Organisations increasingly rely on external participants and draw on online platforms to secure talent. However, this approach has been insufficiently conceptualised and needs a lot more detail to be represented as strategic. Leslie Willcocks writes that how the flexible labour organisation is managed will affect labour attraction and retention, the skills base, technology use and productivity.

Work (and its posited futures) has been through a fraught period. From mid-2020 we witnessed the pandemic-induced shifts to remote and home working, now more than twice as prevalent as before COVID-19. Some 76 per cent of companies have adopted hybrid working, though many are still not sure of the optimal home-office work balance to adopt.

From mid-2022 there followed the ‘Great Resignation’ – ostensibly, many people in the developed economies giving up work and not taking up new employment. By late 2022 the topic of overreach set in, with major companies in hi-tech, banking, management consultancy – and Amazon – sacking thousands of workers because they had overestimated economic pickup and demand trends.

On a longer timescale going back to 2014, there were fears of massive job loss from accelerating automation and the digitalisation of work. But recent, serious reports downplay this, predicting that between 2019 and 2030 the net global job loss is likely to be around one per cent. Then generative AI and ChatGPT set off new alarm bells. According to a BBC report, Goldman Sachs claimed that by March 2023 “AI could replace equivalent of 300 million jobs”. No timeline given, and it’s a global extrapolation from US and European data. But best anyway to look beyond the headlines where the report says: “The good news is that worker displacement from automation has historically been offset by creation of new jobs, and the emergence of new occupations following technological innovations accounts for the vast majority of long-run employment growth”. The report itself points to labour cost savings, new job creation, and higher productivity for non-displaced workers. These factors would likely increase productivity and economic growth ‘substantially’ – again no timeline given.

Recent research by myself and others suggests that dramatic skills changes and shortages are the real serious challenge to productivity, technology adoption and economic growth through to 2030. But how are employers responding? According to an MIT/Deloitte 2021 report, a pre-COVID and continuing trend is ‘workforce eco-systems’ – trying to find multiple sources of internal and external skill using various contractual arrangements, global markets, and reward systems, and by forming communities of connected and interdependent workforces and organisations. Organisations are placing significant value on gaining ideas and skills from contributors who do not work for them. And they intend to rely increasingly on external participants and draw on on-line platforms to secure talent.

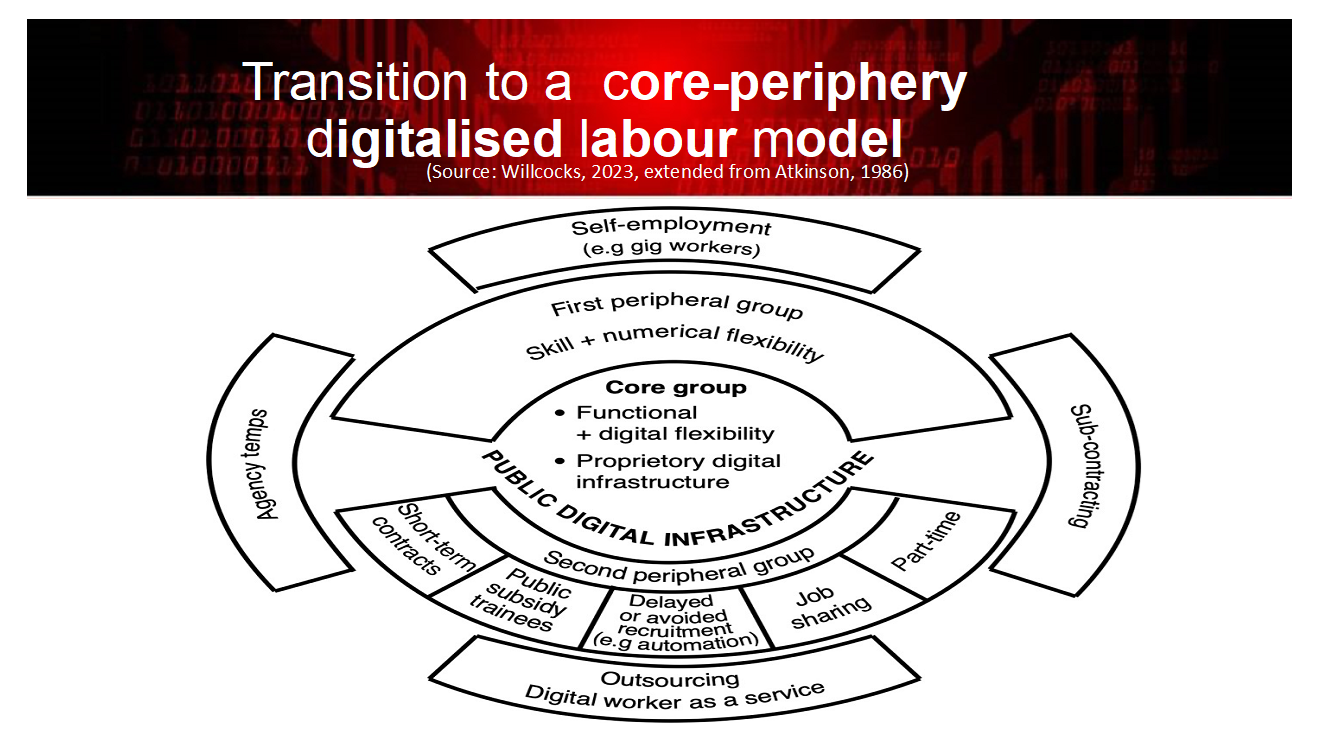

However, this approach has been insufficiently conceptualised, and needs a lot more detail to be represented as strategic. Recent research at LSE together with Knowledge Capital Partners shows most organisations adopting key elements of a ‘core-peripheries’ model for organising labour, though they tend to do this on an ad hoc basis, in response to short-term factors. These include labour shortages, the need to keep costs low, and attempts to harness digital technologies productively, for example to support home working during the recent pandemic. Figure 1 shows this major trend towards what I will call the digitalised flexible labour organisation.

Figure 1. The digitalised flexible labour organisation

The overall objective is to achieve responsiveness and agility through creating three types of flexibility – functional, numerical and financial. This flexible model was first proposed as far back as 1984 by John Atkinson. The core workers represent the key skills and are viewed as long stay employees with favourable terms and conditions in exchange for which they will be functionally flexible, supported by training and development, and new technologies. The first peripheral group may also work full time or part time but do the less key work and tend to have fewer good terms and conditions.

Then there are multiple, other, more transactional relationships as the organisation draws on agency workers, sub-contractors, outsourcing firms, self-employed workers, including the open talent economy available globally for mixed skills depending on requirement. This gives employers some functional, but mainly numerical and financial, flexibility. In recent years digital technologies have been providing three more types of flexibility – locational (think remote working) temporal (think 24×7), and labour replacement/enhancement flexibility (through automation and online ‘robo-sourcing’.

So far so impressive. However, the MIT/Deloitte survey also reports that over three quarters of respondents are not sufficiently prepared to manage a workforce consisting mainly of external participants. Our own work is more granular and is discovering emerging, unanticipated challenges:

- If the model is assembled through a series of short-term responses, you find that sooner rather than later the organisation runs out of road. There needs to be a strategic intent to look after the sustainability of the business over a moving five-year time horizon.

- Core workers are key as they carry the culture, core skills and provide vital agility in today’s volatile, uncertain environment. However, there are signs that the model in practice is eroding organisational cultures. Many employees do not behave as core workers – too often they seek to leave the organisation in search of career progression. Employers do not treat their employees as core either. Thus the renewed emphasis during 2023 on employee experience to right this trend.

- The peripheral arrangements tend to be transactional and contractual in character – this does not breed key cultural values amongst these workers. Furthermore, as we found when looking at outsourcing, the management and transaction costs of operating contractually can be surprisingly high.

- The model needs to be operated as a strategic approach to labour utilisation, with a core group responsible for ensuring that both core and peripheral workers are properly treated and trained to do the tasks allocated to them. I am not sure that HR organisations are up to this task in most organisations. If not, then it is definitely an area to be worked on.

- Does this mode of operating respond sufficiently to skills shortages? Clearly, it makes labour utilisation more flexible, and can draw on a wider, even global talent base. It can also harness the expanding possibilities of automating work, human-machine work design and cloud-sourcing a digital workforce. In the best versions, core workers will receive substantial training and development. But old habits of cutting training budgets first die hard, especially when the organisation is struggling, or at least acting early to lower costs to protect the balance sheet and spending more on resilience, for example in cybersecurity and supply chains. Historically, periphery workers have been left to fend much more for themselves, while ‘the war for talent’ has been less about training and development, and much more about competitive hoovering up skills at the market price. That tends to create winners and losers, not skills surpluses.

There are some constructive ways forward. My own view is that retaining and building the core workforce must be the priority target. There has to be strategic clarity around that objective. One part is defining a core worker in the light of strategy and changing contexts. This is by no means easy to do if organisations do not have great clarity about their purpose, operating model and values. Many do not.

Internal labour markets and high velocity horizontal fast tracks can do much to encourage and develop core workforce members. This was a big practice amongst major Japanese companies in the 1980s, when they were at the height of their success.

Abundant evidence shows that organising into small cross-functional teams given discretion on how to achieve measurable goals and performance is a productive use of core labour, and indeed some other peripheral workforce members.

Peripheral workers need to be drawn closer into the main organisation and its culture. For example, adopting across the organisation principles of economic integrity, societal equity and environmental integrity and fair reward, might well help here. One of the important findings on remote workers is that they experience work-home interference, poor communication, procrastination and loneliness. Closer monitoring and intensifying the workload tends to undermine rather than make such workers more productive. Meanwhile, much more social support, including some 1-2 days in the work office seems to have the most beneficial effects.

These are just some observations. Dramatic skill shifts require major actions and interventions by governments, educational systems, businesses and workers themselves, sustained over time. But how the flexible labour organisation is managed will have a lot of consequences for labour attraction, retention, building the skills base, the utilisation of technology, and productivity achieved.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Memento Media on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.