, eligibility for the unemployment tunnel by itself increases the exit probability by 1.8 percentage points, even when the individual is exposed to an average level of automation risks. The combined impact of automation risks and the unemployment tunnel therefore amounts to 4 percentage points, which corresponds to an 80% boost in the probability of exiting employment for individuals aged 57-58.

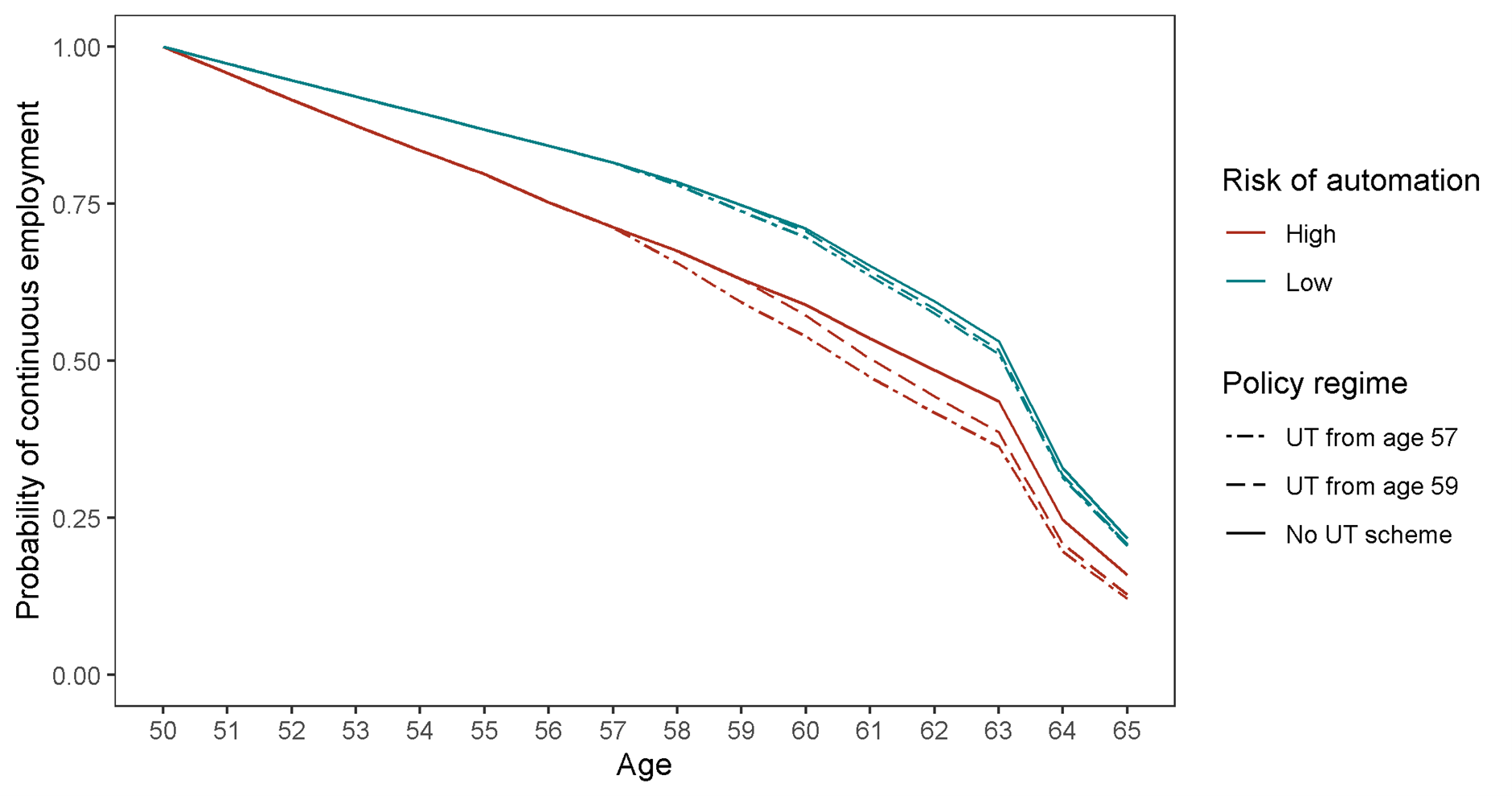

Finland in the past raised the eligibility age for the unemployment tunnel several times, each time pushing back the flow into unemployment of a high share of older workers. But whose working lives did these reforms actually lengthen? To illustrate this, we simulate the probability that a worker remains employed after the age of 50, based on the above empirical findings. An older worker’s probability of remaining in employment declines faster when her occupation is exposed to higher-than-average automation risk (see the figure below). Strikingly, reform that pushes back eligibility ages for the unemployment tunnel or abolishes it significantly improves the probability of older workers exposed to higher risk of automation remaining in employment but has little effect on employment probabilities of those exposed to lower automation risks.

Figure 1. Probability of old-age employment under different unemployment tunnel (UT) scenarios

Source: Yashiro, N., Kyyrä, T., Hwang, H., and J. Tuomala (2021), “Technology, labour market institutions and early retirement: evidence from Finland”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1659, OECD Publishing, Paris

Implications for the government and employers

As advanced digital technologies transform workplaces, workers need to update their skills throughout their working lives to remain competitive against machines and computers. This calls for an increased provision of lifelong learning and training opportunities. However, such policy must go hand in hand with labour market reforms that remove disincentives for older workers to continue working, namely pathways to early retirement. Otherwise, older workers will only have weak incentives to take up such opportunities.

The recent policy decision by the Finnish government to abolish the extension of unemployment benefits until retirement age in 2025 is likely to encourage older workers more exposed to technological change, in particular, to work longer. Policy measures are needed to increase the employability of these workers and ensure that they are not pushed out of employment by age discrimination and work arrangements that discourage older workers. Early retirement through unemployment or disability benefits has been driven by both employees’ and employers’ interests. As governments move to phase out these early retirement pathways to promote longer working lives, employers will need to work together with employees to come up with workplace arrangements that support longer working lives.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on “Technology, Labour Market Institution and Early Retirement”, presented in in the 74th Economic Policy Panel Meeting.

- The post expresses the personal views of its authors, not the official position of the OECD, VATT Institute for Economic Research, LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Nicole De Khors, under a Burst licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.