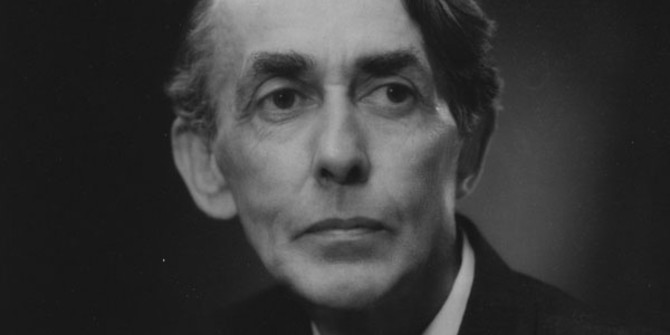

Tracking inequality is difficult, not least because we lack complete information about the distant past. Lucinda Platt (LSE) explains how the LSE social researcher Richard Titmuss challenged claims that the state had become too redistributive by measuring inequalities in new ways. As we begin to think about the ways in which COVID-19 has made society more unequal, we can learn from his approach.

Inequality has been a growing preoccupation in recent years, and especially so since the pandemic. But academics have been discussing it for a long time. The ways we think about and analyse inequality have been fundamentally influenced by critical work carried out some decades ago by, among others, Richard Titmuss.

Richard Titmuss has had an enduring effect on the way we think about inequality and its measurement. So it is a good moment to revisit his work on these topics and to identify the importance of his insights and careful analysis. In particular, his work on the income distribution – of inequality and the gap between those with higher incomes and those with less – addresses questions of how best to measure the distribution and estimation of income inequalities, and to what extent there has been redistribution to reduce underlying inequalities in employment and pay. The questions of how far things are becoming more or less unequal, and what the pattern of change has been in both the short and the long run, continue to be debated and new evidence is still being presented.

For example, Tony Atkinson and Stephen Jenkins published a recent paper, which traces income inequality back to 1937 – the year and the data that Titmuss used to examine the change in the pre-and post-war income distribution in his 1962 book, Income Distribution and Social Change (IDSC).

Recent attention has been paid to wealth holdings as opposed to income, and there is closer scrutiny of the relationship between the two. The nature of the relationship between income and wealth was, however, a key element of Titmuss’s discussion in IDSC, nearly 60 years ago. This careful attention to how we think about the different components of economic welfare in fact goes back to his influential 1955 essay on “The Social Division of Welfare”, in which he set out a number of the issues later addressed in IDSC.

In “The Social Division of Welfare”, Titmuss sets out the question of whether or not there has been redistribution from rich to poor. More specifically, he scrutinises the claims that the hard-working middle class – the taxpayers – have been impoverished for the benefit of those lifted out of indigence through the provision of ‘social welfare’. Such claims resonate clearly with statements heard today, which regularly distinguish ‘hard working families’ or ‘taxpayers’ from ‘benefit dependants’.

Titmuss focuses on what in fact comprises ‘welfare’, and the ways in which not only social services (such as family allowances, unemployment benefits, non-contributory pensions etc.), but also fiscal adjustments, such as tax allowances for dependants, and occupational benefits (meal vouchers, company cars, training grants, medical bills, children’s school fees) are all forms of ‘social services’ that recognise certain forms of dependency (such as the extended period children spend in education). He points out how all three domains of ‘welfare’ provide different forms of redistribution – or cost to the exchequer – that disproportionately benefits the better-off, the middle classes. In these insights, Titmuss foreshadows some of Julian Le Grand’s work on the beneficiaries of the welfare state, if a broader understanding of welfare beyond social security is used.

But Titmuss’s agenda in this essay was also to reflect on social change, and the mistake of trying to evaluate the present with reference to a past where life was so different in terms of life expectancy, time children spent in school or training, and in the specialisation of work.

This issue of incommensurability between past and present was central to his analysis in IDSC. He challenged the ‘received wisdom’ of the day that the welfare state had been ‘excessively’ redistributive, and did so by reference in large part to the fact that the world that was measured in 1937 tax data was radically different from that being evaluated in the post-war period.

His work with tax data foreshadowed subsequent work carried out also at LSE by Brian Abel-Smith and Peter Townsend, who used survey data collected in order to estimate living standards and inflation to evaluate the question of whether poverty had indeed been ‘abolished’ by the welfare state. Such claims had been put forward rather optimistically by, for example, Seebohm Rowntree in his third and final poverty survey of 1951, carried out with G R Lavers. Their work on these data, and Townsend’s subsequent poverty research, fundamentally shaped the measurement and understanding of poverty in the UK up to the present.

But unlike the work of Abel-Smith and Townsend, Titmuss’s aim in IDSC is not simply to correct the record. Certainly, that is an important part of the study, reflected in the ways he delves into the nitty-gritty of how to measure population numbers and tax units, especially as they evolve over time, the nature of the accounting period, and the tax status of inter vivos exchanges. But more important is his ambition to chart the nature of social changes, which are on such a scale, he argues, as to make comparison with the past not only well-nigh impossible but inherently meaningless. Such social changes include the processes of transfer of resources from income to capital and between family members by the better off, the benefits accruing to particular jobs with increasing specialisation in work, and the ways that work, family and ‘dependency’ have all undergone major transformation. The exercise of power, the consolidation of resources, the growing inequalities in wealth even if not in income, increasingly regressive principles dominating taxation, the role of the educational system in shaping life chances – and perpetuating inequalities – all these are the targets of Titmuss’s analysis. Strikingly, they remain central to contemporary analysis and concerns.

“Ancient inequalities have assumed new and more subtle forms”, concluded Titmuss. Despite his warnings that we should not expect continuities with a distant past, his targets of analysis and his focus on accurate measurement remain salient for considering today’s subtle forms of inequality. We continue to have much to learn from his insights and approach.

Lucinda Platt, Julien Le Grand, Jon Ashworth, Sara Machado and John Stewart discussed Richard Titmuss’ legacy in an LSE event in October – watch it here.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

1 Comments