Cecilia Han Springer

China can become a global green leader by channelling overseas support for infrastructure and development towards a clean energy transition.

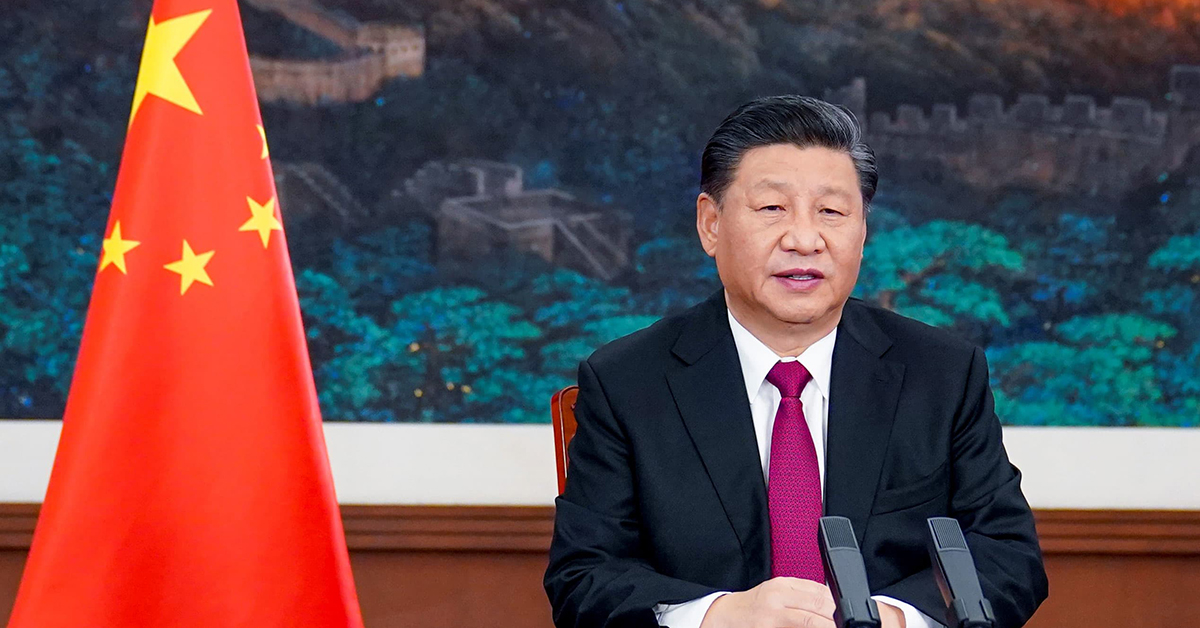

The country has already built momentum in this regard, with Xi Jinping’s announcement at the 76th United Nations General Assembly that China would not build new coal-fired power projects abroad. Ending such support not only has real climate and environmental benefits, but also demonstrates symbolic leadership that hopefully inspires other countries to follow suit.

Since the Paris Agreement was struck in 2015, China has approached its climate policy formulation with consistent rhetoric, linking decarbonisation and structural economic transition for domestic climate efforts. Xi’s announcement expands this rhetoric to include China’s overseas activity, arguably the most high-level, high-profile, and specific commitment yet related to greening the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Rhetoric opens up space for accountability, and while the details are not yet fully clear, host countries and civil society can now play a role in ensuring the announcement is translated into policy.

With China restricting support for overseas coal plants, other countries and institutions supporting coal can no longer hide in China’s shadow. Since 2011, when the World Bank first restricted overseas finance for coal plant development, there has been a consistent domino effect as an increasing number of countries, development finance institutions, and banks have adopted similar policies. As the largest public financier of coal, as well as a developing country, China’s announcement sets a precedent for remaining countries publicly funding coal, most of which are in the developing world. In addition, because Xi’s announcement will likely include public and commercial finance (as evidenced by Bank of China’s subsequent commitment), the focus should now turn to private sector coal support, which represents the majority of coal finance in recent years.

Ahead of the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), China can take this announcement a step further by pivoting from anti-coal towards pro-renewable energy in its overseas engagement. The buildout of renewable energy needed for developing countries to meet their Nationally Determined Contributions as part of the Paris Agreement represents an $800 billion opportunity, and China is well-poised to take advantage.

China already plays a role in enabling renewable energy development overseas. China’s financing for clean power generation increased more than fourfold from 2015 to mid-2019. China also possesses the technical expertise and manufacturing capacity to enable the full suite of technologies necessary to promote renewable energy penetration, from generation capacity to transmission infrastructure, grid upgrades and energy storage. Xi’s announcement also stated China would “step up support for other developing countries in developing green and low carbon energy,” and more specific policies, plans, and commitments to this would demonstrate real global leadership.

In all, the no-coal announcement could herald a major shift in greening the BRI. From rhetoric to specific policies, the pieces are in place for China to operationalise a commitment to overseas clean energy development. Doing so would demonstrate truly global and green leadership.

Nicholas Stern and Chunping Xie

China has made remarkable achievements in economic development ever since its reform and opening-up strategy was launched in 1978, with the country transitioning from low-income to upper-middle-income status and hundreds of millions rising out of poverty. However, strong economic expansion has highlighted pressures on the environment, and heavy investments in physical capital fuelled by the extensive use of fossil fuels and materials have led to mounting threats to natural, human and social capital.

Over the last decade, China has increasingly recognised the urgency and importance of environmental issues in lives and livelihoods within the country, and its attitude towards environmental policies and climate change has changed significantly – from participating in international action on climate change to increasingly taking on a leadership role in global environmental governance.

China’s 12th Five-Year-Plan (2011-2015) dedicates a whole chapter to climate change, with the transition to a low-carbon economy being a central priority. The 13th Five-Year-Plan (2016-2020) strengthens China’s commitment to climate change through broader environmental and efficiency targets. China has been stepping up efforts to tackle climate change and environmental pollution, irrespective of the steps taken by other countries, including when President Trump announced the intention to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement in June 2017.

In September 2020, before the election of President Biden, President Xi Jinping declared at the UN General Assembly that China will aim to become carbon neutral before 2060. This significant pledge further underlines China’s commitment on climate action, shows China’s climate leadership, and sends a clear signal to other countries that the COVID-19 pandemic should not prevent more ambitious action to tackle climate change.

Though coal is still dominating China’s energy mix – with a 61% share in 2019 – China is leading the world in renewable energy production. China accounts for about half of the world’s total installed capacity (Climate Transparency), and China is the world’s largest investor in renewable energy, at home or abroad (Center for Strategic and International Studies). President Xi has announced that China will stop building new coal-fired power projects abroad.

To accelerate the energy transition, China has been implementing strict regulation of “dual-high” projects – those with high energy consumption and high greenhouse gas emissions. Its recently released new set of instructions on improving its “dual-controls” goals, namely the energy intensity targets and caps on total energy consumption, specify that the portion of renewable generation exceeding the obligatory renewable electricity quota can be exempted from the total energy consumption cap, which could greatly encourage further deployment of renewables.

China is also leading in Energy Vehicles (EVs), with the world’s largest EV market and is at the forefront of the development of EV battery technologies. As its EV industry advances with strong policy support, economies of scale and increased competition have rapidly driven down the costs and stimulated technological innovations.

Covering the electricity sector which is responsible for roughly 40% of China’s total emissions, the recent launch of the national emissions trading scheme (ETS) marks a significant step towards the country’s carbon neutrality pledge. Though the current carbon prices are at a level too low to have major impact on incentivising the low-carbon transition, the mechanism which is now in place could play an important role as climate ambition and action build.

China has linked the low-carbon transition with the country’s sustainable development strategy and long-term prosperity, which is framed within the concept of “Ecological Civilization”. China recognises both its size in terms of emissions and its great vulnerability to the impacts of climate change, from disruption of water flows from the Himalayas, extremes of heat, cyclones and storm surges with so much of its population coastal.

China has a great deal to gain by being in the vanguard of the new global growth story, driving growth internally and with strong export markets and stimulus of greater investment in green areas.

All this being said, China’s emissions are not yet falling. It has reacted to the current world gas and oil shortages by increasing coal production. Bringing forward the peak in China’s greenhouse gas emissions to no later than 2025 (i.e. within the 14th Five-Year Plan), is crucial for China’s own climate goals and for the world as a whole, and will establish itself as a true leader for the 21st century.

Erik Solheim

The first time I visited China, in 1984, China was poorer than most of Africa. There were no private cars, no high-speed rail and just one metro line. When reforms started, China ranked 177 on the list of nations measured in GDP per capita. No living being could fathom the transformation that lay ahead.

Now China is among the most modern nations on the planet, a leader in high-tech and soon to be a high-income country. It has declared complete victory in the fight to bring every Chinese person out of extreme poverty. China hosts 40,000 km of green high-speed rail. The US runs exactly zero.

China, with nations like South Korea and Singapore in front of them and Vietnam close behind, has pulled off the fastest development for the biggest number of people at any time in human history.

China and East Asia responded adeptly to the greatest challenge of the 20th century – development. Can China be as important to the greatest challenge of this century – the establishment of an ecological civilisation?

I am confident the answer is a resounding yes.

It is already well known that China is the world leader in nearly all technologies critical to the green shift. Silicon Valley may still be ahead of China in specific high-tech areas. But China is leading in taking green technologies to scale. China provided half of solar power in the world last year. It is by far the biggest producer of wind energy and is leading the world on green hydrogen. 70% of all high-speed rail is running on Chinese tracks and 99% of all electric buses are travelling on Chinese roads. China was 40% of the global market for electric vehicles in 2020.

At the turn of the century China hardly had metro systems. Now the Beijing and Shanghai metros are by far the two biggest in the world and more than 35 Chinese cities run effective, clean and cheap metro systems.

The Belt and Road program provides a great opportunity for China to share its technologies with other developing countries and to provide green investments in everything from solar power to green rail. The promise by president Xi to stop all Chinese investments in coal overseas, lay the ground for a massive green sprint. We in the West better get up early in the morning if we want to compete.

Even more interestingly, China is now a global leader not only in green technologies but as well in best green practice.

Consider the city of Shenzhen as an inspiring example. In 1980, the city did not even exist; it was a fishing village. Now, not only is Shenzhen one of the most prosperous cities in the world – it is also one of the greenest. It runs 16,000 electric buses, more than in the entire world outside of China combined, and 20,000 electric cabs. There are electric trucks at construction sites. Shenzhen also has some of the greatest green corridors in the world, forming a line of defence against pollution and driving housing prices into the skies. Wetlands, hosting critical bird habitats, are integrated right in the centre of the city.

River clean-ups in Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces have brough spectacular improvement in water quality in record time. Rivers which in the past were named “milky rivers”, due to pollution not health, are now so tempting and clear that local people can bathe, children can play and retired people go for a nice afternoon walk. Local tourism has skyrocketed.

Chinese cities ten years ago rightly had a reputation for horrible air quality. Today air pollution in Beijing or Shanghai is well below many European cities and just a fraction of Indian city pollution. Determined action by the ministry of Ecology and Environment has borne fruits.

In his speech to the recent Kunming conference on biodiversity, president Xi Jinping promised to establish a new network of national parks protecting key endangered species. He established a Chinese sponsored fund for global protection of nature and promised that China will plant trees covering an area the size of Belgium every year from now to 2030.

The Chinese redlining system is global best practice to protect Mother Nature. It offers a scientific approach to providing conservation status to green hotspots in densely populated areas such as the Pearl River Delta or the lower Yangtse. Its easy for most nations, like my own Norway, to conserve far away mountains. Our real challenge is to protect nature where its most threatened, close to centres of great human habitation.

China is already a global green leader at home, even if this may not yet be fully understood by the West. But can China lead the world?

The Chinese leadership has made up its mind. It will push fast for an ecological civilisation. “Green is gold”, as president Xi says.

Still, Chinese leadership comes with some handicaps. China doesn’t have the recent experience of global diplomatic leadership like the West. It is, unlike the West, not a missionary nation. China is more like Frank Sinatra – “I did it my way”. The Chinese understands well that their many thousands of years as a strong, meritocratic state, now organised in the form of the Chinese Communist Party, cannot easily be replicated around the globe. The strength and size of China’s culture and economy may turn off partners.

But China is an indispensable partner for the West. Whatever Europe and America want to achieve – pandemic response and peace, economic growth and trade, fighting climate change and saving Mother Earth – depends upon a close partnership between China and the west.

We in the West would do well spending a little more time improving upon our own systems of government, and a bit less on criticising the systems of others. Our system of democratic Government is challenged from the inside, not from competing systems.

There will for sure be frictions between China and the West in the years to come. But we need a geopolitics of common prosperity and action. Competition and cooperation must go hand in hand.

If a geopolitics of shared humanity is established, China would be able to draw upon positive lessons from our achievements in the West. The world will learn from China and benefit from Chinese investments. The silly and dangerous idea of global decoupling will make us all into losers. When working together, only the sky is the limit.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the China Foresight Forum, LSE IDEAS, nor The London School of Economics and Political Science.

1 Comments