What are the challenges faced by urban transport of the densely populated metropoles of the Global South in the face of COVID-19? In this blog, John T. Sidel (LSE) discusses the case of the Philippines.

As politicians and policy wonks here in the UK have begun to discuss and debate the phased loosening of the lockdown imposed on the country on March 23rd, a chorus of questions and concerns has been voiced in response to the challenges and constraints presented by the urban transport system on ‘social distancing’, especially in London. BBC reporters have mused about the possible need to deploy police officers to restrict and restrain commuters flowing back into the Underground stations of the capital. The leaders of three unions representing railway workers have written to Prime Minister Boris Johnson warning that an increase in train service would put the lives of passengers and rail staff at risk. Recently televised footage of crowded buses and trains has increased concerns about the dangers of COVID-19 transmission through the resurgence of passenger traffic on public transport.

As the CEO of Heathrow Airport, John Holland-Kaye, admitted in a recent interview with Bloomberg TV, “social distancing just cannot work in any transportation system.” Indeed, dozens of London bus drivers fell victim to the virus due to their fatally close contact with passengers, even under the original lockdown restrictions on mobility. Meanwhile in New York City, the continuing operations of the subway – even at only 10% of its usual level of passenger traffic – has cost the lives of more than one hundred Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) workers since the outbreak of the pandemic.

If concerns about reorganizing urban transport to meet the challenges of COVID-19 in such wealthy cities as London and New York are so serious, what about the densely populated metropoles of the Global South? In cities across Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East, urban transport systems were already under considerable strain before the onset of the global pandemic. With public investment in urban transport infrastructure failing to keep up with demographic and economic growth over recent decades, millions of urban and suburban residents and workers have been shouldering higher and higher costs – in money, time, and health – for their daily commutes with every passing year. With a privileged minority clogging the roads in their private air-conditioned cars, the majority of commuters in such cities have been paying heavily for ‘motorization’ and for the cartel-like arrangements and petty corruption which prevail in the urban public transport sector.

By early 2020, everyday life in many cities across the Global South involved long queues at stations and terminals, overcrowded trains, buses, minibuses, vans, jeeps, and other public utility vehicles, and interminable traffic jams. Against this backdrop, the dangers of persistent transport gridlock necessitated the harsh forms of lockdown or quarantine imposed across many countries of Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East over March and April of this year. Thus the question arises: if the weeks and months ahead will see the relaxation of restrictions on movement in country after country, how can urban transport systems in the Global South be reorganized and reformed to prevent them from serving as dangerously effective incubators and transmission belts for a second wave of the coronavirus?

Here the case of Metro Manila, the national capital region of the Philippines, is instructive, given both the scale of the problems with the city’s transportation system and the active efforts of urban transport reform advocates to present creative solutions. On the one hand, as of early 2020, intensifying congestion had landed Metro Manila second-worst ranking in a global survey of traffic conditions in 416 cities across 57 countries and generated estimates of costs to the Philippine economy estimated at no less than PHP3.5 billion (US$67 million) per day. With automobile and motorcycle sales putting hundreds of thousands of new private vehicles on the roads every year over the past decade, and sustained demographic and economic growth leading to intensified urban and suburban sprawl over the same period, so-called ‘carmageddon’ was inevitable.

Meanwhile, Metro Manila’s extremely limited over-ground rail transit system has grown at a snail’s pace and suffered from recurring interruptions to its service. Thus urban and suburban commuters have remained reliant on overworked, underpaid bus, minibus, van, and jeepney drivers competing for kerbside for passengers – to pay the ‘boundary’ (daily rent) to risk-averse, well-heeled, and often politically connected vehicle-owners – and roadside for space amidst an ever thicker flood of cars and motorcycles, thus leading to gridlock, a man-made – and market-made – economic, environmental, and social disaster.

On the other hand, by early 2020, worsening traffic congestion had combined with the accumulated anger, intellectual energies, and organizing abilities of Metro Manila commuters to give rise to an increasingly vibrant network of urban transport reform advocates and activists enjoying a growing audience of supporters via social media and the b/vlogosphere. Established urban transport gurus like Dr Robie Siy have been joined by a younger generation of urban planners and transportation specialists in the formation of an interlocking directorate of transport reform advocacy groups, like Alt Mobility PH, the Inclusive Mobility Network, Komyut, Sakay.ph, and Move Metro Manila. With support from overseas development agencies like The Asia Foundation, these groups have engaged in diverse forms of reform advocacy, ranging from lobbying in both houses of Congress and in the Department Of Transportation (DOTr) to regular newspaper, radio, and television interviews, social media postings, petitions, surveys, and videos.

Over the course of the past few years, these urban transport reform advocates have developed a clear consensus on a holistic blueprint for the reorganization of Metro Manila’s transportation system to induce traffic decongestion and improve the quality of life of the residents, workers, and commuters in and around the national capital. The blueprint involves not only support for the DOTr’s official plan for expanded overground and new underground rail transit across Metro Manila, but also the introduction of a new Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system along the lines of the successful experiments undertaken in Seoul, Korea as well as a number of cities in South America. The blueprint also includes enhanced regulation of bus, minibus, and jeepney routes and a shift to a system of hourly wages and thus rationalized incentives for public utility vehicle drivers. Finally, the blueprint extends to the realm of ‘micro-mobility’, with provision of bicycle lanes and pedestrian walkways for the ‘first and last miles’ of urban and suburban commutes. The overall thrust of the blueprint is to promote mobility of people – rather than vehicles – by shifting traffic from private automobiles into a more organized, efficient, equitable, and eco-friendly public transport system.

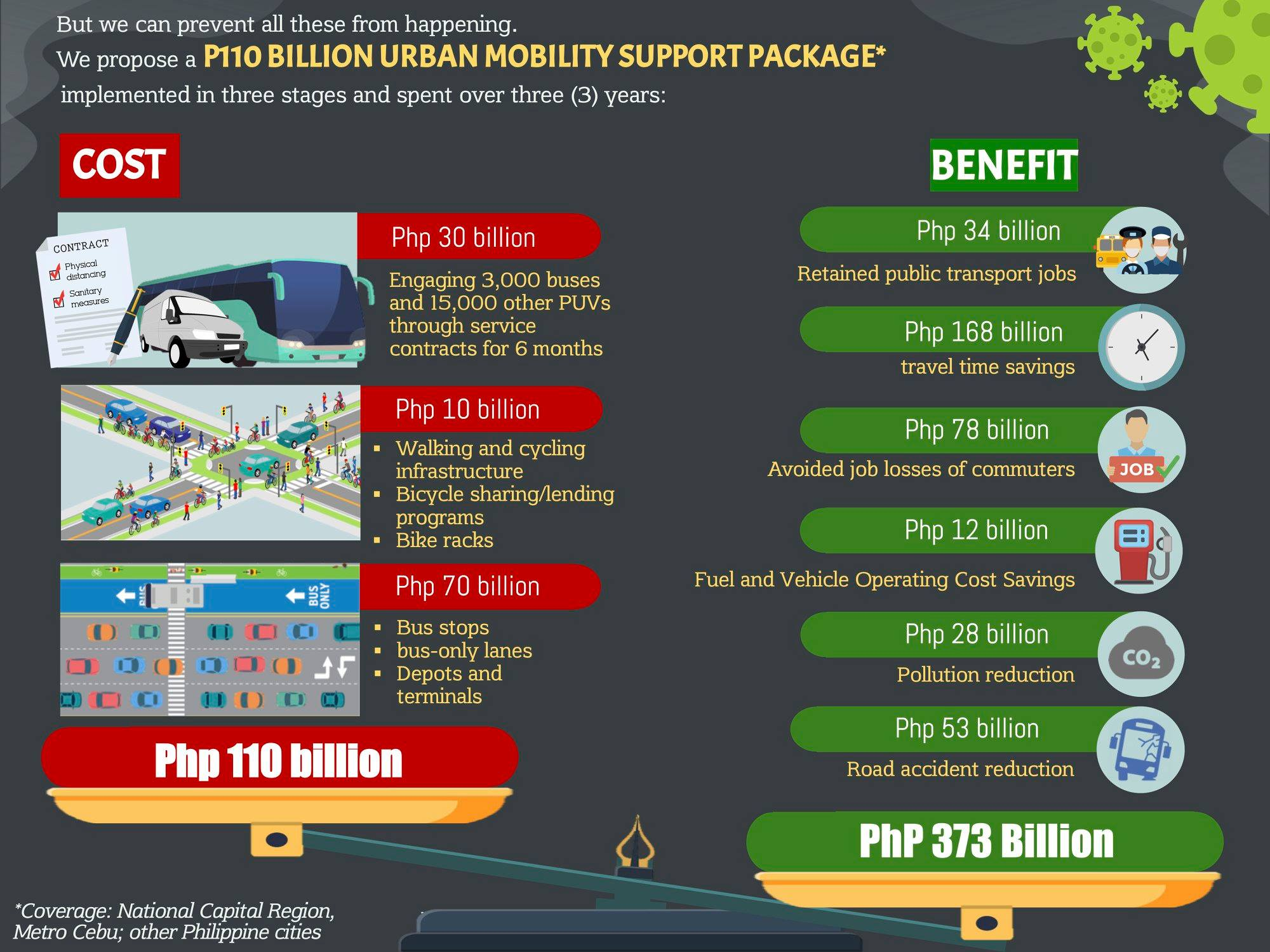

Since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis in the Philippines, these urban transport reform advocates have shifted into high gear, producing an equally coherent and compelling blueprint for the reorganization of Metro Manila’s transportation system in the context of the crisis, with the short-term imperative of protecting public health through ‘social distancing’ consistent with the longer-term imperative of promoting mobility through systemic reform. Through the newly formed #MoveAsOne Coalition, this blueprint has been presented to leading DOTr officials, key legislators in both houses of Congress, and other key policy-makers and the public at large.

With the May 16th shift from the Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) to a less stringent Modified Enhanced Community Quarantine (MECQ), hundreds of thousands of workers have begun to move around Metro Manila, along additional hundreds of thousands of residents engaged in travel to obtain medicine, medical care, and other necessities, thus a resumption of large-scale flows of movement across the national capital region every day. To cope with this sudden resurgence of traffic, urban transport reform advocates affiliated with the #MoveAsOne Coalition are recommending a set of measures to reduce the dangers of a second wave of the Coronavirus transmitted via the national capital region’s transportation system.

Some of the recommended precautionary measures are self-evidently sensible and straightforward. Rail, bus, and other public transport vehicles should be operating at a maximum of 50% capacity, with passengers spaced out to maintain social distancing. Masks should be made mandatory for both passengers and drivers, temperature checks required prior to boarding, as well as impermeable barriers protecting drivers from infection by passengers and vice versa. Vehicles should be disinfected at least twice a day, with transport depots and offices likewise operating under equally strict procedures to maintain a high level of public hygiene. Similar measures are likewise recommended for the taxis, transportation network vehicle services (TNVS), and ‘tricycles’ providing the ‘first and last miles’ of daily commutes.

But the #MoveAsOne Coalition’s recommendations include a much more systemic reorganization of Metro Manila’s urban transportation system, in line with both the short-term exigencies of the pandemic and the longer-term imperatives of reducing traffic congestion in the national capital region once all restrictions on movement are lifted. Here the #MoveAsOne Coalition’s transport specialists are especially concerned about the difficulties of controlling the supply of public transport and constraining kerbside competition for passengers, the economic pressures on drivers to overload vehicles, and the risks of virus transmission accompanying the payment of fares in cash. In this context, the following major policy changes are recommended:

A shift of all road-based public transport in the national capital region to government-contracted vehicles operating as a public service, both on trunk routes contracted by the DOTr and feeder routes contracted by local governments; Free bus and jeepney rides until a cashless fare collection system is established; A network of ‘safe streets’ closed to vehicular traffic, sidewalks improved and widened for pedestrians, and protected bike lanes established for cyclists.

Such recommendations for government provision of investment and infrastructure for public transport across Metro Manila are fully in line with urban transport reform advocates’ holistic vision of a more efficient, equitable, and eco-friendly transportation system for the national capital region over the years ahead.

Unfortunately, a plethora of political obstacles stands in the way of the adoption of these recommendations by the Philippine government, at least the more ambitious – and costly – measures requiring public investment in Metro Manila’s transportation system. Here commentators often allude to the limited receptivity to such plans shown by DOTr Secretary Arthur Tugade, a stance usually attributed to his reported standoffishness and short-temperedness in the face of policy advice proffered from outside his own circle of personal advisors. But the underlying impediments to a reorganization of Metro Manila’s public transportation system are much more structural and systemic, and they remain stubbornly strong even in the face of the ongoing crisis.

On the one hand, the institutional arrangements and resources for government oversight of, and investment in, the national capital region’s transportation system are woefully inadequate for purposes of implementing systemic reform. The Department Of Transportation (DOTr) itself has a very limited plantilla and little in the way of institutional memory or capacity, with a pronounced reliance on short-term contractors and consultants. The DOTr, moreover, shares authority over Metro Manila’s transportation system with a set of ancillary or attached agencies, many of whose heads enjoy both formal prerogatives and personal/political linkages which undermine effective oversight by the DOTr Secretary. The Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB), for example, is run by a long-time close associate of President Duterte from their hometown of Davao City, while the separate Land Transportation Office (LTO) is overseen by a former Director-General of the Philippine National Police (PNP), and the Light Rail Transit Authority (LRTA) is led by a former PNP Intelligence chief who was once convicted for his role in a series of kidnappings in the 1990s. At the same time, the seventeen elected mayors of the constituent cities (and one municipality) of Metro Manila – and the Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA) – are involved in traffic enforcement and other forms of transport regulation that overlaps and conflicts with the powers and prerogatives of the DOTr and its agencies.

On the other hand, the private business interests controlling the commanding heights of Metro Manila’s transportation system are pitted against the agenda for holistic reform. A small cluster of diversified conglomerates have vested interests in the automobile sales (and private toll roads) which have flooded the thoroughfares of the national capital region with private cars, and they likewise control the slow, selective expansion of the limited rail system in line with their real-estate and retail interests across the metropolis and its hinterlands. A larger and looser cartel of bus companies remains concerned to protect its lucrative franchises and to preserve a ‘boundary’ system that leaves financial – and now physical – risks with bus drivers and ticket collectors, while ensuring a steady daily ‘rent’ for their fleets of vehicles. These private interests are heavily invested in the status quo – and well represented within the agencies of the national government, Congress, and in city halls across Metro Manila – and ill-disposed towards holistic urban transport reform.

Overall, the challenges of reorganizing urban transportation systems in densely populated cities of the Global South like Metro Manila are not only technical but also political. The problems of intensifying urban traffic congestion in cities like Metro Manila in the years preceding the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic came as a result of government policies which have systematically favoured private automobiles and a privileged set of interests organized around automobile production, sale, and ownership over the greater good represented by public transportation via integrated bus and rail systems and various forms of non-vehicular micro-mobility. The overcrowding of buses, minibuses, vans, jeepneys, and other such public utility vehicles has reflected these conditions as well as the microeconomic incentives imposed by cartelization and corruption on overworked and underpaid drivers and fare collectors. These underlying pre-conditions now threaten to enable the transmission of a second wave of the virus among millions of ordinary commuters through circuitries of urban transportation systems dangerously clogged up by the privileged – and protected – few ‘social distancing’ on the roads in their private automobiles. Thus transport reform advocates in cities across Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East merit strong support from local constituencies, government leaders, as well as overseas development agencies and international financial institutions, as they push for the implementation of innovative solutions not only to the COVID-19 crisis but to more longstanding and deeply rooted problems with urban transportation systems across the Global South.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog or LSE.