A sufficient supply of euro-denominated safe bonds, those rated triple A, is critical for the EU’s banking and capital markets union and to foster the euro’s international role. It would also help ease the world’s safe asset scarcity. The EU debate has so far focused on the possible creation of common or supranational safe assets. This has underplayed the potential contribution of sovereign assets. Francesco Papadia and Heliodoro Temprano-Arroyo suggest a strategy to correct this bias.

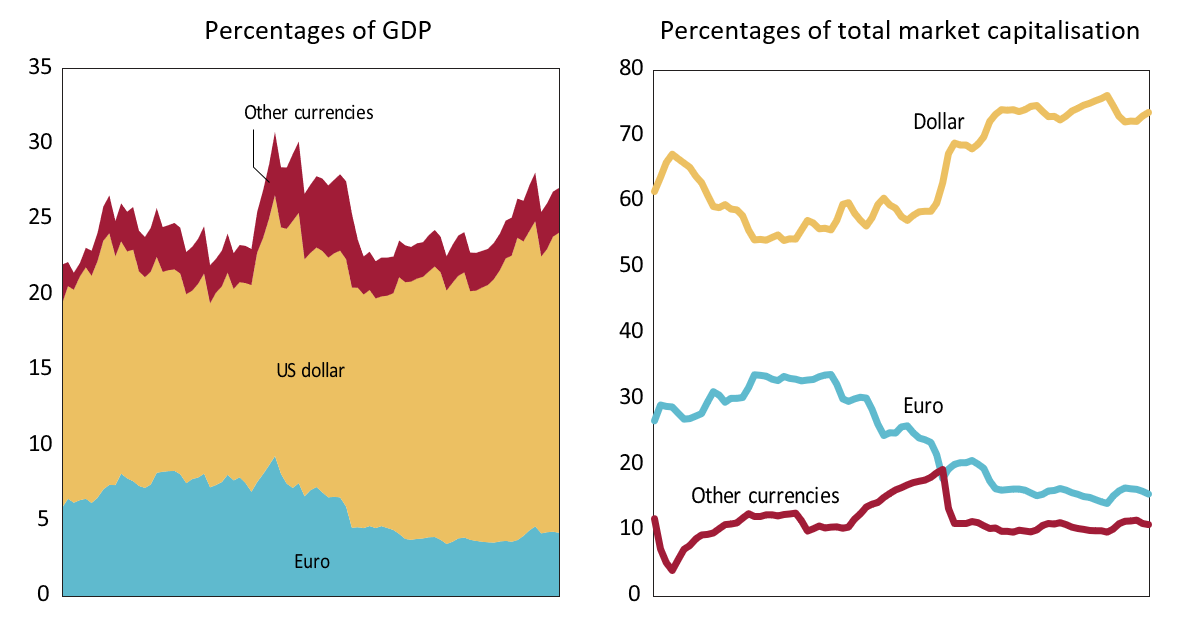

After its inception, the euro gained international traction but still accounts for a much lower share of the global supply of triple-A assets than the US dollar. The global financial crisis and the subsequent euro area sovereign debt crisis resulted in a sharp decline in the euro’s share of safe assets, as illustrated by Figure 1. This reflected the downgrade of sovereign credit ratings, which reduced the number of triple A-rated euro area treasuries from eight to only three (Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands). Because the crisis also prompted a flight to quality, this markedly worsened the scarcity of safe assets in euro and exacerbated the global shortage of safe assets highlighted by the economic literature (Caballero, Farhi and Gourinchas, 2017).

Figure 1. Market capitalisation of AAA assets

Source: Papadia and Temprano-Arroyo (2022). Note: Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate – AAA Index, which includes triple A fixed-income securities issued by treasuries, other government-related institutions and corporations. Quarterly data.

Common and supranational safe assets

With the euro area’s banking system on the verge of collapse, the euro area crisis triggered a lively debate on the possible creation of a common safe asset that would mitigate the risk of vicious circles between banks and sovereigns (the so-called bank-sovereign doom loop) by reducing the home bias in banks’ portfolios of government securities. Over time, the debate moved from proposals involving a degree of debt mutualisation to others not requiring the provision of explicit debt guarantees (ECB, 2020; Leandro and Zettelmeyer, 2019). In recent years, it has focused on the possible creation of a synthetic safe asset, as exemplified by the European Safe Bond (ESBies) proposal of Brunnermeier et al. (2016) and the related sovereign bond-backed securities (SBBS) proposal presented by the European Commission in 2018. So far, however, there has been limited political appetite for these ideas, partly reflecting misgivings by fiscally conservative euro area countries. Moreover, these synthetic safe asset proposals are not without shortcomings, as stressed by De Grauwe and Weil (2018) and Claeys (2018).

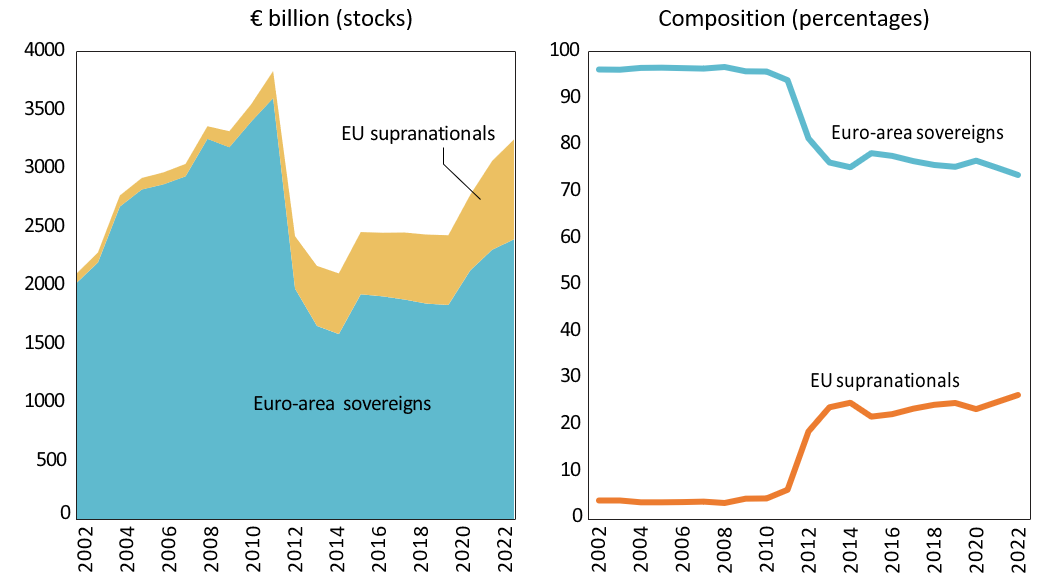

Following the creation of the Next Generation EU (NGEU) and the Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE) instruments in response to the COVID-19 crisis, interest has shifted towards the contribution that EU supranational facilities could make to the issuance of euro-denominated safe assets. Indeed, the new facilities are providing a historical boost to the supply of EU supranational bonds. Issuance under both facilities could reach up to €906.9 bn by 2026 and is contributing to a radical modernisation of the Commission’s borrowing strategy and infrastructure (Temprano-Arroyo, 2022). The large issuance of securities under the new facilities is intensifying a trend, already visible since the euro area crisis, towards an increase in the share of supranational assets in the stock of euro-based public safe assets (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Sovereign versus supranational safe assets in euro, 2002-2022

Source: Papadia and Temprano-Arroyo (2022)

The role of sovereign safe assets

The focus on common and supranational safe assets has tended to play down the potential role of sovereign safe assets. Indeed, Figure 2 shows that, despite the decline in the share of sovereign assets, they still represent the main source of euro-denominated safe assets. Expanding their supply, notably through the gradual implementation of fiscal and growth-oriented structural policies in euro-area countries, leading to sovereign rating upgrades, provides a promising, and perhaps more feasible, option to boost the supply of safe assets in euro. In a recent paper (Papadia and Temprano-Arroyo, 2022), we show that achieving an upgrade to triple A of those euro-area countries that are currently rated double A could produce substantially more safe assets than most common safe asset proposals, including those based on the development of ‘synthetic’ safe assets.

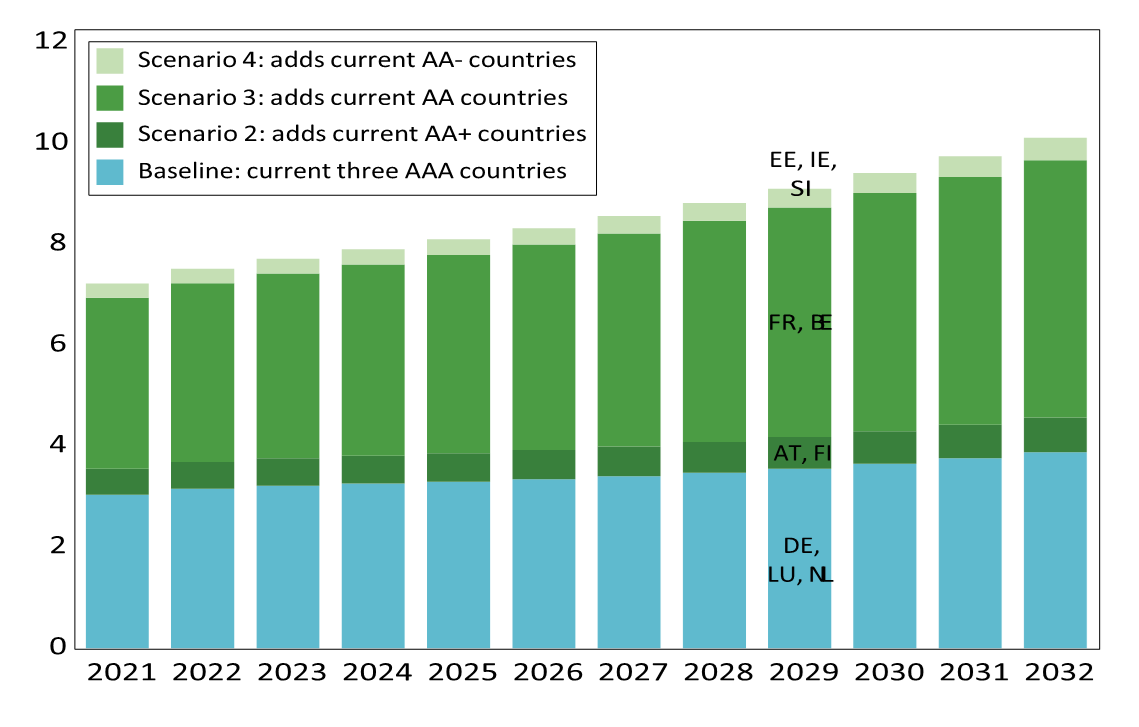

Figure 3 illustrates this by displaying several credit-rating scenarios for euro area countries, using for the underlying debt figures the Commission’s medium-term debt projections. For example, under scenario 3, in which four double AA countries are upgraded to the triple A category, safe assets would increase by €5.8 tn by 2032 compared to the baseline. This is six times the maximum issuance allowed under the NGEU and SURE facilities combined and is above the safe asset creation estimated by most proposals for a European common safe asset (Temprano-Arroyo, 2022).

Figure 3. Supply of euro-area sovereign safe assets under different rating scenarios (€ trillion; end-of-year)

Source: Papadia and Temprano-Arroyo (2022)

A multi-pronged safe asset strategy

We therefore believe that the EU should pursue a multi-pronged safe asset strategy. First and foremost, sound fiscal policies and ambitious growth-stimulating reforms – which are in any case desirable – should be implemented by euro-area sovereigns to improve their credit ratings. Given the challenging economic and debt situation currently experienced by euro-area countries, these policies might not be politically feasible in the short-term. Nevertheless, they should be a key component of an EU medium-term strategy to foster the supply of safe assets, and they are actually already part of the guidance provided under the European Semester.

Second, national efforts should be complemented by an adequate supply of supranational assets from existing EU facilities, or from new ones to be created, possibly in the context of the financial response to the war in Ukraine and its ramifications for the EU. Indeed, Ukraine faces huge macroeconomic stabilisation and reconstruction needs. In response, the EU has adopted unprecedented packages of Macro-Financial Assistance loans – of more than €7 bn in 2022 and up to €18 bn in 2023 – to help cover Ukraine’s short-term funding needs. The European Commission (2022) has also recommended the creation of a new facility to address Ukraine’s longer-term reconstruction needs. While the details of this facility must still be spelled out, it could potentially lead to the issuance of a new type of supranational bonds in euro. The war in Ukraine might also lead the EU to adopt other multi-billion initiatives to address, for example, the economic fallout of the energy crisis or to ramp up EU defence expenditure, even if such initiatives are not currently on the table.

All this means that the issuance of EU supranational bonds will remain a substantial source of safe assets in euros for years to come. However, there are limits to the capacity to expand the supply of supranational safe assets. All EU supranational facilities are, in one way or another, ultimately guaranteed by EU countries. If not backed up by prudent fiscal policies at the national level, a rapid expansion of supranational borrowing could result in the downgrade of the entities managing those facilities. It is therefore of paramount importance to ensure the creditworthiness and high ratings of the sovereign guarantors behind these facilities.

Finally, should the political consensus be found one day to create a common safe asset, such an asset could be incorporated into the euro area’s existing safe asset system, reinforcing its positive effects.

Although common and supranational safe assets have certain advantages over national safe assets, reflecting their built-in risk diversification properties, the latter already offer many of the advantages of the former. Moreover, the upgrade of sovereign ratings would have positive spillovers on the other two components of the proposed safe asset strategy. In particular, it would improve the quality and attractiveness for investors of EU supranational assets through the system of explicit and implicit guarantees from EU countries.

Additionally, a more general improvement of euro area ratings, including in countries that will remain below the triple A notch, could strengthen the safe asset-creation properties of some of the common safe asset proposals. For example, it would allow a larger senior tranche in the case of the SBBS. Improved ratings among lower rated countries would also reduce the risk that a regulatory reform aimed at decreasing the home bias in banks’ portfolios will have the unintended consequence of increasing international contagion risk, thus replacing the loop doom problem with another type of financial instability risk (the Alogoskoufis and Langfield, 2018 critique).

In sum, expanding the supply of sovereign safe assets through the upgrade of credit ratings should be a key ingredient of the EU’s safe asset strategy. It would bring both direct and indirect benefits. While experts and policy makers have focused so far on the potential contribution of common and supranational safe assets, the role of sovereign assets has received too little attention. We believe it is time to redirect the debate towards the large contribution that sovereign rating upgrades could make to the supply of euro-denominated safe assets, not least given the additional benefits the required policies would bring.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post represents the views of its authors, not the position of their institutions, LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Guillaume Périgois on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.