The UK investment ecosystem needs rewiring across the board to increase firms’ desire to invest in productive and sustainable assets, and to enhance their ability to do so. Paul Brandily, Mimosa Distefano, Krishan Shah, Gregory Thwaites and Anna Valero set out why this matters and what to do about it.

The UK is a low investment nation. This matters. It means that workers have less kit to work with, worse infrastructure to rely on and fewer ideas to implement – and it leaves fewer UK firms able to compete in the global economy. That translates into lower productivity, holding back wage growth and improvements in all of our living standards. Living off the past, not investing in the future, has consequences.

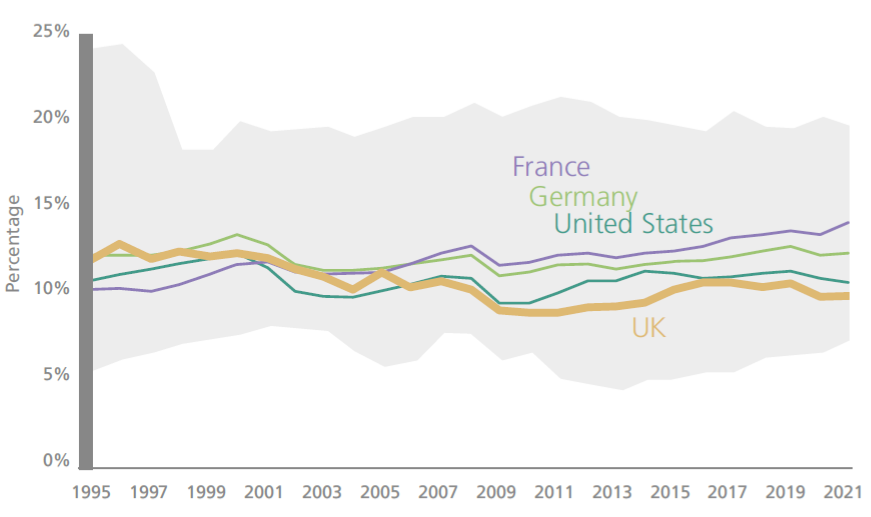

Businesses are responsible for around two-thirds of national investment. Business investment fell in the 2000s as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), it fell further during the global financial crisis of 2007-09 and it has stagnated since 2016 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gross fixed capital formation of the corporate sector as a proportion of value added, by country: 1995-2020

Notes: Range includes ‘high income’ OECD countries, specifically, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, United States. Source: Analysis of OECD, gross fixed capital formation database. Used in the Economy 2030 report, Beyond Boosterism.

If UK business investment had matched the average of France, Germany and the United States since 2008 – something that would have required just over 2 per cent of GDP additional investment each year – our GDP would be nearly 4 per cent higher today, enough to raise average wages by around £1,250 a year.

A growth boom is badly needed by UK workers, whose real wages have only just surpassed pre-financial-crisis levels, and the evidence suggests that growth booms are nine times more likely if investment is also booming. And wider objectives, from levelling up to net zero, also require large scale private investment in the years ahead if they are to be achieved. Reviving the UK’s economic performance means the national future must involve higher investment levels than in the recent past.

Raising firms’ willingness to invest is central

A period of political and economic stability will help. But it will not be sufficient. As well as stability, a clear economic strategy for how the UK will succeed in the years ahead (the focus of the Economy 2030 Inquiry) will include strategies for specific industries and objectives – in particular, net zero.

A precursor to firms investing is them wanting to do so. Many people look at low investment levels and say this must reflect firms not being able to make sufficient return on investments in the UK. The result is often a policy debate focused on corporation tax.

There is certainly scope for government to encourage investment with the right corporation tax regime. The government should immediately make permanent the (currently temporary) full expensing of business plant and machinery.

Broadening which investments can be fully expensed to all business capital is also desirable, if costly, in the short run. Any lasting costs should be defrayed by tightening the limits on the tax deductibility of interest, reducing the tax system’s bias towards debt financing. More importantly, governments should commit to keeping the corporation tax regime – both its rate and allowances – stable over time.

Tax incentives for research and development (R&D) are also important for ensuring that smaller, more innovative and typically more financially constrained firms are supported. Enhanced incentives for net zero (or other strategic) investments should also be explored.

Although we should get our tax regime right, it is not the main driver of low investment in the UK. Nor are rates of return: our analysis shows that low investment goes alongside a relatively high average profit rate on existing capital in the UK – past investors have done well.

This implies that the management of UK firms are not investing despite there being returns to be had, and this fits with other evidence that UK firms are substantially less well-managed than US firms, leading to lower productivity, profits, R&D expenditure and patenting. Poorly managed firms also make less accurate forecasts, which leads to lower investment.

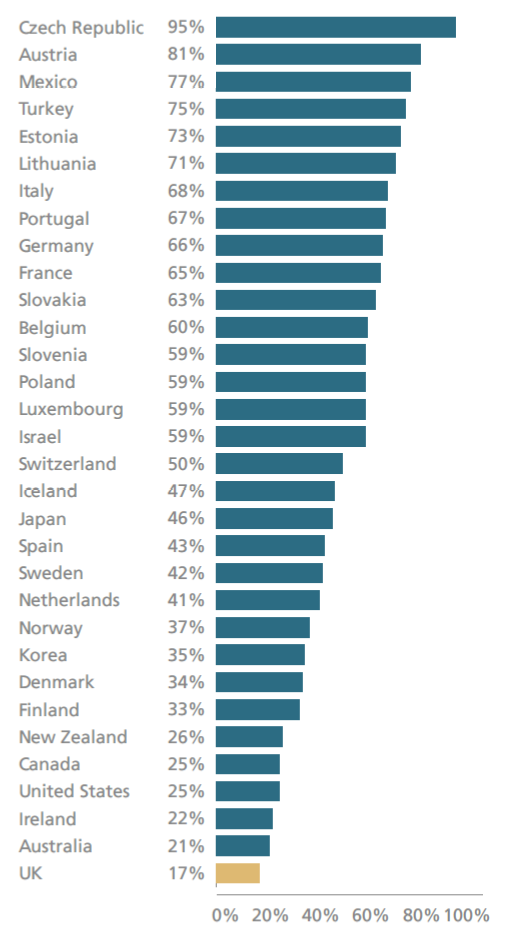

The UK also stands out for the extent to which those managers are under uniquely little pressure from above (owners) or below (workers) to focus on long-term growth. This reflects the fact that the ownership of UK-listed firms has become more remote – with foreign ownership of UK public firms rising from just over 10 per cent in 1990 to over 55 per cent in 2020 – and extremely dispersed (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Proportion of listed companies that have a controlling shareholder, by country: 2012

Notes: Controlled firms identified using a Shapley-Shubik algorithm to identify owners that have enough votes to change vote decision. The algorithm has been adjusted to allow for owners in the same corporation to act in unison. A firm is classified as controlled if its Shapley-Shubik power index is 75% or greater. Source: Gur Aminadav and Elias Papaioannou (2020) ‘Corporate Control Around the World’, Journal of Finance 75(3):1191-1246. Used in the Economy 2030 report Beyond Boosterism.

Meanwhile, workers in UK firms lack the sort of voice or formal role in corporate governance seen elsewhere in Europe. The challenge is to bring the voice of owners and workers back into the picture, so managers without a long-term plan feel the pressure both from above and below to do something differently.

Risk of concentrated ownership

There is an active debate in the UK about how best to encourage pension funds to return to UK-listed shares, largely motivated by the idea that the provision of more capital will drive higher investment by these firms. In aggregate, though, there is little evidence that the lack of finance is a major barrier to investment among established firms. Instead, we should consider pension reform as a route to raising investment levels by rebuilding concentrated firm ownership.

Structural and regulatory forces in the pensions system have weakened the extent to which pension funds have acted as engaged owners of UK firms. Private defined benefit (DB) pension schemes, formerly the anchor investors in the UK stock market, have largely vacated it. Defined contribution (DC) schemes, with 20 times as many active members as DB schemes, are fragmented and almost exclusively invest passively through pooled investments. Our DC and DB pension funds in aggregate now allocate only 2 per cent of their assets to directly held UK equities.

The result is UK firms having the lowest share in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) of “blockholder” shareholders who are big enough to affect firm decisions on their own. To underpin a return to significant block ownership, policymakers will need to consider each strand of the pension landscape – legacy DB, DC and local government pension schemes (LGPS) – separately. But the common objective is a pension funds ecosystem that not only holds more UK equities but does so via far larger funds able to provide more concentrated – and therefore engaged – ownership as well as investing more in unlisted high growth firms and infrastructure projects. DB schemes hold assets worth £1.7tn, around 70 per cent of all pension assets, and have driven most of the move out of equities and into bonds over the last 20 years. Many DB schemes are on an exit ramp out of existence, so the real question is not how they are regulated, but where does that exit ramp take them and their assets. It is likely that schemes will be bought out by insurance companies that would provide scale but, due to their regulation, will largely hold the transferred assets in very low-risk assets.

But the UK Pension Protection Fund (PPF) – which absorbs pension funds when an employer becomes insolvent – provides a model for an alternative approach. As large, consolidated scheme of nearly £40bn run with a long-term focus rather than an eye on ceasing to exist, the PPF has retained exposure to risky assets while the wider DB universe has “de-risked” – investing around 40 per cent of portfolio in bonds relative to 70 per cent in the wider DB universe.

We suggest that the government increase the amount of DB pension assets that are invested in this way through: first, providing a specific legislative regime around superfunds, which are a way to consolidate existing DB funds as an alternative means of allowing employers to end their liabilities. That regime should allow members to benefit from the higher returns a fund generates by investing in risky assets, by allowing them to share some of the surplus created by the superfund.

Second, and more radically, the government should legislate to expand the remit of the PPF to allow it to act as a state consolidation option for solvent pension schemes, giving trustees who want the certainty associated with buyouts an alternative route.

DC and local government schemes are smaller in total but have a longer future than DB legacy schemes. The DC universe remains fragmented with almost 27,000 schemes in existence and the strategic asset allocation of LGPS remains the remit of almost 100 different local pension boards. To deliver more concentrated active ownership of UK firms, this consolidation process needs to be turbocharged so that, for example, DC schemes are big enough to invest actively and to hold shares directly.

To accelerate the consolidation of DC schemes, we recommend that the government goes ahead with setting stringent value-for-money tests, and mandates funds that fail to meet these tests to transfer assets to a number of authorised master trusts (multi-employer DC pension trusts). The government should aim for there to be fewer than 250 non-micro DC funds by the end of the decade. For LGPS, we recommend that the government announces that their £300bn of assets are pooled into one consolidated pension fund.

Together, these reforms will help to drive scale in the active pension market and, over the medium term, they will create a set of large funds able to act as blockholders of UK firms and to invest directly in unlisted, productive assets. This would deliver at least as good outcomes for savers and, crucially, significantly better outcomes for the UK economy as a whole.

Since our recommendations were published, the chancellor has announced a number of reforms focused on incentives for firms to expand and invest, which are consistent with our proposals.

Worker voice spurs investment

Compounding the lack of “owner voice” is a lack of worker voice. UK firms are unusual in Europe in having no mandatory requirement for worker representation on corporate boards. The evidence from European countries that have introduced mandatory worker representation suggests that this can support a focus on value creation in businesses. There is no evidence that it generates large pay hikes; instead, it delivers increased investment and improvements in broader measures of firm performance such as productivity, survival and job quality. This is consistent with a mechanism through which repeated interactions between workers and managers facilitate cooperation, build trust and improve decision-making for the longer term. We therefore propose the mandatory inclusion of worker representatives at the board level in larger firms.

Not only willing but able to invest

Even if firms are willing and have the finance to invest, they still have to be able to make an investment actually happen. Around half of business investment is in buildings, and much of the rest needs a building to house it. Construction is made more costly in the UK by the stringency and unpredictability of the planning system, driven by the significant degree of discretion awarded to decision-makers.

Consistent with this, the UK has actually seen no increase in the amount of built-up land per capita since 1990, and if anything, a fall this century (see Figure 3). This is in stark contrast to every other G7 economy, which not only have higher levels of built-up land per head but have seen substantial increases decade-on-decade.

Beyond direct restrictions on commercial development, the challenges of getting housing and infrastructure built combine to prevent local economic development in areas where there is demand for it, including high-tech clusters that are key for the UK’s growth prospects. Planning restrictions are also creating barriers to much-needed net zero infrastructure investment, including new onshore wind farms, new solar farms and grid connections.

To boost the construction of business structures in the UK and allow productive areas to grow, while avoiding congestion and sprawl, and protecting the natural environment, we recommend that:

- Development plans must exist and provide certainty that compliant developments will proceed.

- Plans and decision-making related to commercial and business developments should be carried out at the right level – reflecting functional economic areas.

- Local authorities should have meaningful financial incentives for development, both commercial and residential.

There are of course significant political constraints to planning reform. If national progress remains elusive, then some of these principles can be feasibly explored for combined authorities.

Additional support for smaller firms

While access to finance in the aggregate is not the leading barrier to investment in the UK, there is evidence that some smaller, high growth potential, firms suffer acutely from a lack of access to long-term capital to enable them to invest and scale. The British Business Bank (BBB) has been doing important work in this space, having developed a range of funding schemes for businesses of varying maturity across both debt and equity products, but on a relatively small scale compared with similar institutions elsewhere.

We propose that the BBB offers a co-investment fund that would allow pension funds to invest as a limited partner alongside it, piggybacking on its expertise.

For the wider set of SMEs, where the diffusion of productivity-enhancing technologies and practices is a key objective, the government should build on the existing £500mn Help to Grow framework, expanding experimentation and evaluation within the continuity of the broad programme, so that it can draw robust conclusions on the specific design of interventions that can have a positive impact on businesses.

Resources from domestic savers or overseas

If the UK succeeds in raising its investment levels, then the resources for it will have to come from somewhere, and this can only be from higher domestic savings or, through a higher current account deficit, abroad. The reforms discussed above will make the UK more attractive for foreign direct investment and other forms of external financing, but policymakers should also aim to finance part of the increase with higher domestic saving.

The UK’s national savings rate is extremely low – the second lowest in the OECD, and the savings rate of UK households is so low that, once they have invested in housing, no funds are left for net investment in businesses. The only savings policy that has had a material impact on UK households’ saving rates in recent decades is the introduction of auto-enrolment, which has seen the share of workers saving for a pension rise from 47 per cent in 2012 to 77 per cent in 2019.

We recommend a phased increase in the minimum savings rate within autoenrolment, specifically by levelling up the minimum contributions by both employers and employees to 6 percentage points, a 50 per cent increase in the total and enough to finance a “Living Pension”. This would raise aggregate savings in the UK and also help to address the separate problem of widespread insufficient saving for retirement.

Stable and strategic growth policy

These policies will only work if they persist and are expected to persist. One way of trying to achieve greater policy stability is through strengthening the institutions that govern growth policies. We propose a new Growth Act to establish an independent statutory body, the National Growth Board, which would report to the Cabinet Office.

This body would build on the previous Industrial Strategy Council but be broader in scope and more permanent in nature. Transforming the ecosystem for business investment in the UK will be arduous and complex, but it is necessary to return the country to sustainable growth in living standards. The reforms set out above will not be the end of the story and must be enacted along with the overall strategic change that the Economy 2030 Inquiry recommends. But taken together, they will move the UK from living off the past to investing for the future.

- This article is reproduced with a different title from the Autumn 2023 issue of CentrePIece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance. It summarises ‘Beyond Boosterism’ published by CEP and the Resolution Foundation.

- The Economy 2030 Inquiry is a collaboration between CEP and the Resolution Foundation, funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image courtesy of DesignRaphaelLtd,, All Rights Reserved

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.