Six years on from the EU referendum, can we know for certain that Brexit, not COVID, had a negative impact on the UK economy? Michael Ellington, Marcin Michalski, and Costas Milas attempt to separate the impacts of both events and find that Brexit had a contractionary impact on UK GDP growth, with significant spillovers to UK financial markets in the form of rising long-term borrowing costs and increased exchange rate volatility.

Six years have just gone since the EU referendum initiated the UK’s exit from the European Union. Yet, as George Parker and Chris Giles from The Financial Times emphatically note, there is very little appetite among Eurosceptic or Europhile parties to debate the positives or negatives from the UK’s decision to break ranks with the EU. And yet, as David Smith (Economics Editor of The Sunday Times) notes, “we have paradoxically become more European, with higher sustained levels of public spending and the tax burden heading for its highest since the late 1940s”.

Also notice the ongoing silence on what impact Brexit is already having on the UK economy. In fact, Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak both insist that, as things stand, there is no easy way to try to separate the economic impact of Brexit from the one coming from the ongoing COVID-19 shock. If anything, it makes sense to argue that COVID-19 is…conveniently “hiding” the true impact of Brexit on the UK economy.

This does not need to be the case. In brand new (and peer-reviewed by as many as three anonymous referees!) research, we attempt to separate the impacts of Brexit and COVID-19 on the UK economy. Using monthly data between January 2000 and January 2021, we monitor developments in the UK economy through the lenses of 12-month gross domestic product (GDP) growth. Rather than relying on the Bank of England’s Bank Rate as our main monetary policy instrument, we focus on Divisia money growth. This very choice of ours is dictated by earlier research which shows empirically and theoretically that the Divisia money feasibly acts as a monetary policy variable. Divisia money captures monetary policy stance when interest rates approach their effective lower bound. In fact, academic research has found that Divisia money is a powerful predictor of GDP growth both in the US and the UK.

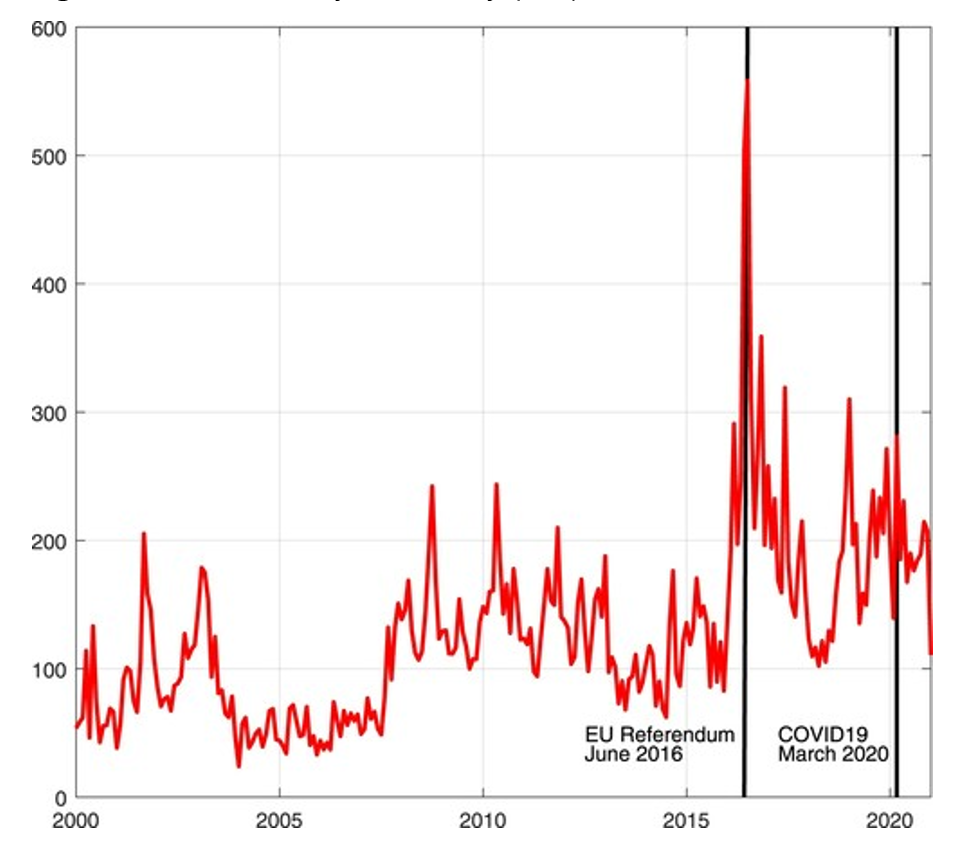

For Brexit-related purposes, our main interest lies with economic policy uncertainty (EPU) and financial stress conditions in the UK. The EPU index picks up keywords relating to economic policy uncertainty from major newspapers in the UK. We plot the UK’s economic policy uncertainty index in Figure 1. Following the decision to leave the EU on 23 June 2016, the UK’s EPU index peaks in July 2016 at an all-time high of 558.22 points. These high levels of EPU persist until early 2018 before rising again and remaining high until the end of 2020 when the UK left the EU. The dynamics of the EPU index during the period we study conform with the view that the Brexit referendum has been by far the most significant event so far in the post-war British political history and are an accurate representation of the volatile nature of the negotiations in the UK’s future relationship with the bloc that took place between 2017 and 2020.

Figure 1. Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) in the UK

Source: Economic Policy Uncertainty is available here.

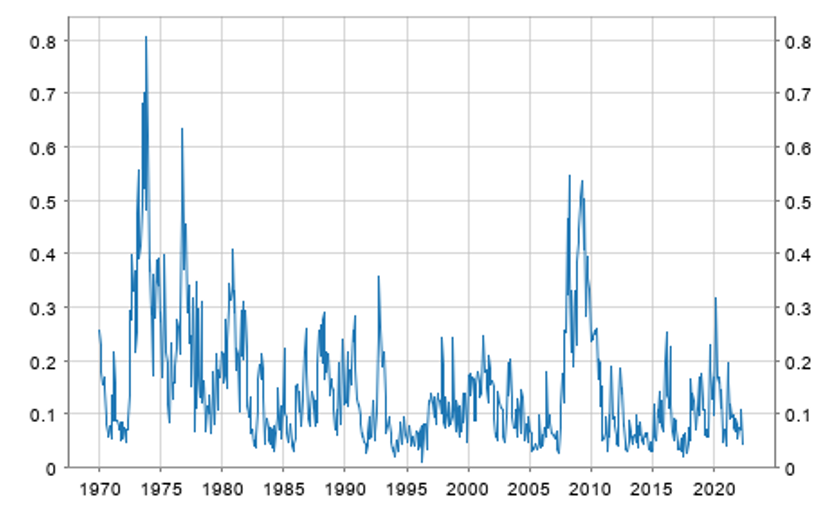

Our UK financial stress index is provided by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) historical database. The stress index pools information on the volatility of (i) the real effective exchange rate; (ii) the equity market; and (iii) the bond market (using the volatility of the 10-year government bond yield). Although the stress index rose significantly around the EU referendum date, its rise at that time was less elevated compared to early 2020 when COVID-19 triggered the first lockdown in the UK.

Figure 2. UK financial stress index

Source: UK financial stress is available here.

Under the assumption that economic policy uncertainty is closely related to the EU referendum result, we simulate the impact of an economic policy uncertainty shock on the UK economy. Our main findings are as follows:

- An economic policy uncertainty shock triggers a statistically significant and contractionary impact on UK GDP growth for as many as twelve months. In fact, and this is very important, we find that such contractionary effect can only be identified if the outliers in macroeconomic and financial data brought by the COVID-19 pandemic are appropriately accounted for in our empirical model which uses sophisticated econometric methods proposed only recently by economists Michele Lenza and Giorgio Primiceri.

- The above-mentioned economic policy uncertainty shock spills over to UK financial markets in terms of higher financial stress, mainly in terms of rising long-term borrowing costs and increased volatility in the sterling exchange rate. These unwelcome developments in UK financial markets generate additional contractionary effects which last for as many as twenty months.

These are short- to medium-term implications of Brexit and complement recent work by the Bank of England on the long-term implications of Brexit. Following the signing of the Trade and Co-operation Agreement between the UK and the EU, the Bank of England estimated that in the long term UK trade will be 10.5% lower, and productivity and GDP will be 3.25% lower under the agreement, relative to a frictionless arrangement. Other work by The Centre for European Reform uses the ‘doppelgänger approach’. The approach looks at the average performance of advanced economies similar to the UK, but which did not have Brexit to find that the UK economy was, at the end of 2021, 5.2% smaller because of Brexit.

Our main findings have implications for the so called Northern Ireland Protocol Bill. The Bill has already created tensions between Johnson’s government and the EU and has triggered serious accusations that the UK is about to breach international law. Our belief is that by pushing forward with this very bill, Johnson’s government will unnecessarily add to existing economic policy uncertainty. Indeed, how many counties around the world will be willing to sign trade agreements with the UK when Johnson’s government has been accused of breaching international law? This will fuel economic policy uncertainty but also hit the country’s trustworthiness in international markets therefore increasing the interest rate that investors demand to bring, or even keep, their money in the UK. As our work has shown, rising economic policy uncertainty and higher interest rates feeding into elevated financial stress will create the “perfect” conditions for further recessionary effects in the UK economy over and above the recession currently predicted by the Bank of England. Notice that the Bank of England’s econometric models have accounted for the adverse economic impact of rising inflation on UK real incomes and the war in Ukraine but not for the “unpleasant” developments regarding the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Of votes and viruses: the UK economy and economic policy uncertainty, The European Journal of Finance, June 2022

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Ed Robertson on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

1 Comments