Keeping people in work has been a policy priority since the COVID-19 pandemic began, because full economic recovery is not possible without consumer demand. Companies are adapting to the new circumstances, but job creation is lagging behind. Paula Kukołowicz (Polish Economic Institute) looks at the reasons why.

With a second wave of infections apparently underway, the outlook for European economies looks decidedly uncertain. The European Commission predicts that recovery in aggregate output will still be incomplete by the end of 2021. One reason is the slowdown in private consumption, which has traditionally been considered the backbone of economic growth. However, the recovery in the employment rate seems to be even more uncertain. During the economic recessions in the 1990s and 2000s in the United States and the European Union, the unemployment rate continued to increase even when aggregate output rebounded, questioning the long-established positive relationship (known as Okun’s law) between economic growth and unemployment reduction. Might this time be different?

The coronavirus crisis has significantly affected the way businesses operate. Some sectors of the economy – predominantly entertainment and recreation, accommodation and transport – might undergo structural changes. While evidence at the level of individual companies is still scarce, a recent report by the Polish Economic Institute demonstrates that they are becoming risk-averse. While quarantine measures were being lifted, the numbers of new hires lagged behind their current market performance, while their planned layoffs were largely unrelated to rising revenues. This may have profound implications for both the labour market and the economy more widely.

The PEI carried out six business surveys in Poland between early April and early July 2020, using a sample of 400 firms in each wave. The first three waves of the survey were performed while quarantine measures were gradually introduced from mid-March to early April 2020, while the fourth and fifth waves were conducted as they were being eased, between mid-April and late May. The final wave, in early July, captured the situation when the vast majority of the restrictions had been lifted.

The economic lockdown severely affected the overall performance of Polish economy. Industrial production plunged in April by -23.7% compared to February, while retail sales fell by -15.2%. In mid-April 61% of the companies surveyed had registered a fall in sales compared to the previous month.

Poland adopted various forms of work preservation scheme. These included stoppage benefits paid to the self-employed and workers on civil contracts, childcare benefits provided to parents who were not able to work due to (pre)school closures, and co-financing of employees’ salaries for companies who experienced problems due to the crisis. The latter solution allowed firms to either temporarily lower the number of hours worked by employees or introduce economic lockdown, under which employees were not obliged to work. In both cases, the state subsidizes employees’ salaries for a period of three months, on the condition that no job cuts are made.

These programmes were largely effective. In the second quarter of 2020 the number of people employed in Poland dropped by -1.2%, which is better than the EU average (-2.9%). This moderate fall in employment was accompanied by a significant rise in the share of people employed, but temporarily not working. In the second quarter of 2020 over 1.2 million employed workers stayed out of work, of whom over 600,000 did not work because of their employer lockdown.

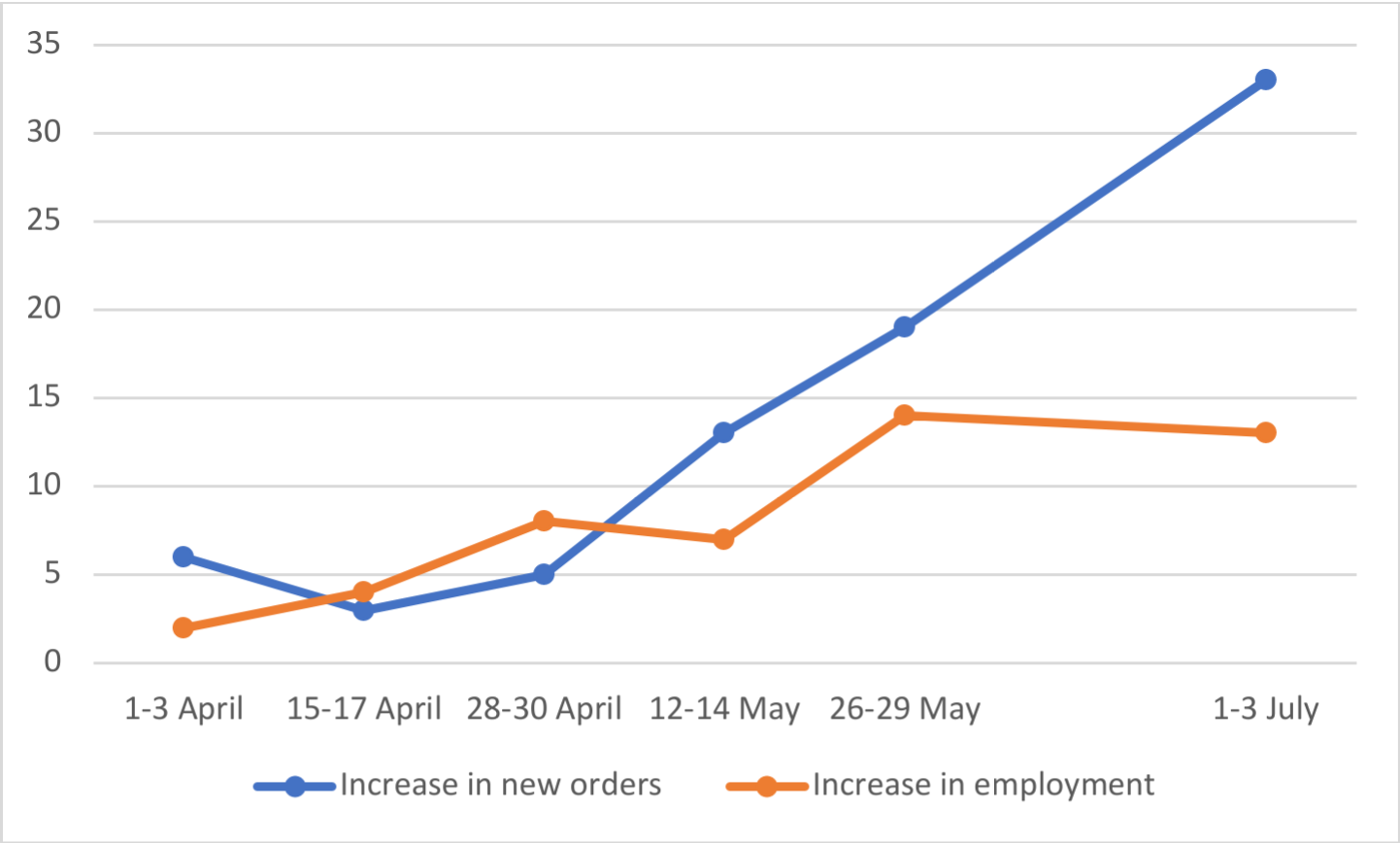

However, these layoffs may be difficult to reverse. Polish business surveys suggest that companies have become risk-averse. Overall, 12% of businesses surveyed declared they had cut their workforce in late March and April as a result of the coronavirus crisis. The gradual rise in sales that was observed from the end of April, when the process of unfreezing the economy had already begun, was scarcely accompanied by plans to recruit new workers (Fig.1). The percentage of companies with a rising number of new orders jumped from 5% in late April to 19% in late May and to 33% in early July. At the same time, the rise in the percentage of firms planning new hires rose from 8% to only 13%, just at the margin of statistical error.

Figure 1: The dynamics of businesses’ new orders and plans to recruit new workers

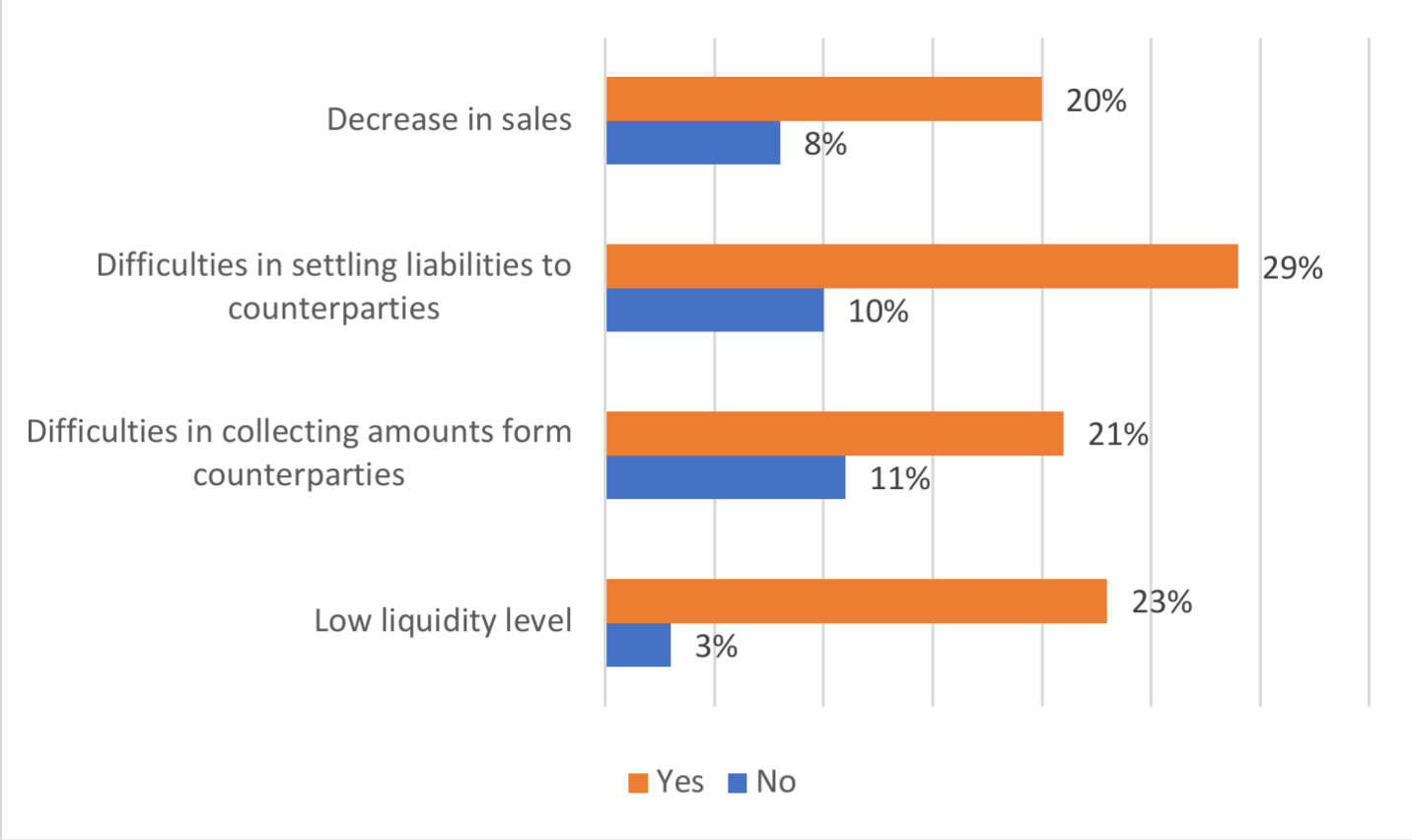

The conclusion that the expected economic recovery might not lead to commensurate growth in jobs seems even more obvious when we examine the factors that make companies cut their workforce. Firms with declining sales, those facing payment backlogs or who were experiencing liquidity problems more often declared that they were planning layoffs than those that faced no such difficulties. While the percentage of firms planning job cuts ranged from 3% to 11% among companies in a favourable market situation or adequate access to liquidity, it was much higher among companies with decreasing sales (20%), problems with settling their liabilities to business partners (29%), difficulties in collecting payments owed to them (21%) or those with inadequate access to liquidity (23%) – as depicted in Panel A of Figure 2.

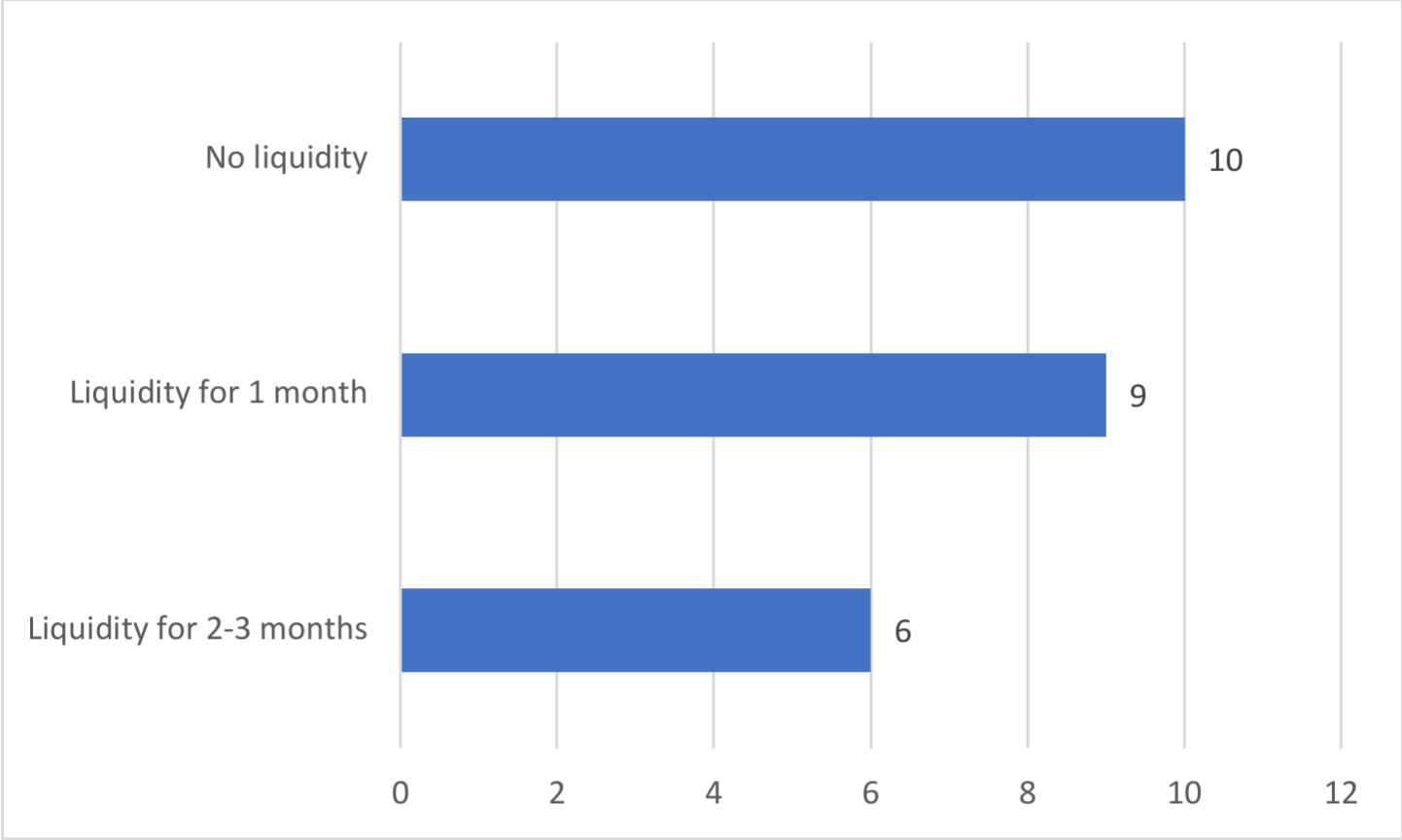

So we might conclude that companies facing problems turn to job cuts as a solution. This seems unsurprising. However, a radically different picture emerges when the influence of all these factors is evaluated simultaneously in a single multivariate regression model. This model takes into account the fact that liquidity levels, payment backlogs and current sales are mutually correlated and so their relationship with firms’ staffing strategies should be considered jointly. Taking this possibility into account reveals that the only factor significantly related to planned job cuts is access to liquidity. Companies who have it are less likely to carry out layoffs than those with low liquidity levels, regardless of their current sales and payment backlogs. Companies with access to liquidity for 2-3 months are 6 percentage points more likely to reduce employment than companies with liquidity for over three months. The difference approaches 10 percentage points when companies with no liquidity are taken into account. At the same time, the other factors – current sales and payment backlogs – when assessed alongside liquidity levels turn out to be unimportant.

Figure 2. Propensity to reduce employment: the effect of market situation and access to liquidity

Panel A. Raw averages for respective groups

Panel B. Differences in predicted probabilities of reducing employment: comparison to a scenario of access to liquidity for more than three months (in percentage points)

Note: Results based on logistic regression estimates

Overall, the survey data suggests that the expected economic recovery might not translate to full or swift restoration of jobs. It suggests that uncertainty about future sales is informing companies’ decisions. At the same time, the default model of firms’ structural adaptation hinges upon attempts to cut personnel costs.

So what are the implications for European economies? Decision makers – at least in some countries – might be tempted to think that their countries have evaded the risk of significant labour market disruptions. According to Eurostat data, the unemployment rate in many European economies has barely changed. However, British labour force surveys suggest that this optimism might be misguided. They show that behind the stable unemployment rate is a rising number of people without work and not looking for a job. They run the risk of falling into permanent economic inactivity. From this perspective, it seems that the aid programmes adopted by many European governments were rightly focused on preserving jobs rather than the direct restoration of consumer demand. This stands in stark contrast with the way the crisis was handled in America. In particular, it remains to be seen whether the 30 million people who were made redundant in the early phase of the crisis will be able to return the labour market when the recession finally ends.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.