- The sharp decline in China’s growth rate this summer faces the leadership with a major political, as well as economic, test after almost half-a-century in which expansion has been the bulwark for Communist Party rule.

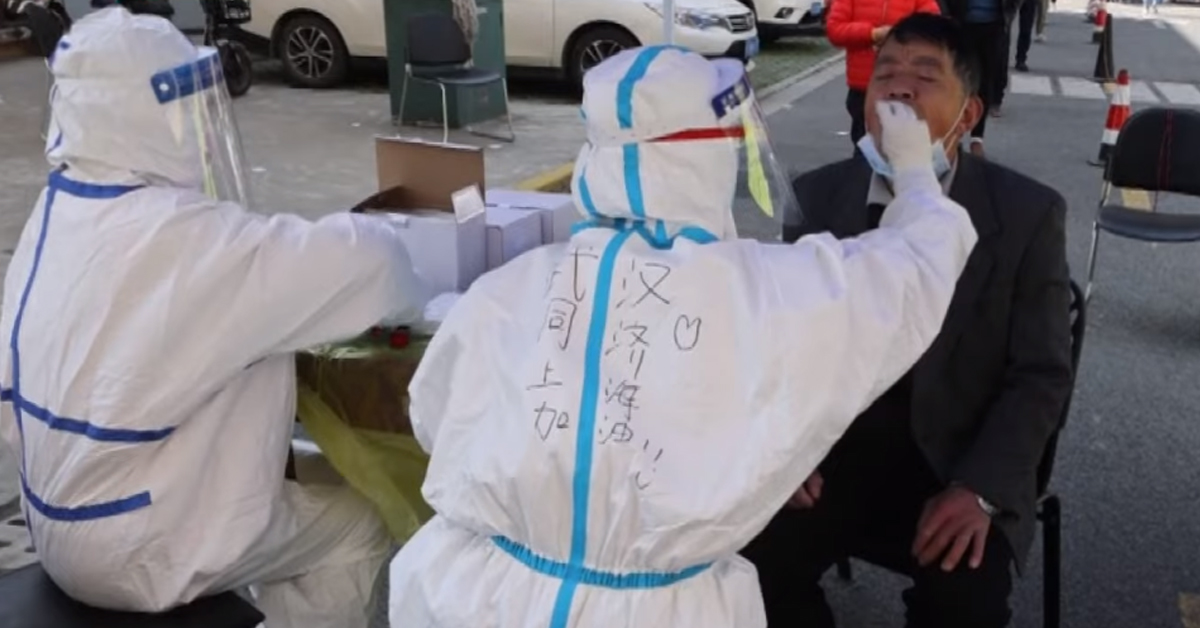

- As the zero-tolerance policy on Covid aggravates the slowdown, interlocking systemic challenges are likely to bring into question structural drivers that have underpinned China’s rise over the past half-century.

- This comes at a sensitive political time, as Xi Jinping launches into his third term at the Party Congress to be held later this year, and as tensions rise with the United States and its allies. Given the strength of the existing structure, however, it is probable that any prospective changes to China’s economic outlook will be hobbled by political considerations as the Party seeks to further conserve its grip on power.

The economic growth which has been the dominant narrative of China since Deng Xiaoping launched his reform programme nearly half a century ago has always had a primary political motivation. It has been the key to the stability of the regime and the Communist Party’s claim to power, as hundreds of millions of workers were brought into the labour force and a sizeable middle class developed, not to mention the hundreds of billionaires added to the top of the enrichment pile. Growth bred public confidence in the system and the Party which directed it, and thus provided the political backing the leadership required.

Deng’s prime objective was to use the economy to re-establish China as a major world power and make the Communist Party its unquestioned ruling force after the disasters of the Mao Zedong era. In return for improvements in their material condition, the citizens of the People’s Republic would be required to accede unquestioningly to the Party’s authoritarian rule; the consequences of not doing so made all too plain with the bloody crackdown on the protest movement of 1989, and the continuing suppression of anything regarded by the CCP as amounting to dissent.

When expansion faltered, as in 2008 and periodically thereafter, the political leadership moved in with stimulus packages designed to maintain the political status quo, enabling it to insist that the Communist Party must be supported in all it did as the only force able to steer China to national greatness. As the middle class expanded at the end of the 20th century, the CCP co-opted it with the basic regime bargain. Confounding those in the West who thought that it would seek democracy, the new class looked, rather, to its own interests and lined up behind the status quo which benefited it so nicely in material terms.

All the while, the connections grew stronger between the political power exercised by the CCP and the economy, with the flourishing of vested interests linked to the ruling establishment, from the “Princeling” relatives of high-placed officials down to local governments embedded in provincial business.

But now, serious strains stemming from the economy are showing themselves in the China Model, with its reliance on high debt levels and its pervasive imbalances. Their repercussions are set to face Xi Jinping with his most serious tests as he goes into his third term in power at the 20th Party Congress later this year, the central role of the economy making it the leadership’s greatest long-term cause for concern.

The malaise China faces runs deeper and reaches wider than the pandemic

The latest meeting of the Communist Party’s Politburo at the end of July was striking for what was missing from its public statement – any mention of the growth target set by the government for this year. Striking, but not so surprising since officials are reported to have been told that the 5.5% figure for the year set in the spring should be regarded as “guidance” rather than a hard objective. This was only a sensible recognition of reality. Year-on-year growth in the second quarter was put at only 0.4% and Prime Minister Li Keqiang warned that the foundations for recovery were “still unstable” while consumption continues to be hard hit; independent analysts have been forecasting for some time that the economy would be lucky to expand at as much as 4% for the year as a whole. And the final number now looks as though it may be in the region of 3% (See George Magnus’s February blog on China’s Weakening Expectations).

The particularly bad summer numbers may be attributed to the immediate impact of the draconian zero-tolerance policy on Covid, which has closed down cities across the country, disrupted supply chains and frozen consumer spending this year. Xi’s statement that, rather than harming the lives and health of the people, “it is better to temporarily affect economic development a little” is proving to be a considerable understatement as the BA.5 variant spreads and lockdowns of various kinds continue to hit around 200 million people.

The strains caused by the insistence on maintaining a policy that has taken such a toll was not lost on the Politburo which recognized the “war weariness” cadres might feel, but urged them to battle on while underlining the need to “look at the relationship between virus prevention and economic growth comprehensively, systematically, over the longer term, and especially from a political point of view”.

But the malaise China faces runs deeper and reaches wider than the pandemic. As the Party prepares for its Congress, the key question is whether the growth model that changed the world after Deng’s reforms began in the late 1970s is still viable, nearly ten years after then Prime Minister Wen Jiabao warned that the economy had become “unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable”.

Debt levels have increased despite official recognition of the danger they represent, and are likely to rise further under new stimulus measures. Consumption remains too low as a proportion of GDP, and fixed asset investment too high. Productivity has fallen. The huge property market is in crisis with the giant Evergrande firm defaulting, overall sales down by a third or more and limited but significant mortgage boycotts by buyers of uncompleted residences in around 100 cities. Financial pressures are mounting for local governments. Doubts have risen about some parts of the banking sector, particularly smaller institutions. The habitual recipe of applying stimulus through infrastructure brings diminishing returns. Unemployment is rising, particularly among young and migrant workers. Despite exhortations meant to encourage larger families, the demographic decline looks inexorable.

The combined effect of all this threatens to raise a deep and broad political challenge for the Communist Party, and its claim to lead on every front. A sluggish economy is not what the country is used to, or expects, from the Party. The “Common Prosperity” mantra adopted by Xi Jinping in an attempt to correct the imbalances of the Dengist China Model is at best a broad-brush approach which, as yet, offers no remedies commensurate with the scale of the problems the country faces.

The leadership’s insistence that “houses are for living in, not speculation” is hardly going to assuage the middle class which, on the back of steadily rising prices, bought heavily into real estate in the absence of other investment opportunities. Nor are private sector entrepreneurs, the main generators of growth, jobs and technological advance, likely to be enthused by the expansion of Party-State control which has become a hallmark of the current leadership.

Under Xi, the last ten years have seen repeated anti-corruption campaigns and the proclamation of ideological themes designed to strengthen the Communist Party and the national security state it dominates. Though the CCP has taken an increasing role in driving economic policy, these policies were primarily driven by politics and ideology to increase the grip of the Party State and build up “self-reliance” to free the PRC from dependence on overseas suppliers, particularly the United States.

This process could continue while growth remained strong, with the Trump administration’s sanctions turning out to be limited in impact and with China then benefitting from strong exports in the initial pandemic period. But now, the growth element that is so essential for the political power structure is diminishing, and, with it, there is a rising risk that public confidence in the regime will drop – though the current Taiwan crisis and prolonged confrontation with the United States may, coincidentally, rally support for the regime.

The transition to a better balanced, more sustainable economy would mean modifying or eliminating structural political props which have been central to the way the CCP operates

The political-social equation that was fed by economic expansion risks being upended as slowing growth, the real estate crunch, rising unemployment and the constraining impact of the Zero-Covid policy puts the relationship between the CCP and China’s citizens under strain. That threatens the stability which the CCP values so highly. It means that resolving the economic problems which lie behind the growth decline is likely to become the over-riding political concern of Xi’s third term.

But the transition to a better balanced, more sustainable economy would mean modifying or eliminating structural political props which have been central to the way the CCP operates, all the way from local governments to top-level decisions. With his mantra of Party Strengthening and the national security state, shielded behind rising nationalism over Taiwan and the US, there must be doubts as to whether this is the way Xi is willing – or able – to go.

If Xi does not accept the need to re-evaluate the China Model and accept the political consequences, the outlook is for China to be ever more subject to the requirements of the CCP, and to have its economic potential hobbled by the Party that, according to its repeated mantra, must lead in every domain.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the China Foresight Forum, LSE IDEAS, nor The London School of Economics and Political Science.

The blog image, “Draining“, is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Excellent summary and analysis of the challenging situation in China