Countries are borrowing heavily to keep their economies going during the pandemic. But emerging markets like those in Eurasia are struggling to fund stimulus packages due to capital outflows and the drop in oil prices. Armen Nurbekyan, Gevorg Minasyan and Tatul Hayruni (Central Bank of Armenia) make the case for the international community to augment IMF resources.

COVID-19 spares no country, regardless of its level of development. But emerging markets are in an especially precarious position, given that international investors are increasingly risk-averse. Indeed, capital outflows from emergency markets during the current market turmoil have put even post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) outflows in the shade – roughly US$98bn had flowed out of selected emerging markets by 22 April, according to the Institute of International Finance’s estimate, which is four times the GFC level. According to the World Bank, remittance flows to low and middle-income countries will plummet by US$100bn in 2020, a 20% decline. The fact these countries depend more heavily on tourism and commodity exports does not help either.

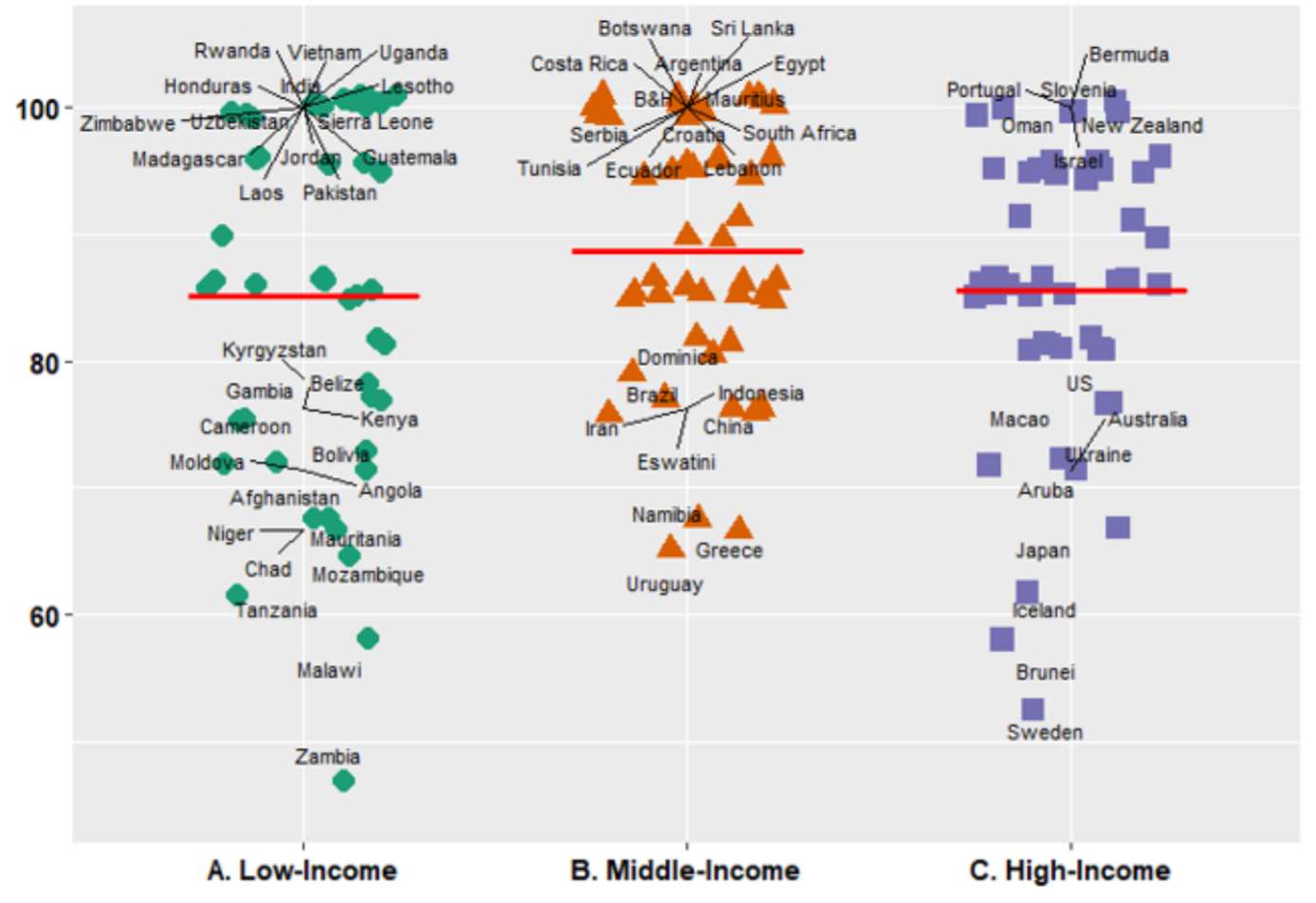

Despite their limited resources, emerging markets have imposed draconian measures to control the spread of the virus. The Stringency Index developed by the University of Oxford, which shows how strictly governments have responded, shows a similar pattern in high- and low-income countries (Figure 1). The shock will also be comparable. The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) World Economic Outlook for April marked down the 2020 growth rate for advanced economies by 7.7 percentage points (to -6.1%). Emerging markets and developing countries are revised down by 5.4 percentage points (to -1.0%).

Figure 1: Government Response Stringency Index (higher values indicate stricter measures)

Source: The World Bank, University of Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker and authors’ calculations.

Note: The classification of countries by the level of development is based on 2018 PPP per capita GDP (2011=100) levels. Income groups correspond to respective quantiles.

Most advanced countries reacted swiftly, announcing sizeable fiscal packages. But can developing countries afford to follow suit?

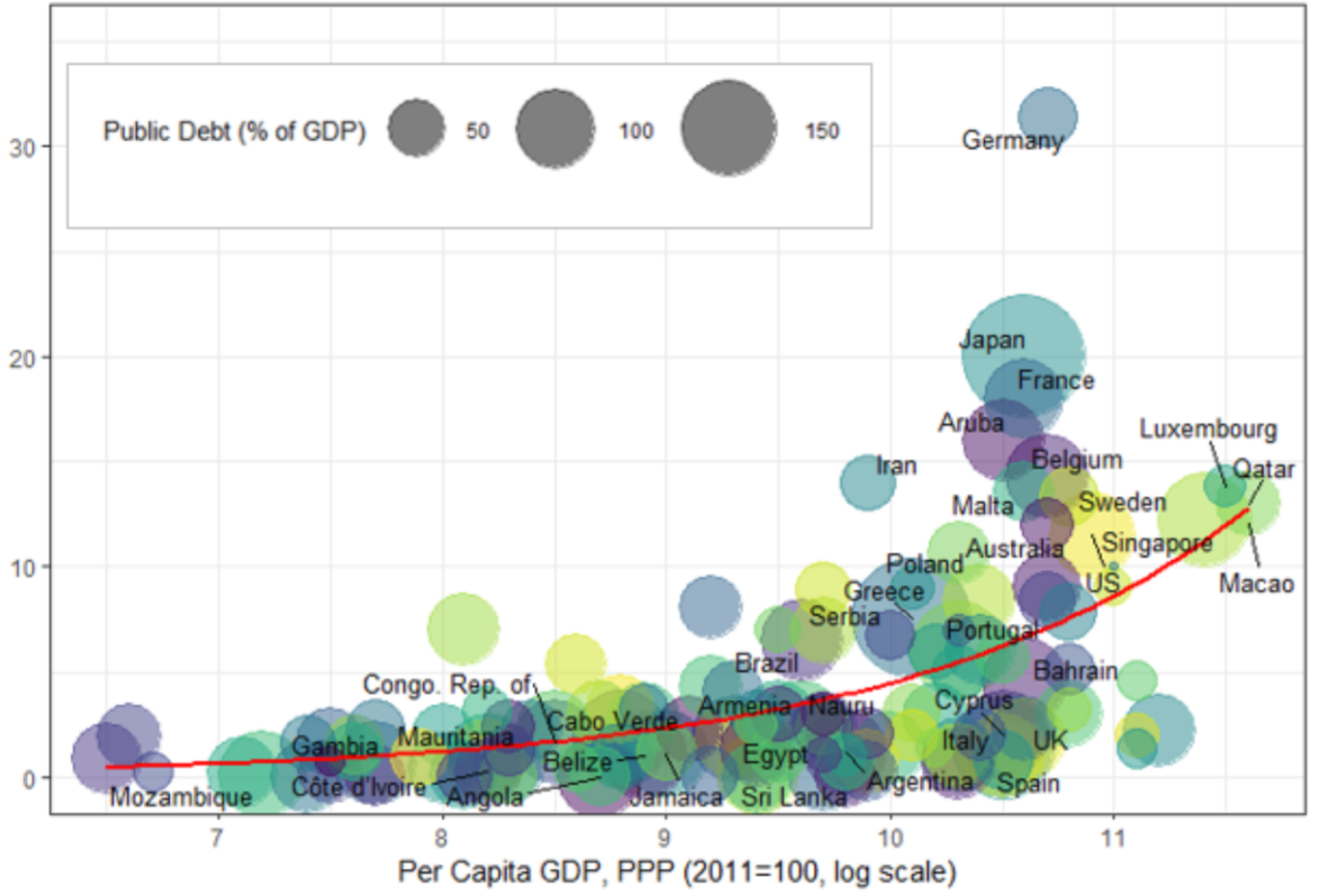

The preliminary answer is no. The size of fiscal stimulus packages clearly increases with income level (Figure 2). Moreover, the relationship is non-linear, indicating that the richest nations are far ahead of the rest.

Figure 2: Announced fiscal stimulus and income (% of GDP)

Sources: The World Bank, IMF Global Debt Database, IMF Coronavirus Government Response Tracker and authors’ calculations

The average size of fiscal packages in the lowest third quantile of countries by income is 1.4% of GDP. For the second quantile of countries, the mean size of fiscal stimulus stands at 3.2% —more than twice as high. For the richest group of countries it is 7.5%. Of course, these averages hide a great deal of variation, but the pattern is difficult to ignore.

Resource constraint is only one of many reasons for this: poorer countries, for example, may have implementation problems, as their capacity is lower. But do the ability to borrow – and the tight international financial markets – matter?

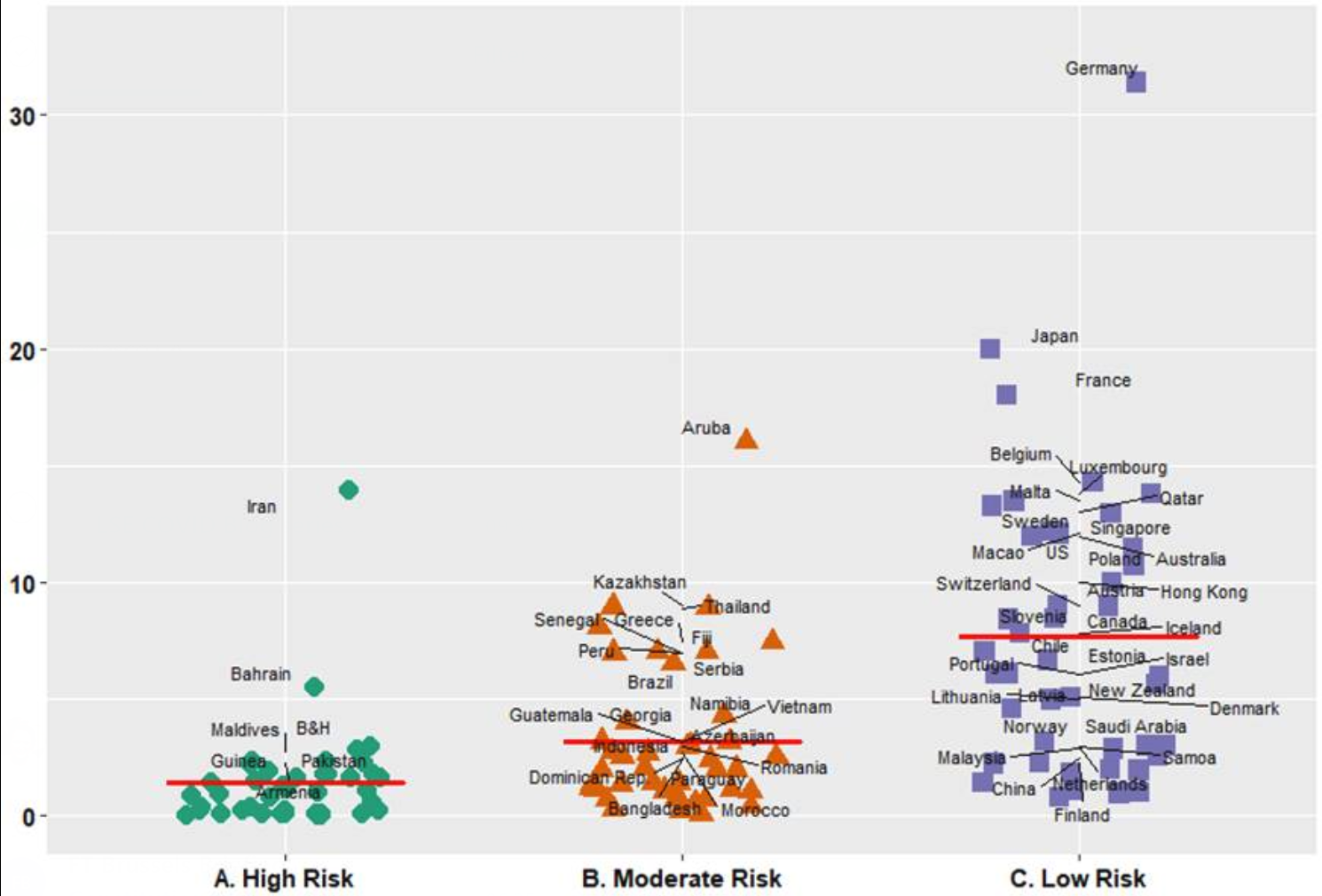

They do. Grouping countries by risk level (based on the average of rating agencies’ assessments) and comparing the stimuli packages shows that the size of the packages decreases with the size of the risk (Figure 3). A more formal regression analysis for a sample of 127 countries is also revealing. The level of per capita income does play a role, but that effect vanishes when credit ratings are included in the regression (Table 1). This suggests that the capacity to borrow significantly affects decisions about economic support.

Figure 3: Announced fiscal stimulus and risk (% of GDP)

Source: IMF Coronavirus Government Response Tracker, Trade Economics (TE) and authors’ calculations

Note: The methodology of TE was used to convert agency ratings into a numeric scale between 100 (riskless) and 0 (likely to default).

A closer look at the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), of which Armenia is a member, vividly illustrates the general point. The EEU consists of oil and gas exporters (Kazakhstan and Russia) as well as oil importers (Armenia, Belarus and Kyrgyzstan). The 65% drop in oil prices since the COVID-19 outbreak added greatly to economic stress in oil-exporting countries. The IMF now expects the Russian economy, the largest in the union, to contract by 5.5% in 2020, compared to 1.9% growth forecast last October. Oil importers are expected to benefit somewhat from lower oil prices. But, as the 2015 oil price shock illustrated, the negative spillovers through trade and remittances from Russia will significantly outweigh the gains.

Table 1: Regression results of fiscal stimulus

| (1) fis_stimul | (2) fis_stimul | |

|---|---|---|

| 1n_gdp_ppp | 2.209*** (0.316) | 1.202* (0.473) |

| sov_debt_rat | 0.0618** (0.0221) |

|

| _cons | -16.80*** (3.018) | -10.61** (3.677) |

| N adj. R-sq | 127 0.75 | 127 0.313 |

| Standard errors in parentheses * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 |

Source: Authors’ estimates

Note: fis_stimul – fiscal stimulus (% of GDP); ln_gdp_ppp – PPP per capita GDP (2011=100) in log scale; sov_debt_rat – numerical score of sovereign debt credit ratings.

The drop in oil prices resulted in significant exchange rate depreciation – the US$ nominal exchange rate depreciated on average by about 10% in the EEU. Monetary policy had very limited ability to respond. Armenia reacted swiftly and was the only country able to cut the policy rate until 24 April; Kazakhstan initially raised the rates by 2.75 percentage points, but later reduced it again by 2.5 percentage points. Russia cut interest rates by 0.5 percentage points on 24 April. The average fiscal stimulus will amount to around 2.5% of GDP. The case of Georgia is similar in many respects.

The IMF was among the first to provide emergency financing. Kyrgyzstan, for example, secured US$120.8m through the IMF’s Rapid Financing Instrument (US$80.6m) and Rapid Credit Facility (US$40.3m), amounting to 1.5% of GDP. Armenia reached a preliminary agreement to extend its existing US$240m standby arrangement by nearly US$180m (1.3% of GDP), of which US$280m will be available as soon as the IMF’s executive board makes the decision. IMF support to Georgia increased by about US$375m (2.4% of GDP) to help finance health and macroeconomic stabilisation measures. With the financing available to Georgia on completion of the review, total disbursements under the arrangement will amount to US$450m.

Table 2: Fiscal and monetary response in EEU countries and Georgia

| Fiscal stimulus (% of GDP) | Change of key policy rate (pp) | NER depreciation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EEU | |||

| Armenia | 2.3 | -0.50 | 0.2 |

| Belarus | 0.0 | 0.00 | 8.3 |

| Kazakhstan | 9.0 | 0.25 | 13.4 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 0.1 | 0.00 | 14.0 |

| Russia | 1.4 | -0.50 | 9.6 |

| Georgia | 4.0 | -0.50 | 15.1 |

| Average | 2.8 | -0.21 | 10.1 |

Sources: IMF Coronavirus Government Response Tracker, national central banks and authors’ calculations

Tight international financial markets mean emerging markets are finding it difficult to support their economies. The procyclicality of financial markets is, of course, not news, but the nature of this shock and the associated uncertainty is extraordinary. The packages announced by the governments of developing countries are limited by these tight constraints, and are paltry in comparison to those in advanced economies. Of course, it is hard to blame developing countries for somewhat muted responses — the possibility of several waves of the pandemic means they may do well to keep their powder dry.

A significant increase in public debt across the board after the end of the pandemic is, however, inevitable. Advanced countries historically dealt with this problem by using a combination of generating fiscal surpluses, as well as financial repression — essentially inflating away debt by keeping interest rates low. This is yet another respect in which emerging markets differ. Inflating the debt away is hardly an option, as most public debt in emerging markets is external and denominated in foreign currency.

Emerging markets will try to strike a delicate balance between fiscal prudence and decisive moves to pull people and business out of chaos. Yet the social consequences of this shock are unprecedented, and insufficient efforts to address them may result in tectonic shifts in the social contract, which is the last thing governments need during a pandemic. Governments should act confidently, as the confidence effects of their actions during times of uncertainty are sizeable. To quote Zig Ziglar, “confidence is going after Moby Dick in a rowboat and taking the tartar sauce with you”.

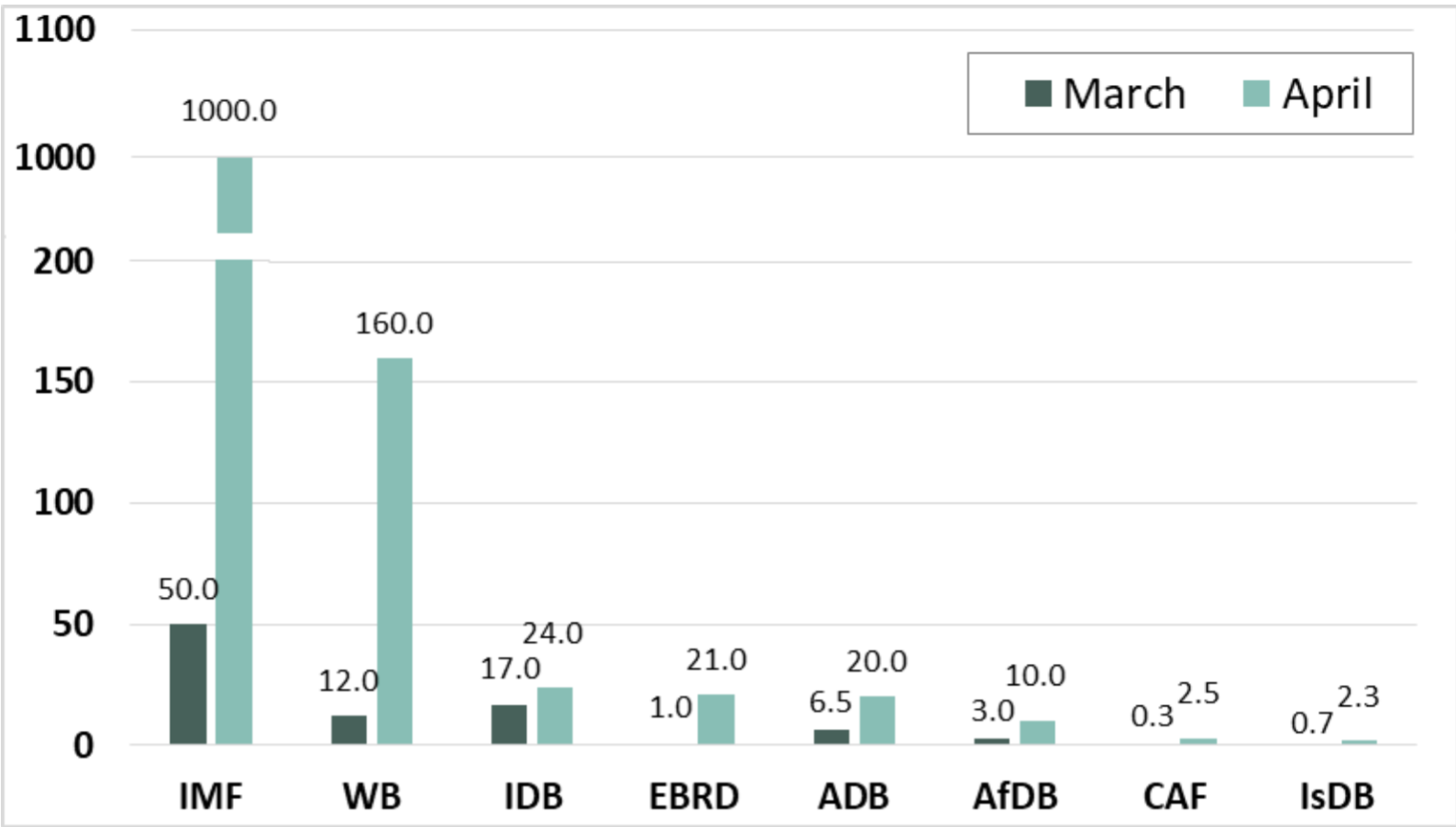

The IMF with its US$1trln firepower is by far the best institution suited to help developing countries and was the quickest to respond (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Available resources of international organisations (US$bn)

Sources: Announcements from international organisations and authors’ calculations

The international community must back up the IMF and increase its resources: international organisations like the IMF hold the key to ensuring that developing countries are able to withstand the shock. If not now, when?

The authors would like to thank Martin Galstyan, Vahagn Grigoryan and Nerses Yeritsyan for valuable discussions which helped to write this note. Piroska Nagy Mohacsi was instrumental in focusing and shaping the note. Ros Taylor’s valuable edits significantly improved this post.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE, nor the Central Bank of Armenia.

1 Comments