Lex Dinamica is a boutique consultancy offering tailored data privacy solutions to clients. As well as running a skills seminar with us next week, they share exclusive industry insights with us in this guest blog.

Growing use of artificial intelligence in recruitment processes

Artificial intelligence (AI) scales well, its labour is relatively cheap, and it promises the kind of objectivity and consistency that should have every equal opportunity employer rushing to adopt it in their company. And many have.

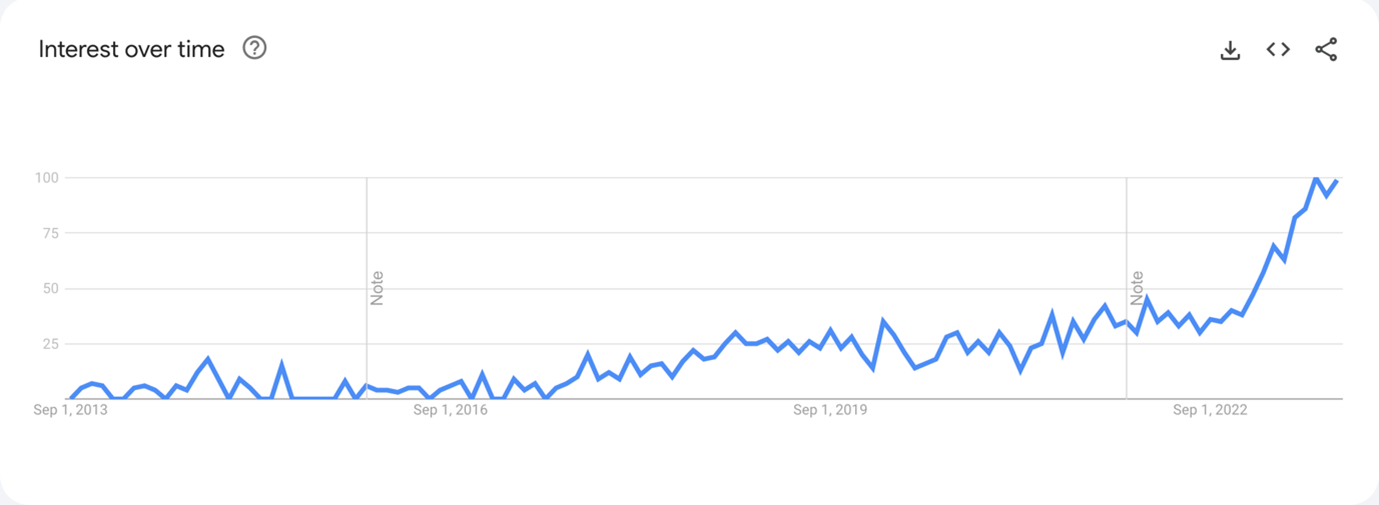

GoogleTrends for “AI in recruitment” worldwide, over the last 10 years

There is a large and still growing number of use cases for AI in recruitment – from personalised outreach based on candidates’ behaviour on the company website, to analysing video interviews to assess a candidate’s cultural fit based on their word choices, speech patterns, and facial expressions – every stage of the recruitment process has been permeated by AI. AI systems can also use sentiment analysis to detect language likely to decrease engagement with job postings, source candidates from social media profiles, help to develop insights on past candidates who were successful at a company, and auto-screen resumes. At each of these stages and in every use case, they have access to large amounts of jobseekers’ data.

Candidates share lots of personal information with potential employers during the recruitment process. They at least share their information that identifies them (names, application numbers), contact details (email address, phone number), educational history, employment record, the languages they speak, and special skills they possess. Not all applications of AI to this data are legal, and the circumstances under which AI use is permissible are closely regulated under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

We’ll now explore in more detail how personal data and data privacy regulations are involved in three AI use cases: the sourcing of candidate data from social media, auto-screening CVs, and video interview analysis. Firstly, we’ll talk about legal basis for data processing, the restriction on automated decision-making under Article 22, and concerns about algorithmic bias in AI systems. Then finally, we’ll briefly touch upon what candidates can do about how their personal data is used in recruitment processes and how the EU AI Act might come to change the regulatory landscape in this area.

Legal basis of processing

As with any processing activity involving personal data under the GDPR, the recruitment company will need a legal basis to use AI on candidates’ information. The most likely suspect for sourcing candidates is the legitimate interest basis, which allows for processing to the extent to which it “is necessary for the purposes of a legitimate interest pursued by the controller or a third party.”[1] Recruitment agencies might have trouble asserting that it is necessary for them to peruse people’s private social profiles, on platforms such as Instagram or Facebook, since such profiles are unlikely to contain information related to business or professional purposes. The Article 29 Working Party guidance on data processing at work affirms that whether data is relevant to the performance of the job for which the candidate is being considered is an important indication of the legality of the collection.[2] It seems, therefore, that our Facebook data from back in 2010 should not make it onto anyone’s candidate database. On the other hand, data from professional networking platforms, such as LinkedIn or Jobcase, should be in scope.

For auto-screening candidate resumes, as well as for video assessment software, the most likely legal basis for processing will be explicit consent or necessity for entering into a contract that the data subject wishes to enter into. Auto-screening usually entails having an AI system go through the content of resumes to determine to what extent a feature, or a set of features (profile) that the company is looking for is present. That’s why you may have heard advice about putting the names of top universities or key words from the job description on your resume in white font – to trick the auto-screening software. Video-assessment software uses AI to evaluate the body language, facial expression, and speech patterns in the recording. Both technologies are applied to data submitted by candidates themselves, so it is possible for the recruitment company to obtain explicit consent through the application form before any processing takes place – this will be relevant for the restrictions to the use of automated decision-making and profiling under Article 22 GDPR.

Automated decision-making under Article 22 GDPR

Article 22 of the GDPR provides individuals with a right to not be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling.[3] As an exception, such decisions are permitted where necessary for entering into a contract between the data subject and the data controller, where authorised by law, or based on explicit consent. Therefore, there are several ways to use AI in recruitment while staying compliant with the law.

The simplest way is for the recruiter to make sure to keep a human in the loop – Article 22 applies only to decisions and profiling based solely on automated processing. If the decision or the profile is at some point reviewed by a human, it’s possible that the article and its protections may no longer apply in that instance. For example, if the software sources a list of candidates for a position based on a profile compiled by the recruiter (which likely makes it profiling), but then an employee goes through the list choosing for some to be contacted and some to be rejected, that does not fall within the scope of the Article 22 restriction.

If the recruiters do not wish to keep a human in the loop, they will need to rely on a different legal basis: necessity for entering into a contract, or explicit consent, and if there is processing of special categories of data – race, ethnic origin, political opinion, trade union membership[4] – only explicit consent will be sufficient.

It’s therefore relevant what data is processed in the automated decision-making. That can be relatively self-explanatory in case of CV screening, but it becomes more difficult with sourcing and video assessment. Those systems have access to images of the candidates which may reveal more data and special category data, that would likely not be included in their resumes: almost certainly race and ethnic origin, and possibly religious beliefs, health status, and even sexual orientation. Because of anti-discrimination regulations, Recital 71 of the GDPR, and the phenomenon of algorithmic bias, it’s quite important to know how an AI makes its decisions, and it becomes doubly so if it has access to data on which we don’t want it to base decisions.

Algorithmic bias

Algorithmic bias describes systematic errors in a system that create undesirable – unfair – outcomes, such as arbitrarily privileging one group of people over another. A central case of algorithmic bias in a sourcing scenario would be disfavouring foreign sounding names,[5] for example Akiyo doing better than Agatha in Japan, or Joe doing better than Jose in the US, when both candidates have the same qualifications. Algorithmic bias can result from biases in the programming but is more often caused by biases within the data used to train the AI. If a company has historically been more likely to hire men over women, a system trained on past hires could end up favouring men due to pattern recognition and replication, without being explicitly instructed to make decisions based on gender. In fact, even if instructed specifically to disregard the gender column in the data table, by pattern-matching all other attributes of a profile, an AI could end up privileging male candidates.[6]

This is a significant worry in the context of recruitment, partly because it goes against the interests of the company to miss out on the best candidate out there due to bias, partly because it’s discouraging and harmful for candidates to be assessed on aspects other than their qualifications for the job, and mostly because it’s unethical and unlawful under non-discrimination laws. The unfortunate news is that explainability – the feature of an AI system describing how capable humans are of understanding and explaining its decision processes – does not currently seem to be a priority among AI developers.

With the recent popular successes of huge neural networks – Stable Diffusion, ChatGPT – the trend seems to be towards more data, more parameters, and more compute power, for better results at the price of less insight into how they’re achieved. This is problematic in the EU considering Recital 71, which requires that in cases where there is processing involving automatic decision-making, the data subject be given “specific information” and have a right to “obtain an explanation of the decision.” There isn’t yet much clarity on what level of detail the data subject is entitled to – is it enough to inform them of the data elements that the decision was based on, or would the AI company need to be able to specify what exactly the candidate could change to change the decision? A CJEU judgement in Schufa,[7] expected late this year or early the next, could provide more clarity on the interpretation of the provisions.

Takeaways for jobseekers

Recruiters using AI for sourcing candidates from social media can benefit both sides of the interaction: it gives head-hunters a larger pool of candidates and better chances of finding the right person for a job, whereas jobseekers can be presented with options that they didn’t have to look for. However, if you don’t like that arrangement, there are some things you can do to unsubscribe.

As we’ve seen before, it is generally easy to make candidate sourcing legal at first glance, so you’ll have to be a little proactive, rather than waiting to be prompted about your preferences. In this, privacy settings on your social media will be your best friends: choose carefully what you’re willing to share, and with whom. If you choose to continue existing on the internet, when contacted by a recruitment person, check the message for a link to the privacy notice – they’re under an obligation to inform you of several aspects relating to their processing of your data, and the easiest way to discharge that obligation is by adding a link to their online privacy notice in the email footer. In the privacy notice, they’ll inform you of your rights as a data subject, including the right to erasure and the right to object to the processing of your data. By exercising them, you will put an end to the processing of your data.

If you do wish for your data to be processed, but you don’t trust the outcome of automated decisions, seek human review by emailing the HR department or the DPO. If you exercise this right, the HR team will go ahead and review your application to check whether their AI made the correct decision in (presumably, since you’re questioning it) rejecting you.

In a few years, when the EU AI Act comes into force, the regulations around the use of AI in recruitment will change a little in Europe; however, those changes should not extend to jobseekers’ rights. Under the current proposal, AI systems used to recruit and select job candidates by screening and evaluating their applications (Annex III 4.a) are classified as high risk, which means that require that the deployer comply with certain conditions and perform a conformity assessment. The new rules will certainly increase the compliance burden on employers wishing to use AI solutions in recruitment processes, but their impact on the realities of job applications from the perspective of the candidate should be minimal.

It is currently the case, and will likely remain so in the near future, that avoiding having your publicly available data collected for recruitment purposes is essentially impossible. With a little bit of effort, though, it is possible to object to the processing of your data after the collection, and have the processing cease. Whether this is a satisfactory compromise between giving data subjects control over their data on the one hand, and allowing recruitment businesses to pursue their interests on the other, is open to discussion.

More about Lex Dinamica

Lex Dinamica is a boutique consultancy offering tailored data privacy solutions to clients – anything from responding to data subjects’ rights requests, to designing and implementing Data Privacy/AI/Ethics Governance Frameworks. Our team of experienced privacy professionals combine legal acumen, operational experience, and technology to offer solutions that are fit-for-purpose and built to last.

Enjoyed this blog? Head to CareerHub to book your place on next week’s event: Skills Seminar – Data Privacy with Lex Dinamica.

[1] GDPR, 6(1)(f) “except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject which require protection of personal data.”

[2] Opinion 2/2017 on data processing at work, p. 11

[3] GDPR, 22(1)

[4] GDPR 9(1) (link to website with Art. 9: https://gdpr-info.eu/art-9-gdpr/

[5] https://hbr.org/2019/10/what-do-we-do-about-the-biases-in-ai

[6] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight/amazon-scraps-secret-ai-recruiting-tool-that-showed-bias-against-women-idUSKCN1MK08G

[7] https://curia.europa.eu/juris/liste.jsf?num=C-634/21