Careers evolve throughout workers’ life cycle, but what exactly leads to wage growth? Jérôme Adda and Christian Dustmann use a comprehensive framework that looks at apprenticeships, job mobility, and other factors, and analyse how they contribute to wage growth in workers’ careers.

Understanding how workers’ careers evolve throughout their life cycle and how their early educational decisions impact wage growth are crucial questions for economists and policymakers. These questions are essential for evaluating earnings inequality, overall economic productivity, and citizens’ wealth (Lucas et al., 2016).

Earlier economic studies have emphasised the significance of human capital, search capital, and worker mobility across firms as essential drivers of wage growth (see, e.g., Becker, 1994; Mincer, 1974; Ben-Porath, 1967; Killingsworth, 1982). Recent research has highlighted the importance of worker selection across sectors with different task requirements based on innate abilities (e.g., Autor et al. 2003). Additionally, workers’ career choices may be influenced by non-pecuniary factors such as working conditions and commuting distances. Le Barbanchon et al. (2019) have explored this idea further.

Wage growth over the life cycle

Our new paper (Adda and Dustmann, 2023) presents a comprehensive framework for analysing the different factors that contribute to wage growth in workers’ careers. We use longitudinal administrative data from Germany to track workers over up to thirty years. The study focuses on workers entering the labour market directly after completing secondary school or enrolling in apprenticeship training programs. We also examine the types of jobs workers choose, broadly categorised as routine-manual jobs requiring repetitive tasks or cognitive abstract jobs requiring more complex cognitive and abstract skills. The study also considers both monetary and non-monetary job characteristics, such as flexibility or location, which influence workers’ job choices.

Apprenticeship training

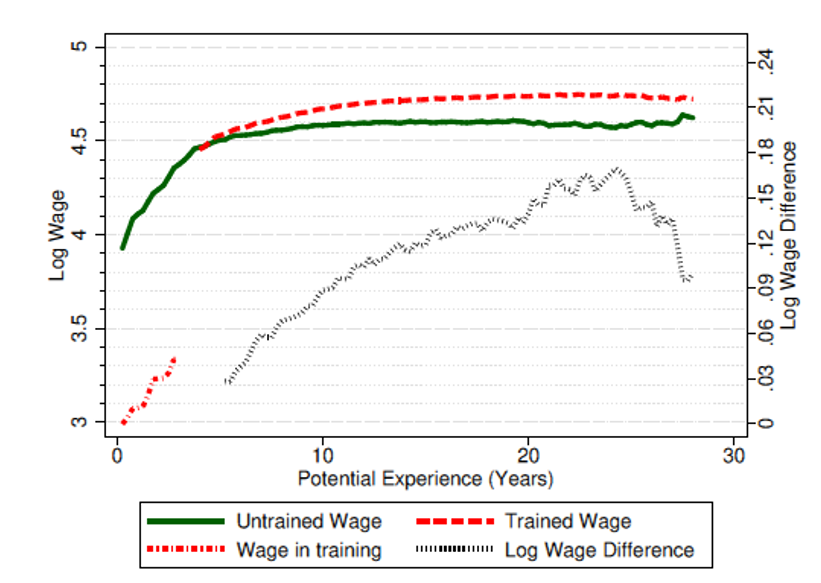

The data in Figure 1 compares the wage growth of workers who underwent apprenticeship training before entering the labour market to those who did not receive any further training. The wages of apprentices are low during their training period as they partly pay for their training through reduced remuneration (see Dustmann and Schoenberg 2012). However, after completing the training, their wages increase sharply and continue to grow slowly over the next two decades. In contrast, those who enter the labour market directly after secondary school experience rapid wage growth in the first five years, but their real wage growth slows down significantly after that. Twenty years after graduating from secondary school, workers who underwent apprenticeship training have wages that are about 15 per cent higher than those of the untrained.

Figure 1. Log wage by training status

Notes: IAB Social Security data, 1975-2004. See Sections 2.3 and A for details. Potential experience is counted down from entry into the labour market for untrained workers and from the start of training for trained workers.

Although Figure 1 provides some insights into the benefits of apprenticeship training, it does not reveal the complete picture. Our study uses a causal model to evaluate the channels that benefit workers who choose apprenticeship training while addressing potential self-selection biases. The analysis shows that apprenticeship training offers access to better jobs with more growth potential, which leads to sustained wage growth later in the career. It also allows for a faster accumulation of work experience and reduces the likelihood of unemployment while easing the transition back into work. In contrast, workers who do not undergo apprenticeship training have a higher risk of unemployment and a lower probability of returning to work from unemployment.

Overall, apprenticeship training provides significant career advantages, including more continued wage growth, access to better jobs, and reduced layoff risk. However, vocational training programs may only be suitable for some workers since they choose these programmes according to their innate abilities. Therefore, more than an assessment of vocational training programmes based on immediate returns alone is needed, and it is crucial to consider the longer-term effects of such programmes on career outcomes.

We also explore the societal advantages of adopting apprenticeship programmes, which can be a pricey investment for companies and taxpayers. By calculating the expenses of training and comparing them to the benefits of enhancing workers’ career opportunities and lowering unemployment rates, we demonstrate that the overall societal rate of return is approximately 10%. Therefore, apprenticeship training yields substantial benefits to both individuals and society (see Doepke et al. 2017 for assessment from a historical perspective).

Why do wages grow?

According to our examination of workers’ wages throughout their lifetime, skill development is the primary catalyst for early wage growth. Specifically, routine-manual skills substantially impact productivity and earnings in the first few years of a worker’s career, while cognitive-abstract skills, which can be acquired more quickly through apprenticeship training, lead to sustained wage growth throughout their careers career. Another crucial factor for wage growth is job mobility, accounting for approximately one-third of wage increases within the initial five years of employment. Switching between different jobs allows young workers to find positions where they can be most productive, resulting in a significant boost in earnings concentrated during the early stages of their careers.

Do workers change jobs only for monetary reasons?

Workers primarily change jobs to maximise their income by choosing the job with the highest wages and best career prospects. However, non-monetary factors such as working conditions, interaction with colleagues, and ease of commuting to the workplace are also important reasons for changing jobs. In fact, during the early years of a worker’s career, non-monetary job amenities account for about 25% of job-to-job transitions. As a result, non-monetary job amenities are a crucial factor in workers’ decision-making.

What determines the type of jobs workers choose and what are “lock-ins”?

Workers’s decision to choose jobs that predominantly require routine-manual or cognitive-abstract skills depends on both unobserved sector-specific “talent” and observed past educational choices. Additionally, it also relies on the accumulation of different sector-specific skills obtained through working in various occupations. This phenomenon can lead to “lock-in” effects, where workers initially assigned to a sector for which they have less talent accumulate experience specific to that sector, disincentivising them from moving to jobs in a sector where they have more talent. For example, if a worker’s innate ability is better suited for an office job, but they start their career as a car mechanic due to limited options, changing sectors after a few years can result in substantial costs due to the loss of accumulated sector-specific skills. Recessions can exacerbate occupational lock-in effects by limiting sector choices.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on “Sources of wage growth.” Journal of Political Economy (2023.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Shoeib Abolhassani on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.