Since 2021 Italy has experienced a significant growth in inward foreign investment, outpacing other EU economies. Annual inflows of new greenfield foreign direct investment (the construction of brand-new subsidiaries as opposed to acquisitions of existing companies) have grown by 33%. Inward cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&As) increased by 14%, and inflows of venture capital and private equity by 250% and 50%, respectively. Riccardo Crescenzi and Sebastiano Comotti write that, along with the structural reforms underway, the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) has played a key role in the recovery. They recommend a cautious approach to any future re-negotiation of the plan by the Meloni government.

The context

In a context of global investment flow stagnation and generalised re-organisation of supply chains, the pandemic has exacerbated geo-political tensions and conflicts. This has increased global competition for the attraction of foreign direct investment (FDI) the world over. The European Union has responded to these challenges with an unprecedented shift in economic policy, mobilising significant resources for recovery through its NextGenerationEU programme and National Recovery and Resilience Plans (NRRPs). Italy – the largest beneficiary of EU recovery funds and a key experimentation field for the associated reforms – has historically punched below its weight in terms of FDI attraction. However, a recent LSE study suggests that the appetite of global investors for the Italian economy might be on the rise (at least temporarily), shedding some positive light on the opportunities generated by recovery policies in Europe.

A shift in incoming foreign capital flows

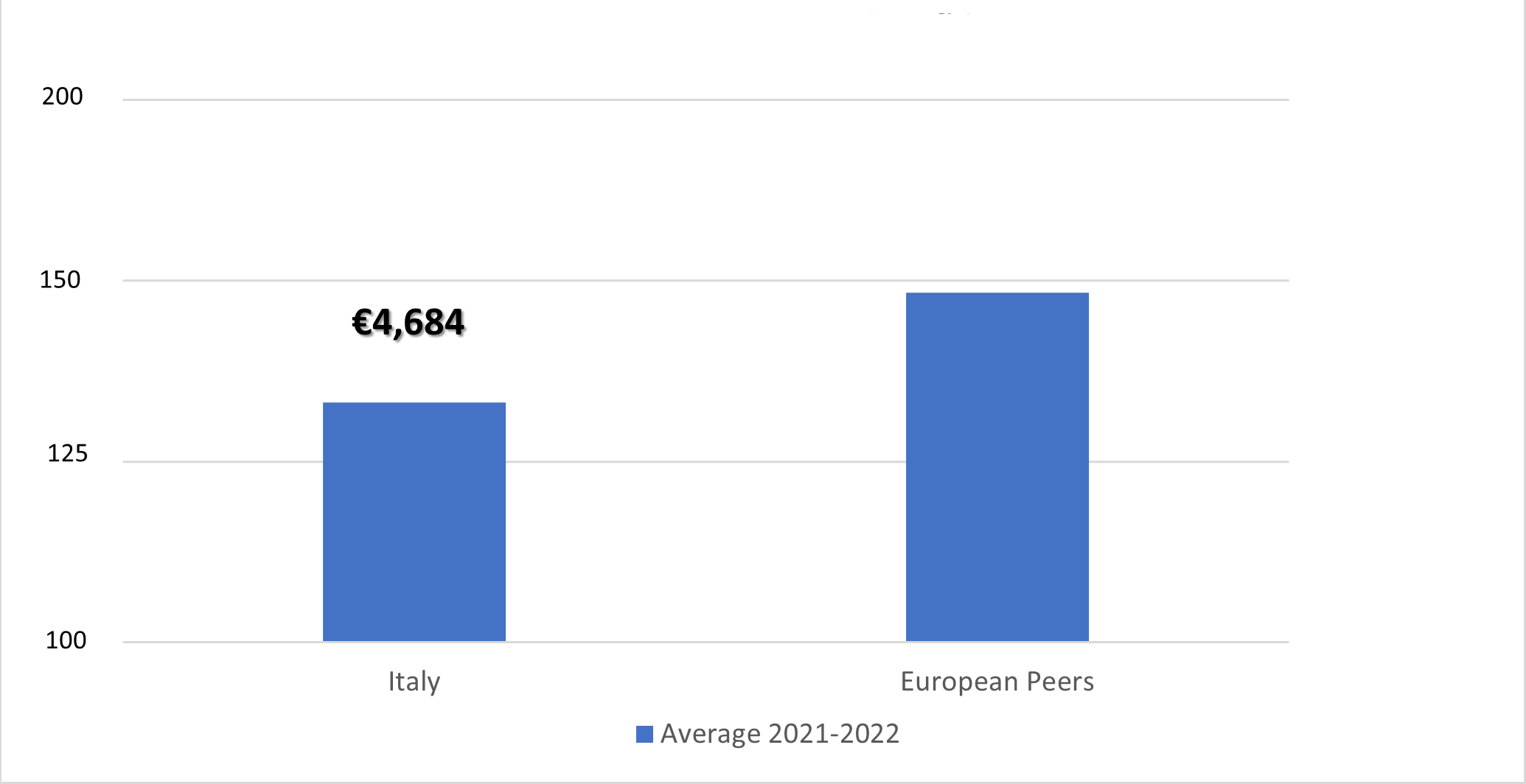

In 2021, according to OECD data, average FDI inflows in OECD countries bounced back to their pre-pandemic (2013-2019) levels, with a further upward trend in the first quarter of 2022 (21% increase in Q1 2022 compared to Q1 2021). Our study shows that Italy has significantly exceeded its average annual pre-pandemic inward FDI performance, recording a 33% increase in greenfield FDI projects (Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Inward FDI, greenfield investment. Comparison of average annual capital invested for 2013-19 (=100) and 2021-22**

Source: BVD Orbis Crossborder Investment. Notes: The group of ‘European Peer’ used as a benchmark includes France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain. The value reported is an unweighted average. Data for Germany are still provisional and to be verified by the data provider. ** Information for 2022 has been estimated and projected to annual values based on FDI project data for Q1 & Q2 2022. The estimated annual average value of FDI inflows for 2021-2022 in Italy is 4,684 million euros and 16,753 million euros for its European Peers as listed above.

In 2021, the interest of foreign investors in the acquisition of Italian companies exceeded pre-pandemic levels. Overall, Italy has a significantly stronger post-pandemic net position than other similar EU economies, with a 14% growth in inward cross-border M&A deals. Italian companies have also been very active in domestic transactions (internal consolidations) and some major acquisitions of firms in foreign countries (i.e., outward cross-border M&A, e.g., Stellantis, Luxottica).

Invest Europe data suggest that private equity and venture capital firms invested €138 billion in European companies in 2021, a 61% increase vis-à-vis the annual average in 2017-2019. In post-pandemic Italy, foreign capital inflows have grown substantially vis-à-vis other European economies. Annual inflows increased 250% for private equity funds and 50% for venture capital in 2021.

Key signals

Greenfield FDI implies the construction of brand-new subsidiaries of foreign companies in the host economy, generating additional jobs that do not necessarily materialise in the case of foreign acquisitions of existing domestic companies. By looking at these flows it is possible to capture some changes in the appeal of the Italian economy to productive investors.

Data show a significant rebound of sectors linked with the end of mobility restrictions and the recovery of tourism (i.e., ‘hotels’ and ‘passenger air transport’) as well as ‘retail’ and ‘warehousing’. There is also an upward trend in three key sectors associated with the priorities of the Italian National Resilience and Recovery Plan: ‘energy’, ‘automotive’, and ‘pharmaceutical’. At the same time, ‘research and experimental development’ and ‘data processing and hosting’ are part of the top ten sectors in terms of the absolute value of the investments in the post-pandemic phase, even if they have not fully recovered to pre-pandemic levels

The origin of inward greenfield FDI to Italy is centred in Europe and North America. The importance of Europe as a source of greenfield investment has grown after the pandemic, in line with a possible trend of reinforcement of European value chains. Within the EU, Spain plays a growing role. Brexit seems to have only marginally affected UK investment in Italy. At the same time, the consolidation of the role of China (and Asia more generally) is visible but the centrality of the US remains undisputed.

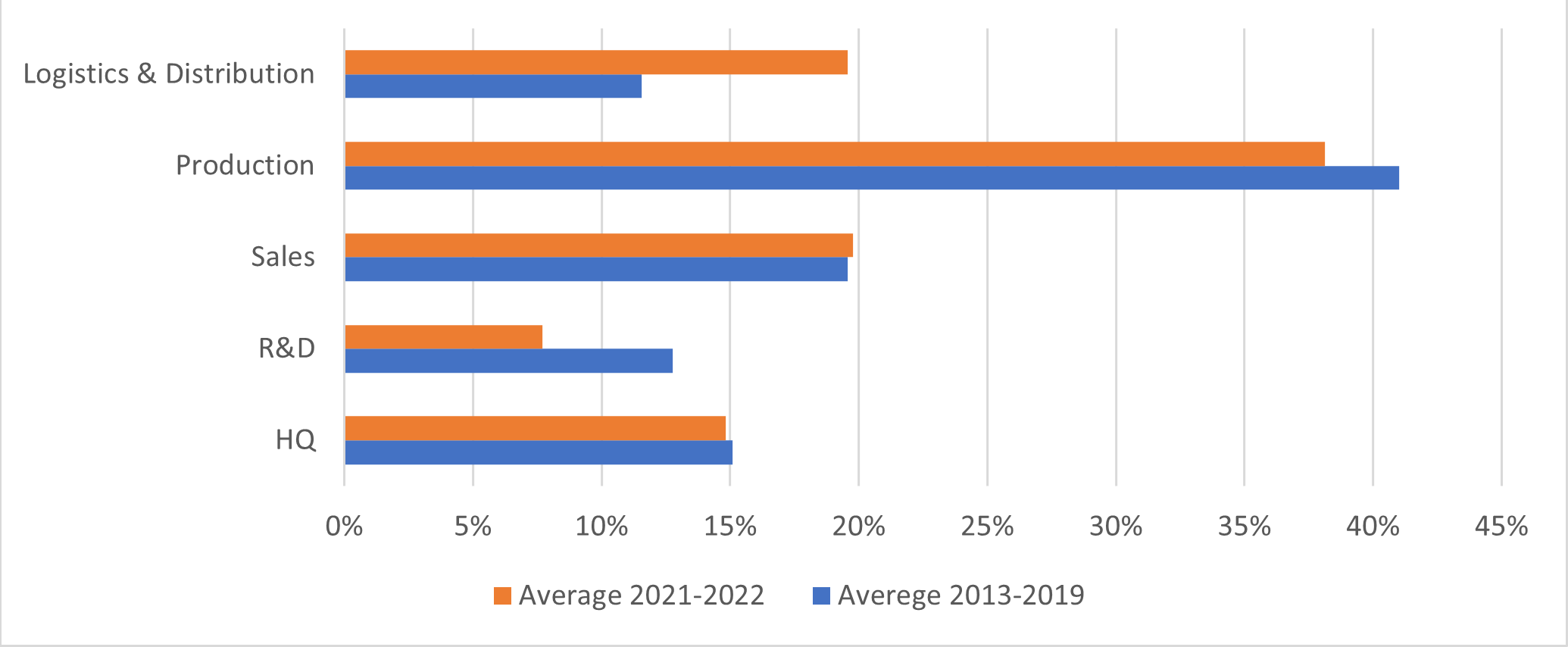

The classification in ‘global value chain’ stages looks at the position of each new foreign investment project along the value chain, ranging from R&D and product design to production and then sales and distribution, cutting across sectors and focusing on functions.. The ‘smile curve’ of value creation suggests that most of the value added is generated by activities at the initial stage (e.g., R&D, design) and the final one (e.g., marketing), with production becoming gradually less important.

The analysis of new greenfield investment projects suggests that inward FDI in Italy is moving downstream with more activity in logistics and distribution than before the pandemic, at the expense, at least in the short-run recovery stage, of production and more upstream ‘R&D’ activities (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2. Greenfield inward FDI in Italy, global value chain stages by capital invested. Average shares 2013-2019 vs 2021-2022

Source: BVD Orbis Crossborder Investment. Note: Data for 2022 cover Q1 & Q2 – Classification of FDI projects in ‘GVC stages’ based on Crescenzi et al. 2014. The classification excludes some business functions that cannot be univocally linked with a GVC stage: Entertainment, Agriculture, Banking & Finance, Commercial Real Estate, Health, Hotels, Residential Real Estate, Utilities.

An uncertain future

Italy has still significant room for growth in comparison with other EU economies. The country is in a position for growth in American and Asian FDI due to possible onshoring/re-shoring adjustments catalysed by geopolitical factors. Growth opportunities are also emerging within the EU, given the pressure for the development of European value chains. The National Recovery and Resilience plan has apparently been able to ‘signal’ to foreign investors that ‘Italy is open for business’.

However, the significant post-pandemic dynamism is challenged by difficult global economic conditions in the rest of 2022. At this important turning point for Italy’s internationalisation trajectory, it is key to:

- Maintain momentum on reforms.

- Consolidate stability and regulatory certainty, especially with respect to digital markets.

- Focus on ‘quality’ FDI with an emphasis on those that can offer opportunities to link up to Global Value Chains and upgrade.

- Also consider actions for active internationalisation and trade in a systematic manner (coordination).

- Maintain focus on R&D and innovation, with coordinated policies for domestic eco-systems.

- Work on targeted investment promotion consistent with the priorities of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP).

However, what remains to be seen is what approach the new government will take regarding the EU Recovery and Resilience Plan and to internationalisation policies. Urgent work is needed in order to evaluate the impacts of existing tools and policies and support the design of evidence-based interventions (e.g., How effective are current investment promotion efforts in different NRRP priority areas? How to improve impacts and returns on investment?). The goal must be to increase opportunities for growth-enhancing foreign investment. This should be the key priority (and also the challenge) for the new Italian government as well as for the EU. When it comes to the success of the Recovery Plans on the ground and the long-term prosperity of the Italian economy, it is important to keep the current window of opportunity open and possibly to further extend it with consistent evidence-based interventions. Therefore, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni needs to take a very cautious and evidence-based approach to any request to re-negotiate with the EU the current structure and terms of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, resisting the many internal pressures in her own party and coalition.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Inward FDI in Italy: some recent trends.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Michele Bitetto on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.