When facing a crisis, leaders need to take a thoughtful, positive, resilient, and transformative approach to crisis management. However, they often do the opposite, denying and minimising the problem, or reactively taking action that escalates the situation. Sarah Kovoor-Misra describes four key capabilities that can help organisations not only prevent or quickly contain damage, but strengthen trust, gain new insights, and emerge with capacities that can help them cope more effectively with future crises and challenges.

One of the challenges for leaders when faced with a crisis is that there is a tendency to deny and minimise it, or reactively take action that often escalates the situation. These tendencies were evident in the Volkswagen defeat device and the Wells Fargo fraudulent bank account crises, where leaders first turned a blind eye and took on a defensive posture.

In my book, I suggest that leaders can instead choose to take a thoughtful, positive, resilient, and transformative approach to crisis management. Through this approach, they can not only prevent or quickly contain damage, but the organisation and its key stakeholders can strengthen trust, gain new insights, and emerge with capacities that can help them cope with future crises and other challenges more effectively.

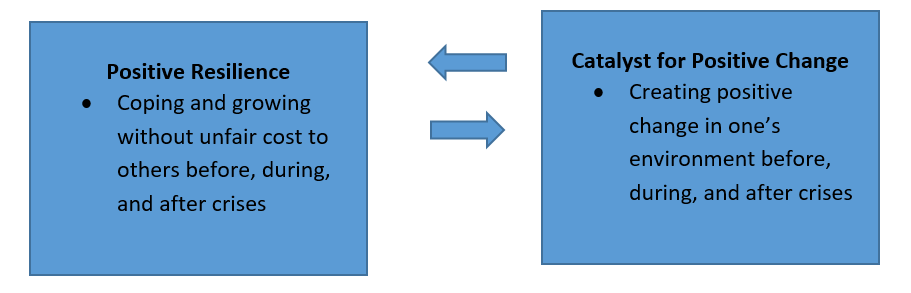

Positive resilience is the ability to overcome challenges without taking unfair advantage of others. Creating a defeat device in the Volkswagen crises or opening fraudulent bank accounts by Wells Fargo employees are examples of negative resilience. This latter form of resilience solves problems in the short term but eventually results in crises for most organisations. Instead, positive resilience enables organisations to solve problems without compromising their reputation and brand. In addition, when leaders and their organisations are transformative, they are not only overcoming challenges but are catalysts for positive change in their environments. Resilience enables leaders and others to be transformative, as it gives them the confidence to think beyond themselves. In turn, the experience of being transformative reinforces their confidence. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. The nature of being transformative during crisis management

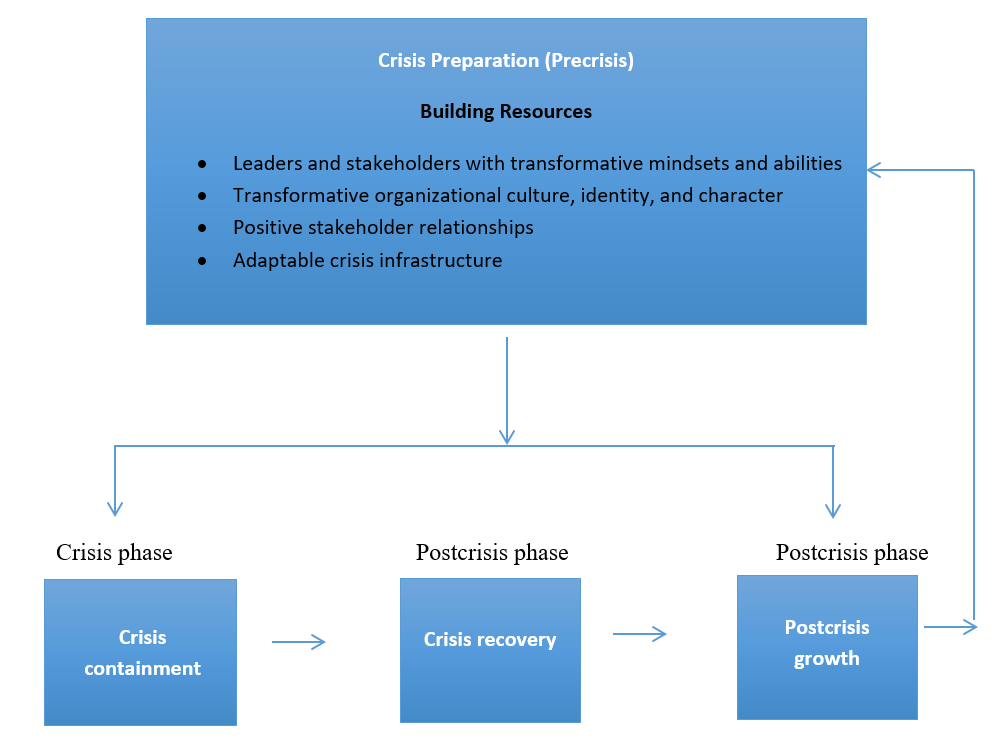

A positive resilient and transformative approach during a crisis and in its aftermath requires four key capabilities. These capacities can be built prior to a crisis, can be further developed as leaders think on their feet during a crisis, and from lessons learned after a crisis. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Phases of a transformative crisis management approach

These four capacities are:

- Leaders and stakeholders with transformative mindsets and abilities. A transformative mindset is comprised of beliefs, values, and traits that support courage, excellence, innovation, and integrity during crisis management. In addition, it requires multiple forms of intelligence to be able to navigate the cognitive, emotional, political, relational, and moral complexities and minefields associated with a crisis. For example, the Taj Mahal Palace hotel had taken the initiative to hire and train leaders and other employees with these capacities, and this enabled them to be resilient, innovative, and transformative when they were attacked by terrorists in 2008. Their employees kept guests calm, helped many escape, and reduced the loss of lives.

- Organisational culture, identity, and character. Transformative values and traits, such as relationship orientation, integrity, courage, hope (RICH), resilience, innovation, social responsibility, excellence, and nonstop learning (RISEN) also need to be a part of the organisation’s culture, identity, and character. The organisational culture is the shared beliefs and values that inform employees as to how to behave. The organisational identity consists of the core traits that defines the organisation for its members. Finally, the organisational character is formed by the defining moral beliefs and traits of the organisation. These beliefs, values, and traits guide behaviour during crisis management. For instance, prior to the 1982 Tylenol crisis, leaders at Johnson & Johnson had defined a credo and built these resilient and transformative components into the organisation and it enabled them to be skilful during the crisis.

- Positive stakeholder relationships: Organisations with a network of positive relationships that include employees, customers, investors, suppliers, community members, and relevant governmental agencies have access to resources, such as information, support, and goodwill during crisis management. For example, during the Boston Marathon terrorist attack of 2013, a network of stakeholders, such as various governmental agencies and the general public, were instrumental in finding the perpetrators and containing the crisis.

- Adaptable infrastructure: Having in place well trained crisis management teams who have previously strategised and devised crisis plans and who have access to necessary resources can enable leaders to be agile and skilful during a crisis. For instance, in the Boston Marathon crisis, the prior preparedness of various governmental agencies in terms of handling an improvised explosive device enabled them to coordinate effectively with each other and quickly contain the crisis. Crisis plans and teams, however, need to take a multidimensional approach and address not only obvious operational issues, but also address the psychosocial damage from the crisis.

It is not possible for leaders to have considered every eventuality prior to a crisis. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic took most organisations by surprise. In these situations, the above four capacities can be critical as they can enable leaders and their organisations to improvise and respond quickly within well understood boundaries of morality, as they face the novelty and ambiguity of new forms of crises.

To be able to build resilience and transformative capacity within organisations also requires awareness. In my book, I provide some tools to enable organisations to assess their capacity and identify areas for change. For instance, individuals can evaluate their task, relationship, and self-management capacities, or leaders can assess their organisations’ transformative values and traits, and the extent to which they have built positive stakeholder relationships and adaptable infrastructure.

To conclude, effective crisis management requires leaders to accept that both predictable and new forms of crises can threaten their organisations. They therefore need to invest time and resources in building resilient and transformative capacities within themselves and their organisational systems. In addition, when a crisis hits, they need to stay calm, be thoughtful, and use these capacities so that they can take a positive, resilient, and a transformative approach. The reward for these efforts can be high and result in positive outcomes, such as damage being minimised, strengthened stakeholder trust, an enhanced brand, pride amongst employees toward the organisation, and new insights and knowledge.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the author’s book Crisis Management: Resilience and Change, SAGE.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Adrien Delforge on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.