India has the third-largest startup ecosystem in the world, with over 60,000 startups and 65 unicorns (those that reach US$ 1 billion in valuation) in multiple industries. However, 90 per cent of these enterprises are likely to fail within the first five years, which makes it a difficult market to break into. Vipin Sreekumar, Priya Rachel David, and Palash Deb discuss the hidden pitfalls of the Indian startup market.

The pandemic has accelerated digital adoption by organisations worldwide, easing the flow of cross-border investments as investors can now quickly access information on foreign startups and their operating environments. As if in sync, overheated western markets, dominated by legacy investors such as Tiger Global, Andreessen Horowitz and Sequoia Capital, are sending startup deal valuations through the roof (The Economist, 2021). Many global investors are therefore exploring the large and booming startup markets in emerging economies, particularly China and India.

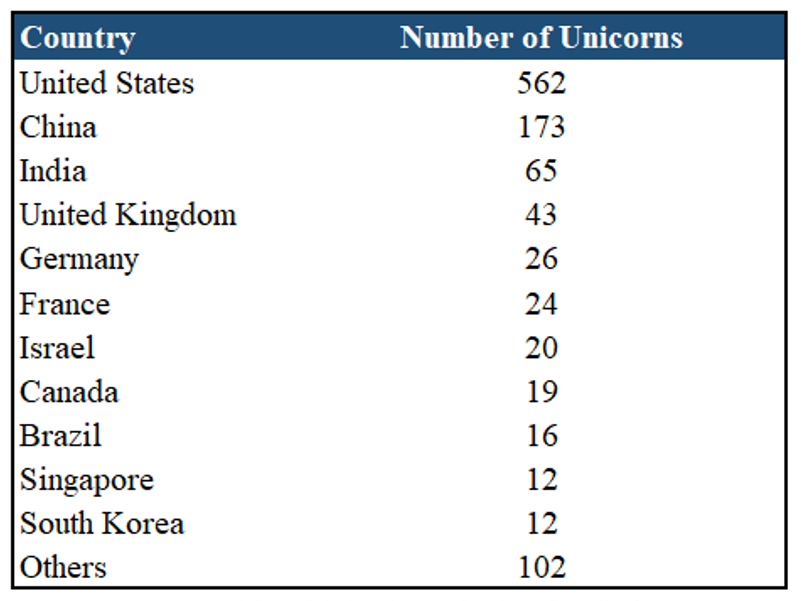

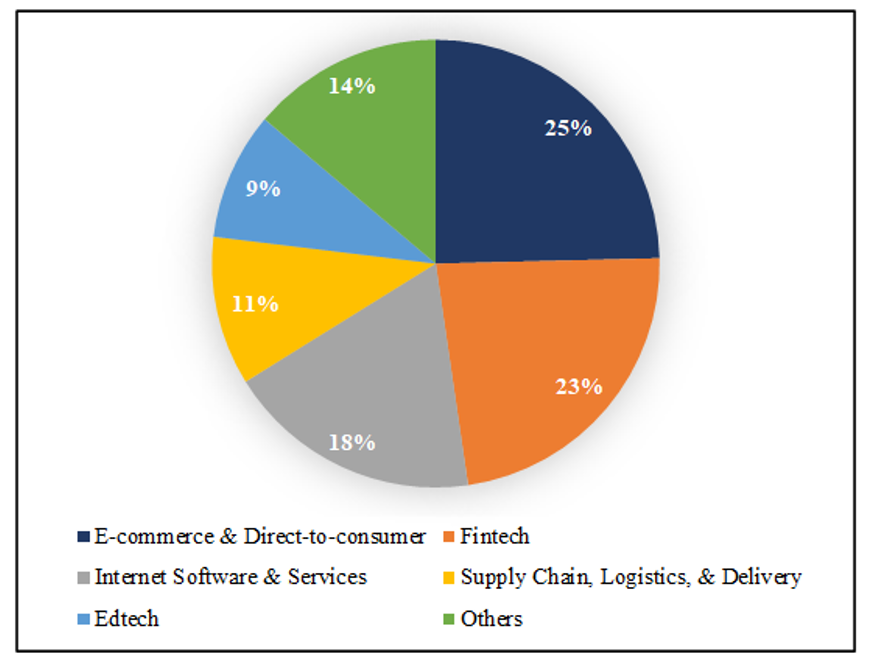

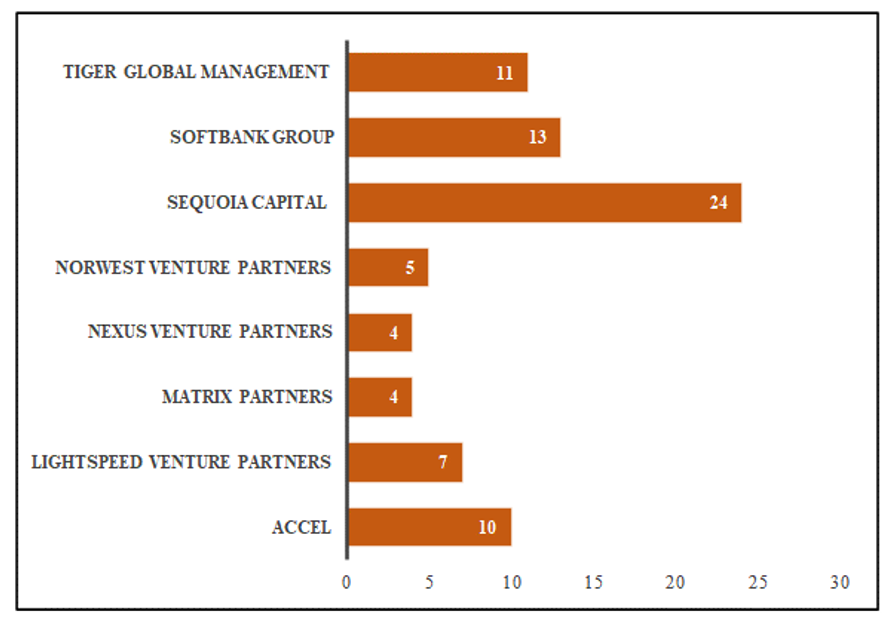

While much has been written about the many advantages of the Chinese startup scenario, the Indian startup scene appears equally promising, and needs deeper exploration. India has the third-largest startup ecosystem globally, with over 60,000 startups across its 642 districts. As of April 2022, India is home to as many as 65 unicorns across multiple industries, with money pouring in from major foreign investors (Table 1; Figures 1 and 2).

Table 1. Number of unicorns by country

Source: CB Insights Global Unicorn List (as of 6 April 2022)

Figure 1. Indian unicorns by industry (percentage)

Source: CB Insights Global Unicorn List (as of 6 April 2022)

Figure 2. Number of Indian unicorns funded by major foreign investors

Source: CB Insights Global Unicorn List (as of 6 April 2022)

But despite the optimism surrounding Indian startups, it is estimated that 90 per cent of them are likely to fail within the first five years. Global investors must therefore look for hidden pitfalls before they take the plunge.

Socio-cultural dissonance

Indian entrepreneurs differ from their western counterparts in how they view the world. For instance, the former are more reluctant to share information and take longer to trust outsiders (Harriss, 2003). There have also been cases of early-stage Indian startups splurging investors’ money (Rajagopalan and Zhang, 2008). This is in stark contrast to western countries where tighter socio-ethical norms motivate entrepreneurs to treat investors’ money perforce as their own. The recent allegations of financial impropriety against the founders of BharatPe, an Indian fintech startup, is a case in point. Besides, given the emphasis on close-knit family ties in Indian society (Warner, 2014), it is common for Indian startups to have family members in key leadership roles. Replacing them is never easy, implying that conflicts over governance issues may potentially arise in future if the Indian founding family is reluctant to cede any control even to investors with significant ownership stakes.

Misjudging the market and the customer

With a population of 1.4 billion, including a ‘middle class’ of around 600 million, India is said to have huge market potential. But this can be deceptive, given the much smaller de facto size of the Indian market. Take consumer technology, for example. According to a 2020 report by the Internet and Mobile Association of India, there are 622 million active internet users in India, but most of them possess only basic smartphones that lack processing speed and memory. Moreover, the absolute purchasing power of the Indian middle class is considerably lower than the middle class in developed economies (The Economist, 2018). Many Indian customers also distrust online transactions (Sahney et al., 2013), making it harder for geographically distant startups to attract these customers who often rely on traditional neighbourhood stores that accept cash payments. The Indian consumer is also highly price-sensitive (Mukherjee et al., 2012), making customer retention an ongoing challenge, and leading to cash burn in the form of discounts and deals.

Regulatory and other differences

Contrary to popular belief, it is not the lack of regulation that hurts Indian businesses, but over-regulation, which results in opaque administrative processes (India Economic Survey, 2021). Under-implementation, the flip side of over-regulation, is another common regulatory malady. Startups, in general, often create markets that are beyond the scope of the existing regulatory landscape (e.g., the lack of comprehensive regulations for self-driving vehicles), and this problem is worse in India. Indian startups also have to deal with regulatory flip-flops (The Economist, 2020). For instance, the recent revocation of the auto-payment feature for recurring payments by the Indian central bank caused major disruptions to payment wallets and other subscription-based startup models. What further muddies the water is that India is not one large, homogeneous market, but rather a collection of several micro-markets divided not only along the lines of state-specific regulations, but also by income levels, regional economic development, and cultural norms. These create a labyrinth of legal and other associated complexities that startups must navigate in order to thrive (David et al., 2021).

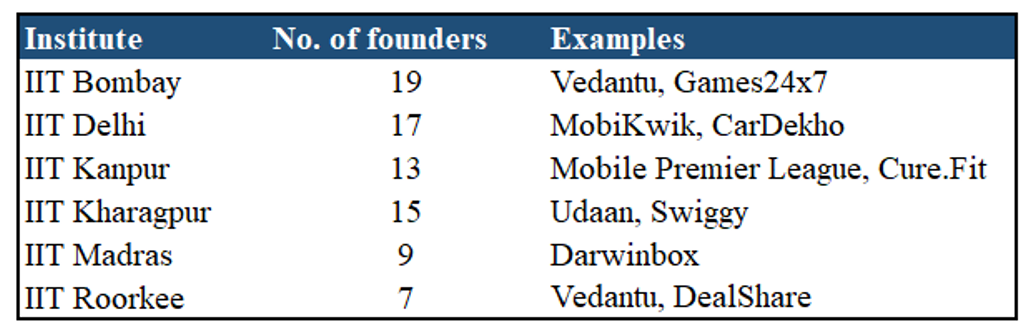

Thinking beyond Ivy League graduates

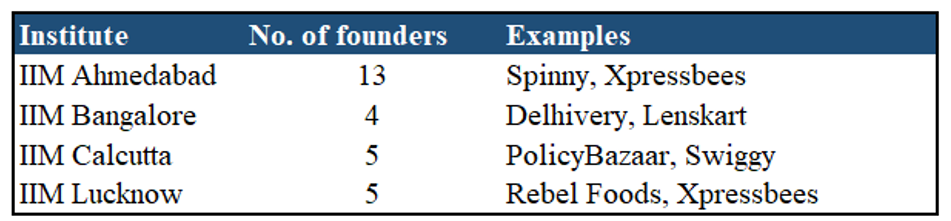

By and large, foreign investors have shown a preference for investing in startups founded by the alumni of the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) (Table 2) and/or the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) (Table 3), the Indian Ivy League universities (Nigam et al., 2020). However, viewing academic pedigree as a proxy for entrepreneurial ability can lead to poor investment decisions. Investors need to look beyond academic degrees while evaluating entrepreneurs, and discern more relevant signals such as social capital, technological competence, founding team experience, startup alliances, patent applications, access to government grants, or even affiliations with third parties or other venture capitalists (Colombo, 2021). Partnering with local incubators and accelerators can also be a good way for foreign investors to test the Indian startup waters.

Table 2. Number of Indian unicorn founders who are IIT alumni

Source: Adapted from the Hurun India Future Unicorn List 2021 and Tracxn

Table 3. Number of Indian unicorn founders who are IIM alumni

Source: Adapted from the Hurun India Future Unicorn List 2021 and Tracxn

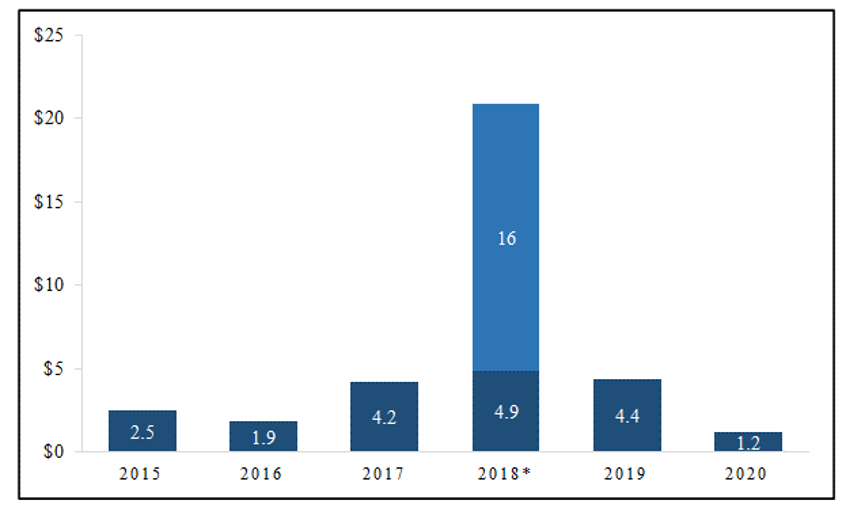

Figure 3. Total VC exits value in India ($B)

Note: The Walmart-Flipkart deal contributed approximately 80% ($16B) to 2018’s exit value. Source: Bain India Venture Capital Report 2021.

Exit costs

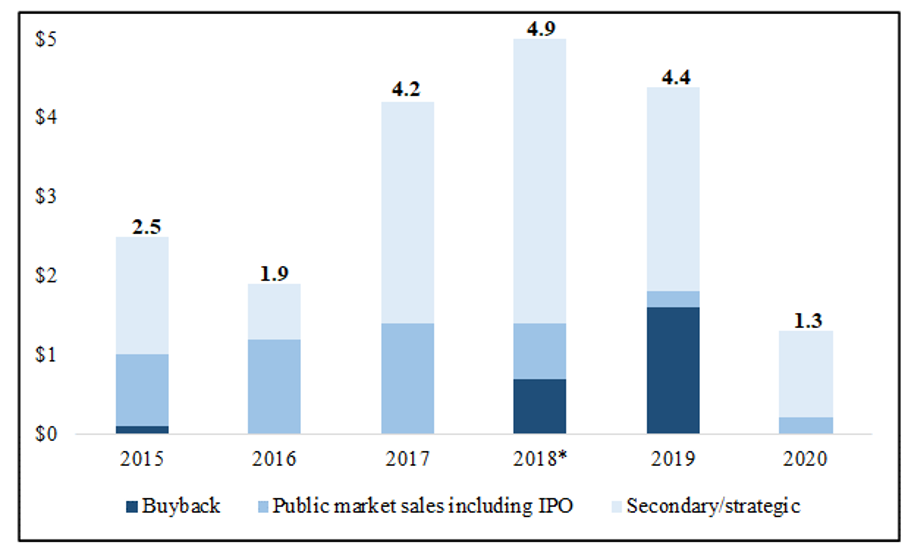

In the initial euphoria of investing in a promising startup, foreign investors must not forget to keep an exit door ajar. Exit can be tricky in the Indian market (Dominic and Gopalaswamy, 2019; Figure 3). Big-ticket acquisitions of startups, such as Walmart’s $16 billion acquisition of Flipkart in 2018, are rare. Most acquisitions do not result in high-value deals, with many startups “marked to myth” rather than to market (The Economist, 2020). Pulling off a successful IPO is no easy feat either (Figure 4). Despite the spate of IPOs in 2021 (examples include digital payment giant Paytm, food delivery company Zomato and the cosmetic e-tailer Nykaa) and the relaxation of norms by SEBI (India’s capital market regulator), the number of startups going public is still quite low when compared to the US or China. That is because the Indian capital market is still relatively underdeveloped, with a somewhat lukewarm participation by retail investors (Giannetti and Koskinen, 2010). Post successful listing, the market prices of many newly listed stocks often witness a sharp decline, causing retail investors to question their massive valuations. This has forced many startups to reconsider their IPO plans, making it even harder for investors to find a profitable exit.

Figure 4. VC exits in India by mode of exit ($B)

Note: Excluding the Walmart-Flipkart deal. Source: Bain India Venture Capital Report 2021.

Figure 5. Investment in Indian startups between 2014-2020 ($B)

Source: Inc42+ The State of Indian Start-up Ecosystem Report 2021

The Indian startup ecosystem continues to grow at a rapid clip, with overall funding touching $70 billion during 2014-20 (Inc42, 2021; Figure 5). But despite the optimism, running a successful startup in India remains a daunting challenge. Foreign investors, in particular, must understand how and where they can go wrong when investing in India.

♣♣♣

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not those of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Featured image by Sanket Shah on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

India is growing in a silent way.

I think in the next few decades India will be one of the economic hubs of the world.

Interesting article. However, some of your facts are outdated and quoted totally out of context or any frame of reference.

Your headline grab: “However, 90 per cent of these enterprises are likely to fail within the first five years, which makes it a difficult market to break into.” – this refers to an IBM Institute for Business Value whitepaper, which in-turn refers to a blog on NDTV.com that is dated March 2017 – your article is dated May 2022!!

The entire relevance of your article is questionable – since the very premise seems faulty. Further, apart from the one reference to the IBM whitepaper, there is really nothing in your article that goes to support your headline grab that “90% of Indian startups will fail within 5 years!”

Let’s take a look at some FACTS.

– In 2017, there were about 4,000 startups in India (in total) – https://www.statista.com/statistics/691887/number-startups-in-india-by-vertical/

– If one were to assume that the NDTV Blog, IBM Whitepaper, and your blog were true, then the Indian startup ecosystem should be practically dead! Instead you now have 66,000 + startups in India (2022 data).

– You report statistics are with a 2020 outer range, despite the fact that you write this article in 2022!! The COVID impact has in fact triggered the rise of startups in India, and this trend is only going to increase in the years to come. Funding scenarios WILL undergo ups and downs – that’s normal with any economic cycle in any country. India is not unique to this. The Ukraine war has stalled a lot of initiatives across geographies, industries and companies (in various stages of growth and existence). But this is a blip in the larger scheme of things. Not a barometer by which you can set forth an opinion.

– Your conclusion leaves me mystified! “But despite the optimism, running a successful startup in India remains a daunting challenge. Foreign investors, in particular, must understand how and where they can go wrong when investing in India.” – what is the basis of this opinion? Nothing in your article goes to contribute to this conclusion with any specific reference to India.

– IPO’s failing is due to the forced exits that PE’s need – to showcase returns to their Limited Partners. I can’t think of a single sane Founder who wants to exit at the detriment of the investing public. By the time the startup gets to the stage of an IPO, the founders are highly diluted – the only real beneficiaries are the PEs. And SEBI norms with regard to a track record of profitability has vanished – leaving the doors open for loss making startups to launch an IPO.

Anyways, I think I have made my point. This is a highly respectable blog space of LSE, and I would reckon that a little more caution, a little more diligence is the norm rather than the exception.

Cheers,

Ananth