Communities with higher levels of trust are better able to cope with crises. However, trust goes down in times of food scarcity when the need for cooperation is at its highest. The economic implications are deep. Gustav Agneman, Paolo Falco, Exaud Joel and Onesmo Selejio studied a group of farmers in Tanzania and tried to identify how food scarcity causally affects trusting behaviour, thereby reducing the resilience of the community.

The interaction of conflict, climate shocks, and the COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increased incidence of hunger worldwide. 2023 has been called “a year of unprecedented hunger” by the World Food Programme (WFP) and, according to the UN Secretary General we may face “the spectre of a global food shortage“. The WFP reports that, since the COVID-19 pandemic started, the number of people experiencing or at risk of experiencing acute food insecurity has more than doubled.

“You cannot trust anyone with food when it is the time of hunger”, according to a farmer that the anthropologist Kristin D Phillips encountered during her field work in Singida, central Tanzania. The region typically experiences seasonal spells of food shortages in the months before the yearly harvest. The lean season after the drought in 2005-2006, when Phillips conducted her field trip, was especially bad. It is easy to see why the farmer was less trusting when food was scarce.

Trusting entails an element of risk, as the counterpart may renege on his/her promises. Scarcity amplifies the consequences of broken promises. In severe cases of food scarcity, the historian Cormac Ó Gráda notes that “Primeval impulses, such as […], the need to socialise and cooperate, the desire to help others, […], give way to drastic efforts to preserve one’s own being”. For subsistence-based farmers like those in the city of Singida, Tanzania, who rely on “relationships of reciprocity and exchange”, a breakdown of cooperation can have long-lasting effects.

In our study, we set out to identify how food scarcity causally affects trusting behaviour. We revisited Singida and collected data before and after the yearly harvest. We elicited a measure of trust through an economic game called the Trust Game. In it, one participant (Player A) decides how much to invest in a joint venture with another participant (Player B). Player B decides how to divide the payoffs (real money) between themselves and Player A after the venture has resulted in positive returns. Player A’s investment provides an incentivised measure of trust since it is contingent upon trusting the (anonymous) other player to send back a positive return.

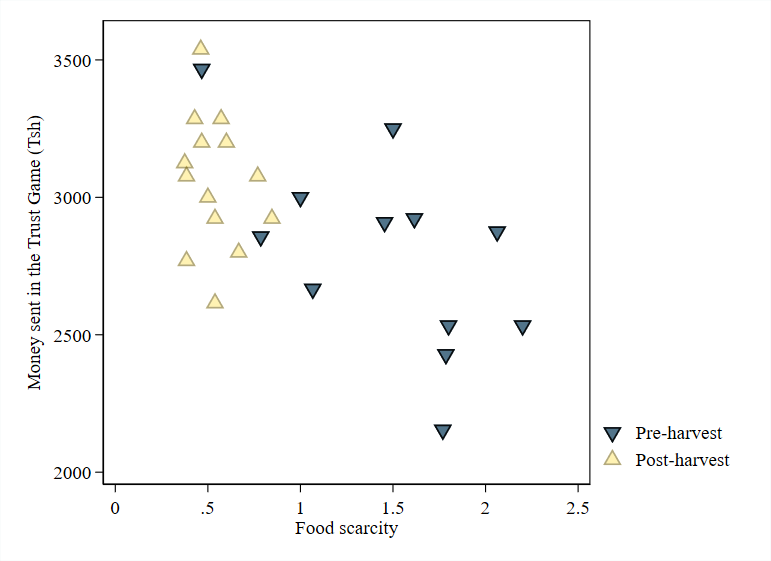

Figure 1. Food scarcity before and after the harvest

Note: Food scarcity is measured as the response to the following question: “Over the past month, how often, if ever, have you or anyone in your family gone without enough food to eat?”

By comparing trusting behaviour among farmers before the harvest (relative scarcity) with trusting behaviour after the harvest (relative abundance) we find evidence of a significant drop in trust during the lean season. Prior to the harvest, players invest 10 per cent less than what they invest afterwards. The negative effect of food scarcity on trusting behaviour is evident both in comparing the behaviour of different farmers (all farmers) and in comparing pre- and post-harvest behaviours of participants who completed the game twice. Since investments yield positive social as well as private returns (on average, Player Bs send back more than Player As’ initial investments), the behavioural consequences of scarcity further compound the negative welfare implications.

Figure 2. Trust, food scarcity, and the post-harvest treatment

Note: The correlation between village level food scarcity and trusting behaviour, separately for pre-harvest (dark markers) and post-harvest (post-harvest).

We undertake several complementary analyses to corroborate the conclusion that food scarcity breaks down trust. First, we control for a range of other time-varying factors, such as festivities and financial resources. Second, we use the exogenous shock in food supply to instrument food scarcity and demonstrate a strong statistical link with trusting behaviour. Third, we use satellite imagery of land usage to show that trusting behaviour varies more in areas where populations depend more heavily on crop agriculture for their food supply. Finally, we use experimental variation in the instructions to demonstrate how scarcity hurts especially inter-group (as compared with intra-group) cooperation. This finding supports the notion that networks of cooperation may shrink in times of scarcity, a tendency that could exacerbate the negative effects of food scarcity, since diversification requires extensive cooperative networks.

The results should not be generalised without caution. According to other studies on crises and behaviour, notably Cassar et al. (2017), some crises may in fact promote human cooperation. They found that cooperative behaviour increased in communities that were heavily affected by the 2004 Tsunami. A potential explanation for the divergent findings is the nature and scale of the adverse shocks. Whereas natural disasters are sudden and unexpected, and present residents with collective challenges, seasonal scarcity is progressive and anticipated, and may pit individuals’ interests against one another. Taken together, the evidence suggests that adverse events do not influence cooperative behaviour in a deterministic fashion. Rather, the behavioural consequences depend on the type of shock and how society responds.

Our study shows that trust goes down when the need for cooperation is at its highest, which has deep economic implications. Communities with higher levels of trust are better able to cope with crises. The detrimental consequences of food shortages on trusting behaviour suggest that a temporary hunger spell could have long-term effects on economic performance by upsetting cooperative networks. Consequently, hunger relief may not only serve to alleviate suffering today but also promote a more prosperous society tomorrow.

- This blog post is based on The Material basis of Cooperation: How Scarcity Reduces Trusting Behaviour, in The Economic Journal, Volume 133, Issue 652, May 2023.

- The post represents the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image provided by Shutterstock

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.