Recent HMRC statistics show a fall in the number of non-domiciled residents (non-doms) in the UK—people living in the country who benefit from generous tax exemptions on their foreign assets and investment returns. The number has fallen not because non-doms have left, but because they stopped claiming, write Arun Advani and David Burgherr. Misinterpretation of these statistics, and of the policy more generally, risks leaving the UK with a policy that is costly, unfair, and bad for growth.

Tax breaks for the rich dominate the headlines, especially since the previous government announced the abolition of the additional rate of income tax in its infamous “mini-budget” in September. In the end, the additional rate survived, the government did not.

A recent article in the Telegraph warns that “punishing tax changes” are driving away the ultra-wealthy from the UK, pointing to the apparent drop in the number of non-doms since 2015. But the claims in the article are not supported by the evidence.

Restrictions to the non-dom regime have led to minimal emigration

The article rightly observes that the rules of the non-dom regime have been tightened gradually since 2008. But its interpretation of HMRC’s statistics on non-doms is incorrect.

HMRC’s own commentary on these statistics notes that the post-2017 drop in the number of non-doms, and the tax they pay, is due to a fall in people claiming the status – as required by the reform – rather than emigration.

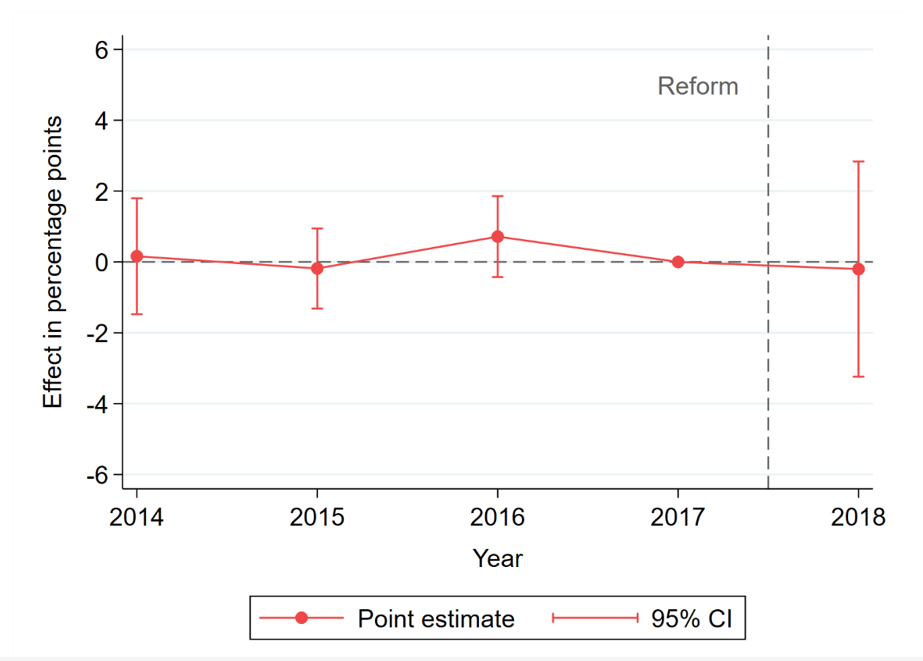

Our own work shows that non-doms who lost access to the tax break were no more likely to leave the UK than those still benefitting (Figure 1). In fact, both our research and HMRC analysis suggest that the 2017 reform has boosted revenue collected without triggering an exodus.

Figure 1. Migration response to the deemed domicile reform in 2017-18

Notes: Dynamic difference-in-differences estimates showing the effect of losing access to the remittance basis on UK residency, exploiting Condition B of the deemed domicile reform. The graph displays year-specific effects relative to pre-reform tax year 2016-17 and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Treatment group includes individuals who have been UK resident for 15–19 of the previous 20 years. Control group includes those who have been UK resident for 12–14 years over the same period. See Advani, Burgherr, and Summers (2022a) for details of the empirical approach. Source: Authors’ calculations based on HMRC administrative datasets.

The current regime is deeply flawed

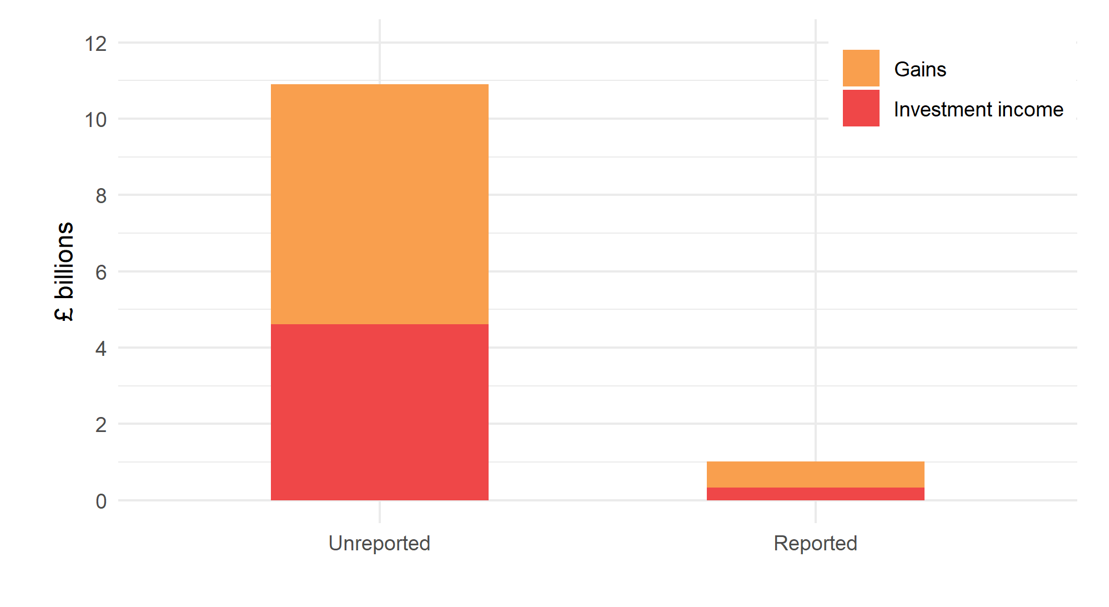

We agree that Britain should aim to attract and retain talent and investment. But the non-dom regime does precisely the opposite. First, it is only available to foreigners who plan to return home. People coming to the UK to settle here indefinitely are not eligible. Second, it only provides a tax break to those who have substantial wealth already. Highly skilled young migrants receive little benefit from tax breaks based on existing wealth. Third, it encourages the wealthy to invest their money anywhere but the UK, because they must pay tax on returns on investments made here, while foreign returns are exempt. Unsurprisingly, non-doms keep the bulk of their investments overseas: we estimate that they have over ten times more foreign investment income and capital gains than they report to HMRC (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Aggregate investment income and gains of remittance basis users, unreported and reported, 2018

Notes: Remittance basis users are non-doms who make a formal claim for the remittance basis on their tax return and report having at least £2,000 in unremitted income. Under the remittance basis, foreign-source investment income and capital gains are exempted from UK tax unless they are brought into the country. Remitted foreign-source investment income and gains are included in reported income. Offshore income and gains are estimated based on the information of UK doms with similar characteristics (see Advani, Burgherr, and Summers, 2022b). Reported income and gains are directly observed in the administrative tax data. Source: Authors’ calculations based on HMRC administrative datasets.

And on top of the cost of investments not made, the current regime costs us £3.6 billion per year in lost income tax and capital gains revenue, after uprating our previous analysis to 2022.

Contrary to popular belief, the regime encourages non-doms to even do their shopping overseas. The law explicitly allows them to spend their untaxed foreign income and gains on clothes, shoes, jewellery, and watches abroad, and bring these goods into the UK without incurring a tax charge. Given these incentives, who would be foolish enough to remit their money to the UK where it is taxed before they can spend it at Harrods?

The case for reform

A serious reform of non-doms policy could therefore boost growth as well as the tax take. Instead of handing out poorly designed tax breaks based on a flawed reading of the evidence, we should welcome the wealthy to the UK while giving them the right incentives to contribute to the economy and the public coffers.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Jurica Koletić on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.