When an innovation pitch includes a range of best- to worst-case scenarios, does it affect its likelihood of being selected? The answer may vary depending on whether the project focuses on core innovation, which targets existing products and markets, or transformational ones, targeting new products and markets. Wim A. Van der Stede writes that scenario presentation can have different effects on the perceived risk of the project and the perceived expertise of the project team.

Do pitches that include scenarios—that is, a range of outcomes from the best to the worst case—affect the likelihood that an innovation project will get selected? This is an important question given how crucial innovation project selection decisions are to a firm’s competitiveness. There is a fine line between a firm being (too) prudent, selecting (too many) core innovation projects that target existing markets with products like their current offerings (and not enough transformational projects that target new markets with new products), and … a firm being (too) rash, taking (too much) risk and neglecting core innovation, threatening the firm’s leadership position in the market. Though hugely over-simplified as a juxtaposition, Kodak and Apple are commonly cited to illustrate this tension. That said, most firms probably inherently lean towards core innovations and would, under the right conditions, like to select more transformational innovations in their innovation pipeline. Does the way in which innovation projects are pitched influence this?

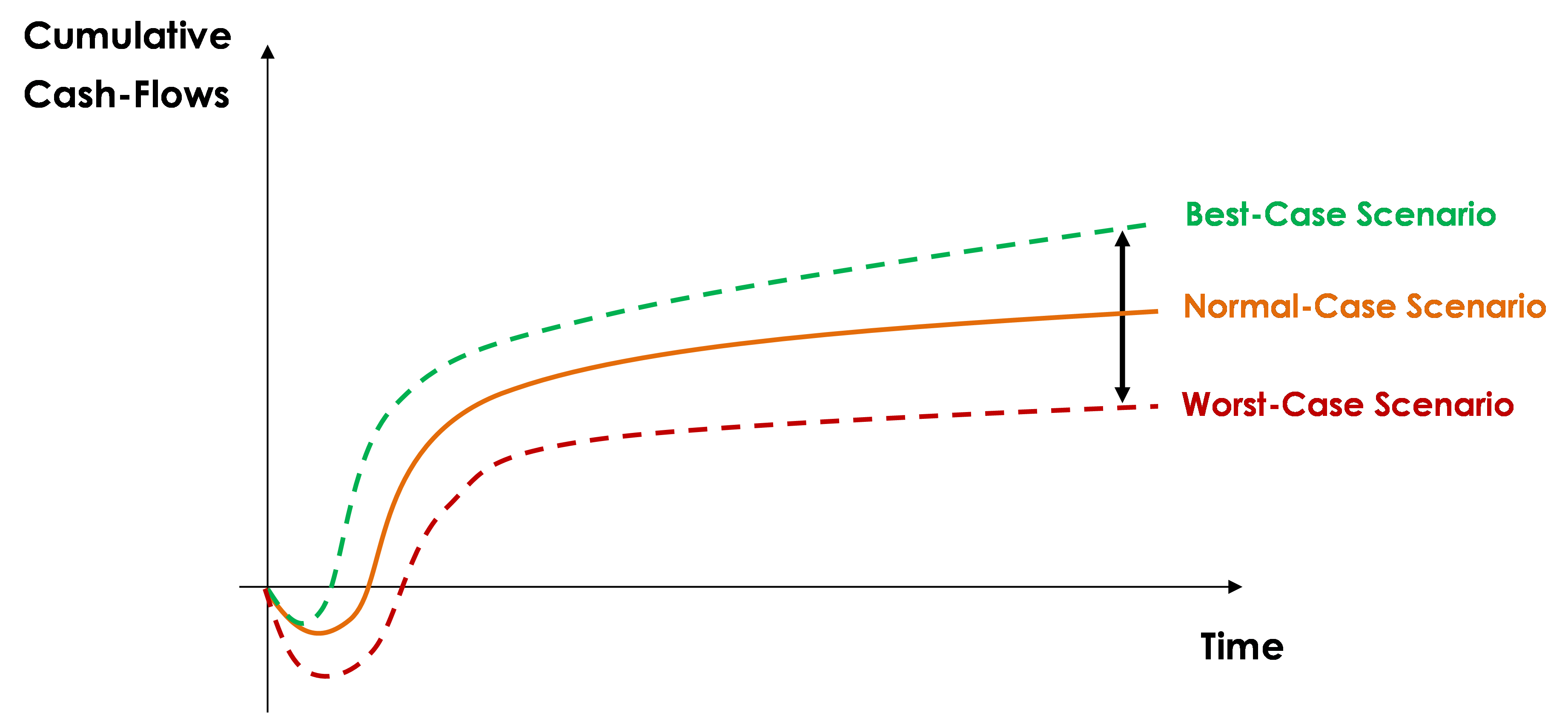

Our research suggest that it does. In their pitches to innovation decision-makers, project teams invariably present financial projections on their innovation projects, which may, or may not, include best- and worst-case scenarios (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. An illustrative innovation project’s cumulative cash flows over time: scenario presentation with best, worst, and normal case projected outcomes

Our study relies on rigorous attribution theory to develop and predict the detailed and precise mechanisms through which scenario presentation affects the ultimate innovation project selection decision; that is, whether it will be a ‘go’ or a ‘no-go’. But here is the intuition, or rather – ‘tension’. Presenting scenarios should allow those who make the selection decision to better grasp the risks involved in the project, and thus, be more confident about the project’s eventual likelihood of success. But the scenarios might also signal to these project selection decision-makers a degree of prevarication by the project team: a lack of competence to converge on a precise outcome of the project. This may lead decision-makers to perceive the project team as being less expert, undermining their confidence in the people they will have to rely on to make the project a success if they greenlight it. Hence, scenarios lay bare a tussle between some possible upside in terms of assessing the project’s risk but also some potential downside by way of possibly eroding confidence in the project team’s expertise. But maybe it depends—on what?

Even though there are other tensions and tradeoffs, the effect of scenario presentation on the perceived risk of the project and the perceived expertise of the project team is a crucial one. However, the research further explores the extent to which this tension bears on:

- whether the effect of scenario presentation on project selection is contingent on the type of innovation (coreor transformational); and

- whether is it contingent on the range of the scenarios (small or large).

One can thus immediately see a host of factors to consider. But let me give two of the most pertinent arguments from among all the possible combinations just to illustrate.

One can easily intuit how confidence in expertise of the project team would be less undermined when scenarios are presented for transformational rather than for core innovation projects because transformational projects entail more uncertainty and there is less experience to readily draw on when developing these projects that are new to the firm.

Thus, innovation decision-makers know that while project teams proposing core innovations should have access to sufficient information to develop their project’s outcome with confidence, project teams proposing transformational innovations inevitably will have to rely on much more scarce and ambiguous information and may have more credible grounds, and not just excuses, for disagreements among project team members about their project’s future.

Consequently, presenting scenarios that depict alternative plausible futures should not be surprising, and thus, is less likely to trigger negative team expertise attributions for transformational than for core innovation projects. Actually, one could even argue that not presenting scenarios for transformational projects might be a sign of incompetence, as indeed when for such projects only the normal case was presented, decision-makers would still be well aware that there must be a likely worse case, and thus, its omission from the pitch would backfire by reflecting negatively on the perceived expertise of, and trust in, the project team.

Regarding the width of the range of the scenarios, it seems plausible to accept that a wide range for a core innovation project would appear to run counter to the expected manageable risk level inherent in such projects and counter to the expectation of the project team having done its homework or being competent enough to narrow down the range. For transformational innovation projects, the opposite would be naturally expected, where such project’s inherent novelty and risk hampers the project team’s ability to narrow down the range more accurately. Given that this is expected, it is also likely to be accepted; that is, it should not reflect poorly on the team’s expertise, quite to the contrary.

So, then, should project teams present scenarios in their pitches? If so, of which appropriate range? And does the answer vary by the type of innovation?

Our findings suggest that firms should help project teams present small-range rather than large-range scenarios. I hasten to add that this appears to also hold comparatively for transformational projects. The reason is that, as wide(r) scenarios are presented, not only may the project team be perceived as not having done its homework, but it may also trigger the well-known negativity bias. That is, decision-makers are susceptible to place more weight on negative information than on positive information, thereby increasing their perception of project risk. For transformational projects, the worst case may even show a loss, which decision-makers may react to overly aversely despite the potentially large upside of the project as well. Or, as one executive we interviewed put it: “If you put in front of people a positive and negative case, they will only see the negative. They will not see the positive.” If that is the case, then presenting especially wide-range scenarios is akin to the project team shooting itself in the foot.

Hence, across the board, and omitting additional results that can be gleaned from the academic article, (1) scenario presentation dominates no scenarios, but (2) small-range scenarios dominate large-range ones.

Several senior executives we additionally interviewed reiterated the first result. As a reflection on the project team, “scenario presentation shows that at least the team has done quite a bit of work to get to know what the market is, how the product would behave in the market, and so on …” And, as far as the benefit to the project selection committee is concerned, “the advantage of scenarios is that it makes the project less uncertain; when I think of scenarios in a practical sense, it allows you [the decision-maker] to think how to overcome them [the problems].”

On the second result about the range of the scenarios, I quote yet another executive: “Sometimes, scenarios might mean that the team is not realistic; it might lead to a perception of the team not having made selections whether they want to start with the project.”

Thus, firms should help project teams present small rather than large-range scenarios. Small-range scenario presentation increases perceived team expertise and reduces perceived project risk. Large-range scenario presentation increases perceived project risk, and thus, may lead decision-makers to reject potentially promising innovation projects.

But our results also show that scenario presentation is more beneficial for transformational than for core projects, though here again with the limiting condition on their range. Hence, firms seeking to promote transformational innovation in their innovation pipeline should make the presentation of small-range scenarios required for pitches to project selection committees. This is relevant for 79% of surveyed firms that would like to select more transformational than core innovation projects and especially for the half of which that currently do not require scenario presentation!

Although the implication to present small-range scenarios may seem apparent, it is not evident in a sizeable number of firms where we observe that project teams present scenarios that are ‘too wide’ (57% in one of our studies). Our interviewees highlighted several reasons why project teams present large-range scenarios. For instance, some project teams may not be “focused enough” or may not do “strong pre-work to validate the assumptions of their project.” Project teams may also fail to collect sufficient information on potential customers, possible competitive actions, and major costs of maturing their project which are especially uncertain for transformational innovations, and thus, pose quite a challenge. What then can firms do? Practically, firms can take specific actions to encourage small-range scenario presentation, minimally by way of setting expectations, but additionally also by providing resources and training.

Put another way, firms should not neglect to invest in ways that improve their odds of selecting the best investments, critical innovation projects with the potential to define a firm’s competitive position chiefly among them.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Financial projections in innovation selection: the role of scenario presentation, expertise, and risk, by Vardan Avagyan, Nuno Camacho, Wim Van der Stede, and Stefan Stremersch, International Journal of Research in Marketing.

- The post expresses the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Skye Studios on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

This is a brilliant study. I think we know little about the role of information precision and scope in decision making for project management. This study offers an important practical insight to that regards. How managers obtain and process internal information for evaluating investment decisions of critical projects is a fundamental question of accounting and finance. Thank you for sharing.

Kind regards,

Anil