- The Colombo Port City is a microcosm of how China has rapidly gained an economic foothold in many nations, swaddled within the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and has been referred to as “a nest to accommodate the Phoenix”.

- A comparative analysis with Djibouti serves to highlight the long-term strategic implications of Colombo Port City, such as the potential for asset seizure for hybrid dual-use models with People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN) expansion.

- Beijing’s financial muscle in Colombo is to thwart US Indo-Pacific ambition and reduce Indian influence. China’s posturing would open up the nation to a geopolitical battleground.

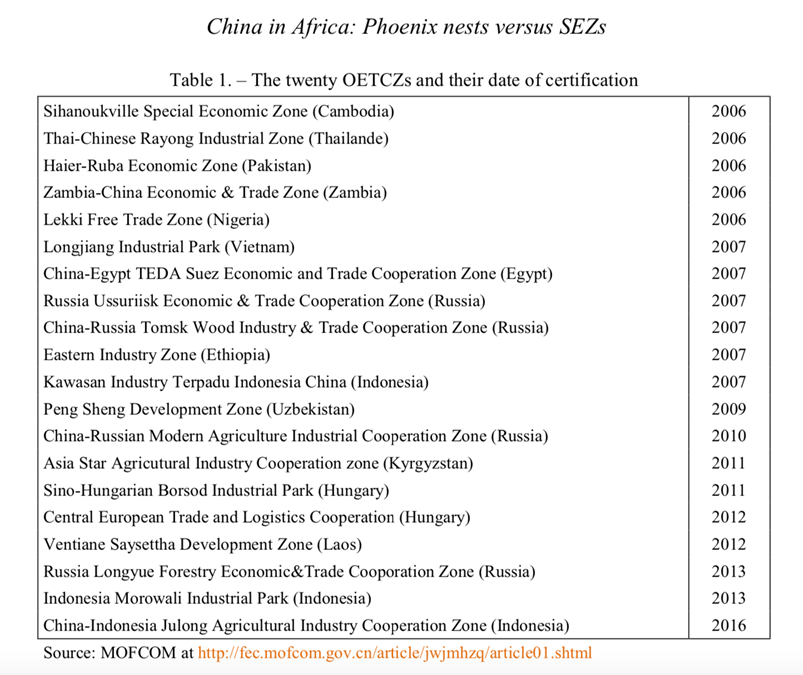

Sri Lanka is in a conundrum. Its present governance has approved China’s extra-jurisdictional Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Colombo Port City, right next to its commercial port. The Colombo Port City is a microcosm of how China has rapidly gained an economic foothold in many nations, swaddled within the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). SEZ or Overseas Economic and Commercial Cooperation Zones (OECCZ) are the primum principium of ‘building a nest to accommodate the Phoenix’, according to Lin Yifu, Chief Economist and former Senior Vice President of the World Bank. It was Lin Yifu who convinced former Ethiopian President Meles Zenawi and submitted a report to Omar Guelleh, the President of Djibouti, to follow the OECCZ model. Have all these Chinese OECCZ in Africa and elsewhere considered the host countries’ needs? The 20 zones already established (refer to the table below) raise questions about the degree of contribution to the host nation.

Colombo Port City

“This is a new PPP model, this is not a Chinese project, this is an international project, we will have international developers, we are willing to joint venture with Indian and US companies,” said Houliang Jiang, Managing Director of Colombo Port City, who was interviewed by this author on 22 February 2019. During the interview, the biggest concern raised by Houliang was the delay of the government: “Government is far behind.. we are ahead of schedule…the government have not given land title and no favourable investment climate… we provide the world-class infrastructure, the ‘Hardware’ part, but the ‘Software’ part, the policy part, is missing so how to do this project?”. Unlike the previous regime, the Rajapaksha administration approved the missing ‘Software’ component from a Port City Bill on 23 March. A backchannel was in motion taking the bill forward during the Sinhalese and Tamil New Year’s Day.

Government party MP Wijedasa Rajapaksha accused the government of creating a “Chinese colony and foreigners can acquire that land and sell it”, explaining further that the former government had given the Chinese-built Hambantota Port for 99 years and handing over the Port City to China through an act would be more dangerous than the Hambantota port. 20 petitions were filed in the Supreme Court from all major opposition parties and civil society activists, challenging the constitutionality of the Port City Bill and its threat to Sri Lanka’s sovereignty. Ikram Mohammed PC appeared for the Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL), arguing that the Colombo Port City Bill ‘paves the way for the creation of a federal state’. Whether the bill transfers presidential powers to an unknown commission to bypass the country’s financial regulations in place is a vital and relevant question raised by the petitioners. The Port City Bill would serve to set up Sri Lanka’s first OECCZ with special jurisdictional rights separate from existing laws. This unique Chinese model has been introduced in many nations to create jobs and foreign investment as a ‘nest to attract the Phoenix’.

While the Rajapaksha’s political party (SLPP) supported trade unions, it rejected development projects such as the US Millennium Challenge Compact (MCC) grant of USD 480 million and recent swapping of East Container Terminal (ECT), projected as a threat to sovereignty playing with the high nationalist sentiments to their voter base. The same administration does not see any threat to the island’s sovereignty from the Chinese port city. This is a clear indication of Rajapaksa’s China-bandwagoning foreign policy. There are several reasons for the recent China tilt. First, high-level diplomatic visits reaffirming the success of the Chinese political model during the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) centenary, from last October 2020 with Senior Ambassador Yang Jiechi’s visit, followed by China’s Minister of Defence General Wei Fenghe’s visit this April, have strengthened the Sino-Lanka diplomatic and security relationship. Second, China’s open UNHRC support for the Rajapaksa regime. Third, China’s vaccine diplomacy in Sri Lanka let “Sri Lanka and China build a great wall of vaccines”, explains the Chinese Ambassador in Colombo Qi Zhenhong. Fourth, the recent loans of USD 1 billion as well as a USD 1.5 billion currency swap where Sri Lanka, a weaker economy, is already shackled by a heavy Chinese economic grip. These incremental shifts in the Sino-Lanka relationship have increased alignment towards China under the Rajapaksha regime.

The importance of the Colombo Port City project was discussed between President Gotabaya and President Xi during their last telephone conversation. China will use Sri Lanka’s inner politico-social weakness, such as inadequately addressing human rights issues, to its own advantage as China has no concerns in this regard. While China pushes its BRI agenda, the welcoming ‘pull factor’ from the Gotabaya Rajapaksha regime is positive. The same pull factor of inviting China was seen during the Mahinda Rajapaksha era which inaugurated the Colombo Port City in 2014. The Sri Lankan strategic community would need to deep dive and assess the long-term strategic implications from the new Chinese PPP model, as Colombo Port City development is expected to take more than 25 years. A comparative analysis to Colombo Port City is to explore Djibouti, as both nations welcome the Chinese model.

Djibouti SEZ

Like Sri Lanka, the Horn of Africa on the Gulf of Aden and the Bab-el-Mandeb at the southern entrance to the Red Sea in Djibouti are geostrategically well-situated. The 23,200-square-kilometre nation is already What attracted the Chinese was Djibouti’s geography. China’s large scale infrastructure development connected neighbouring landlocked Ethiopian trade from Addis Ababa, Africa’s first fully-electrified transnational railway that stretched 752-km railway to Djibouti port. Multiple loan packages shackled Djibouti’s economy in Beijing’s strategic direction. Given its import dependence and above 70 percent service sector, logistics and transshipment have become a lucrative new market for Chinese exports. One of the clear ingredients in the Sino-Djibouti cooperation projects in the Horn of Africa is Chinese Special Economic Zones. China has helped launch the first phase of Africa’s biggest free-trade zone, Djibouti International Free Trade Zone (DIFTZ), a USD 3.5 billion project that spans an area of 4,800 hectares . The USD 370 million, 240-hectare pilot zone is led by a global alliance including DPFZA, China Merchants Group, Dalian Port Authority and IZP Group. The DPFZA already offers 100 percent foreign ownership, full exemption from direct and indirect taxes, 100 percent repatriation of capital and profits, no currency restrictions and flexible recruitment laws.

Most of Djibouti’s 14 major infrastructure projects, which have been valued at a total of USD 14.4 billion, are being funded by Chinese banks. On 27 January 2014, China and the Djibouti government signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) to build a special economic zone aspiring to the success models of Shenzhen and Shanghai. The government wished to build Djibouti into an African version of Singapore and Hong Kong by creating this SEZ with extra-jurisdictional rights and tax incentives. Touchroad, the Chinese multinational group that engaged in this operation, has promised the SEZ to be different from a regular development zone or industrial park, more like a fully functional port city with residential areas, hospitals, schools, shopping centres and office facilities, which promises the locals thousands of jobs just like in Sri Lanka. Since Touchroad has already obtained the land and special administrative rights, it bypasses the Djibouti government approval process, a similar factor to Colombo Port City. Touchroad Djibouti Special Economic Zone will function as a Chinese special territory leased out for 99 years in Djibouti, catering for the Chinese market and Chinese exports to Africa. President Xi’s new ‘dual circulation’ economic model needs new markets. The Chinese PPP model in Djibouti and Sri Lanka will help Xi’s ‘dual circulation’ model, flooding Chinese imports rather than increasing local exports. Many African SEZs have failed to deliver what was promised. An assessment of failures and challenges the other SEZs faced would help nations like Sri Lanka who have accepted the Chinese PPP model in amending their laws to fit the model.

Military dimension

Not limiting itself to economic development, months after opening the Chinese-funded SEZ, China established its first overseas military base for USD 20 million a year, sitting closer to the foreign multi-base operation. China justified its military base in Djibouti as its international obligation to achieve stability in the region. The economic gains and local jobs is one side of the coin. The other is the strategic dimension of China’s geopolitical influence towards such nations, in the long run, turning economic development into asset seizure for hybrid dual-use models with People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN) expansion. China’s economic and strategic intent in Djibouti and Sri Lanka is outsized. China is testing its economic influence to advance its security interests with a hybrid model of stealth and precision. Sri Lanka is a well-positioned island for international counter-piracy operations. In the China-US-India maritime power triangle China wishes to adopt the strategy of “careful selection, low-key layout, cooperation first, and slow penetration” to gradually promote the expansion of China’s sea power in the direction of the Indian Ocean, according to an article from PLAN-affiliated Chinese Naval Research Institute. The slow penetration to establish Chinese presence has a higher degree of success after Hambantota, while assisting the ailing Sri Lanka economy is a priority. Beijing’s financial muscle in Colombo is to thwart US Indo-Pacific ambition and reduce the Indian influence. China’s posturing would open up the nation to a geopolitical battleground.

Just as China justified its military base in Djibouti as its international obligation to achieve stability in Africa, there are clear signs it could transform its development port projects in the island nation for dual-use to achieve stability in Indian ocean waters. It’s time Sri Lanka calculates the geopolitical implications before building the “phoenix nest”.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the China Foresight Forum, LSE IDEAS, nor The London School of Economics and Political Science. This article was originally published by the Observer Research Foundation on 1 May 2021.