If raising the Bank of England rate were a strong psychological signal to consumers that inflation would come down quickly, the whole process could be speeded up. But the Bank’s credibility has taken a hit, so the psychological mechanism is weaker as a result. Paul Whiteley writes about the dilemmas in the fight against inflation.

The Bank of England has raised interest rates thirteen times over the last couple of years to try to curb inflation and finally it is falling to 7.9 per cent in June compared with 8.7 per cent in May. The mechanism at work is to make credit more expensive by raising its price which is a rate of interest known as bank rate. This underpins the cost of all types of credit, including loans to businesses and individuals as well as rates paid on credit cards and mortgages.

The idea is that raising the costs of credit reduces economic activity because individuals will curtail their borrowing, increase their savings and so spend less. This in turn will bring down inflation. A side effect of this is to slow the economy and raise unemployment.

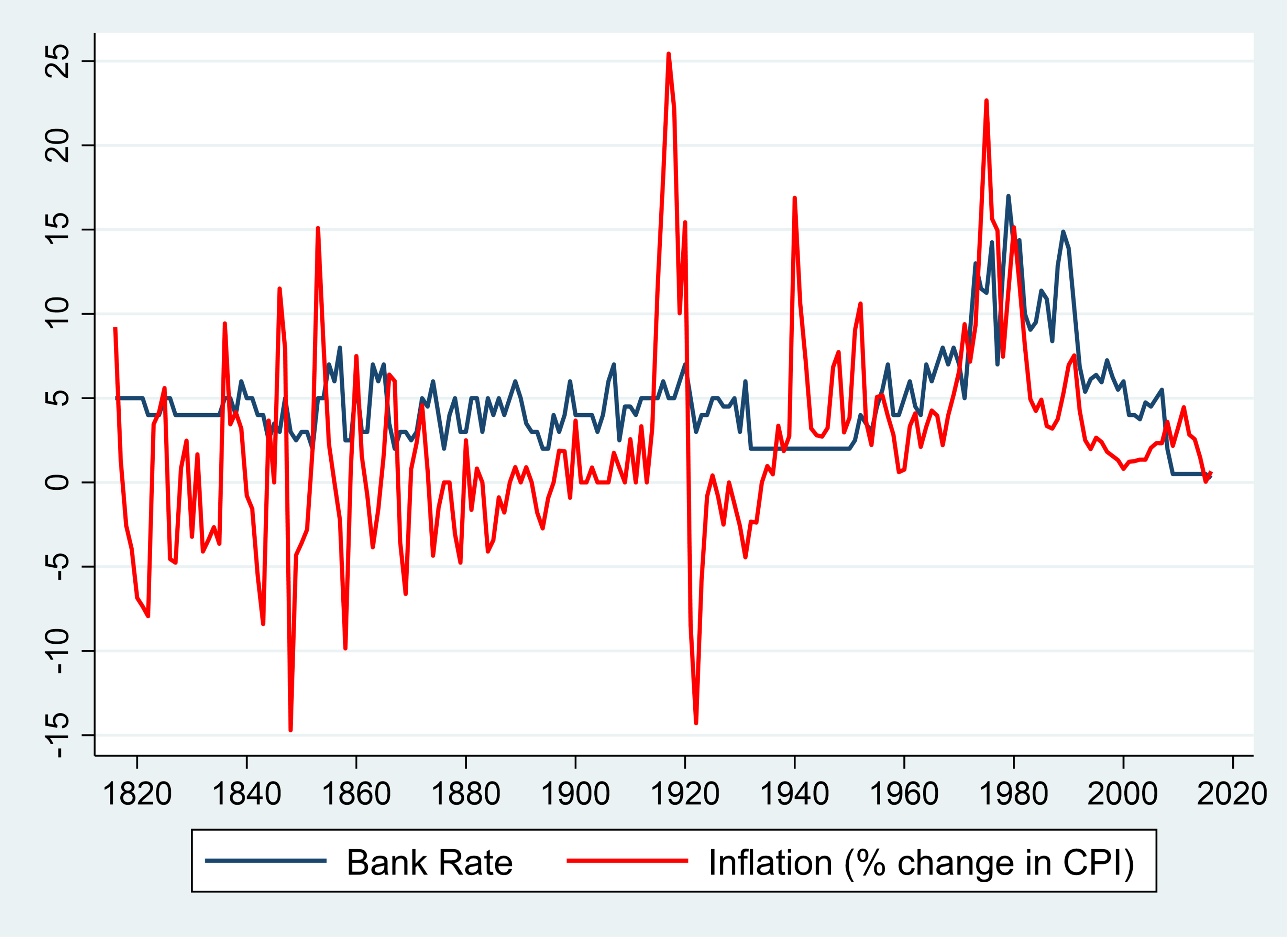

However, how does this mechanism actually work? The chart identifies a puzzle in understanding the process. It looks at the relationship between bank rate and inflation over a long period of 200 years. The puzzle is that they move together so that when bank rate is high so is inflation, and vice versa. If increases in bank rate reduce inflation, then they should move in the opposite direction to each other, not in the same direction.

Figure 1. The relationship between bank rate and inflation 1816 to 2016 in the UK

Source: Bank of England Statistic Research Datasets

It is not easy to see in the chart, but the correlation between inflation and bank rate over this period is 0.37. This is not a strong correlation, but it is positive and statistically significant, meaning that it cannot be attributed to chance. To be fair, inflation does not necessarily respond to changes in bank rate in the year that these occur. Economists like the late Milton Friedman argued that there are significant lags in the adjustment of inflation to changes in interest rates. But if we examine the correlation between bank rate in the previous year and inflation in the current year, again it is positive, not negative.

How, then, does raising interest rates help to bring down prices? The traditional answer to this question is the ‘Phillips curve’. This measures the relationship between inflation and unemployment, and over our 200-year period they have been negatively related, with a correlation of -0.38. When unemployment rises, inflation falls.

But there is a problem in this mechanism, namely the long lag between increases in bank rate and subsequent increases in unemployment. If inflation is to be reduced within a reasonable period of time, then bank rate should raise unemployment fairly rapidly. However, the correlation between bank rate and unemployment in the same year is very weak (r=0.08). It only grows stronger as lags in the relationship grow longer.

It actually takes seven years for this correlation to reach a maximum value of 0.42 at which point bank rate has a big impact on unemployment before it starts to decline. The implication is that inflation is very ‘sticky’ and we will need a significant recession to bring it down. This actually happened in the period 1980 to 1984 when Geoffrey Howe, the chancellor of the exchequer, introduced the Medium-Term Financial Strategy with the aim of curbing inflation. Between 1980 and 1982, unemployment more than doubled from 5 per cent to almost 12 per cent.

The great economist John Maynard Keynes wrote: “the rate of interest is a highly psychological phenomenon”. In other words, rapidly rising prices make people pessimistic, reducing their spending and in addition discouraging business investment. Human psychology is an alternative and much quicker mechanism than the traditional Phillips curve.

We can see the effects of this by looking at consumer confidence, a measure of people’s optimism and pessimism about the state of the economy over time. The consumer confidence index fluctuates around 100 with scores less than that denoting pessimism and scores above that optimism.

The data on consumer confidence goes back to 1974, so we cannot look at this over the whole period. But if we examine the period from then until 2016 the correlation between consumer confidence and inflation is strongly negative (r= -0.47). This simply confirms the point that rapidly rising inflation makes people less likely to spend money. The index is also negatively related to unemployment although this relationship is much weaker (r= -0.15).

Taken together, these data show that bank rate is a rather poor instrument for controlling inflation, since it works very slowly via unemployment. It can work much faster via human psychology, but the problem with this is that widespread pessimism among consumers is likely to make recovery much slower once inflation has come down.

If raising bank rate was a strong psychological signal to consumers that inflation would come down quickly, then the whole process could be speeded up. Unfortunately, the credibility of the Bank of England has been called into question recently and so the psychological mechanism for reducing inflation is probably weaker as a result.

Other actors such as the government can influence inflationary expectations as well, but this is unlikely to occur in the case of the present government. This is because markets and consumers were severely spooked by Liz Truss’s short tenure in Downing Street, calling into question the competence and credibility of the government.

Raising bank rate gradually to try to nudge down inflation is probably a good idea, but it requires time to work. Raising rates rapidly is folly since it is likely to increase unemployment after a long lag and, in the immediate future, make people so pessimistic about the economy that it has a hard time recovering after inflation has been conquered.

- This blog post represents the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image provided by Shutterstock

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.