When a product is launched, sales increase for about a year, then decline steadily. The pipeline keeps moving, with newer, more innovative products reaching the market. David Argente, Munseob Lee and Sara Moreira examined the dynamics of product sales throughout their life cycle. They write that the constant turnover of products and competitive pressures keep firms on their toes and the resulting innovations contribute to economic vitality.

If you are an attentive consumer, you might have noticed that products don’t last very long in the market. New products, whether by the same firm or its rivals, will be waiting in the pipeline to take their place. Firms who don’t introduce innovations risk losing market share as their products become obsolete fast. This constant turnover in product lines plays a key role in keeping the economy alive and kicking.

In our recent study, we examined the complex dynamics of product sales throughout their life cycle. We used highly granular retail-scanner data from Nielsen, an analytics firm covering non-durable and semi-durable consumer goods such as food, drinks, health and beauty care products. The data allowed us to track the introduction of new products in the United States using manufacturer barcodes, and measure their performance, while keeping track of the entire portfolio of the manufacturing firm and its competitors.

Our main finding is that after a brief period of increasing sales that lasts approximately a year, most products see steadily declining sales throughout the remainder of their life cycles. Sales drop, on average, 30 per cent per year between the first and fourth year of activity. This pattern holds qualitatively across many different types of products, including long-lasting superstar products, and is driven by reductions in quantities sold, rather than by reduced prices.

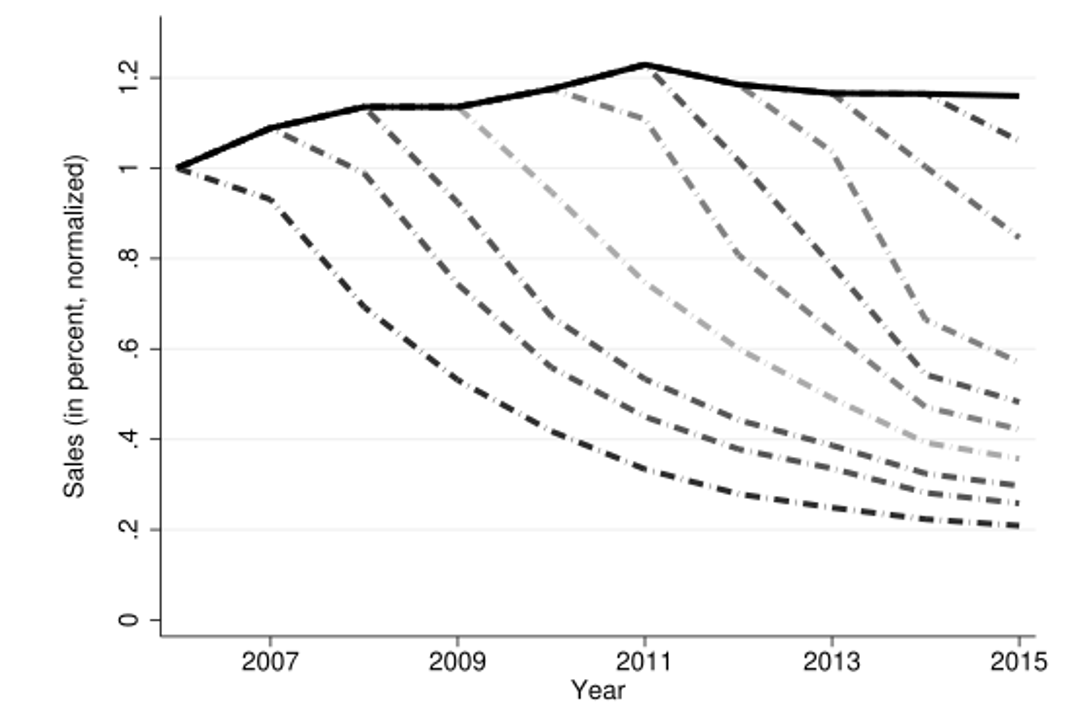

To illustrate this pattern, we plot the sales of one of the largest firms in our dataset in Figure 1. The solid line represents the evolution of total sales, which grew from 2006 to 2015. Each of the dash-dotted lines shows the evolution of sales for the products introduced up to each of the periods. The first line on the left, for instance, represents the path of sales of products that existed in 2006 – products that entered the market subsequently (2007–15) are not added. For this firm, more than 80 per cent of 2015 sales came from products introduced after 2006. This firm’s smooth and moderate sales growth per year conceals massive product reallocation. A large share of sales is generated by new products and a large share of reductions in sales is generated by older ones.

Figure 1. Evolution of a firm’s sales by cohort of products

We examined the fraction of each manufacturer’s total sales coming from newer and older products and we found patterns similar to those in Figure 1. This finding is somewhat surprising if we consider that sales of older products should increase as firms push products into more stores and consumers gradually adopt them.

So why do sales of older products sag? Do companies realise those products are not very good and axe them? Or do consumers lose interest over time? We find that most products reach their apex very quickly and sales usually begin declining after about a year or two, until eventually they are axed by firms. This decline in sales is due to products gradually becoming less appealing compared to newer, more innovative offerings by the same company or by its competitors.

It turns out that as consumers, we are not very loyal creatures. We may purchase the same brand of toothpaste that we did a decade ago, but we probably updated to a new flavour or formula with improved health benefits. Or maybe we switched to a competitor brand because its new look or flavour struck our fancy. We use our data to measure these two elements: “business stealing,” where competing firms introduce similar but more enticing new products; and “cannibalisation,” where firms introduce new versions of their own products, thereby reducing the attractiveness of their older products.

These two elements create a never-ending loop of innovation and obsolescence. When competitors introduce new products, your once-favourite product loses its appeal, and firms rush to innovate again, rendering its older products even more obsolete. It’s a cycle that keeps the market on its toes and shapes the fate of our beloved products.

Building on these insights, we developed a model that captures a behind-the-scenes look at the game of innovation and obsolescence. Firms find themselves in a tight spot – introducing new products is essential for growth, but it also speeds up the decline of existing ones. It’s a delicate balance, and the model captures this tug-of-war between internal and external innovations. The model predicts an innovation-obsolescence cycle, where firms innovate internally to keep up with the external innovations of competitors. The interplay between these two types of innovation shapes the growth of firms and, consequently, the economy.

The study gives us a peek into the dynamics of the products we love as consumers. It’s not just about the thrill of a new purchase; it’s about the constant churn and evolution happening behind the scenes. Our headline finding that the sales of individual products decline throughout most of the life cycle suggests that an arms race to introduce the most appealing and consumer-enticing products is a hallmark of firm competition across a wide variety of sectors.

Our previous study used the same dataset and found that product entry and exit declined by 25 per cent during the Great Recession from 2007 to 2010. These missing years of new products were an important factor in the slow recovery the economy experienced after the crisis. When consumers came back to stores years after the recession, they found fewer new and better products on the shelves.

In conclusion, our research provides insights into the complex relationship between product life cycles, firm growth and market competition. It offers a comprehensive view of how firms’ innovation strategies are essential for maintaining economic vitality amid the constant turnover of products and competitive pressures. We believe these insights will be valuable to policymakers and business leaders as they navigate the challenges of encouraging innovation while managing the unavoidable obsolescence that accompanies it.

This blog post is based on “The Life Cycle of Products: Evidence and Implications” Journal of Political Economy.

- The post represents the views of the author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Featured image provided by Shutterstock.

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.