Bankruptcies have fallen sharply in richer countries because of the array of support available to businesses. This won’t last, warn Simeon Djankov (LSE) and Eva Zhang (Peterson Institute for International Economics), and governments should start planning for a surge next year – ideally by reforming their bankruptcy laws (as the UK has done) and lessening the burden on courts.

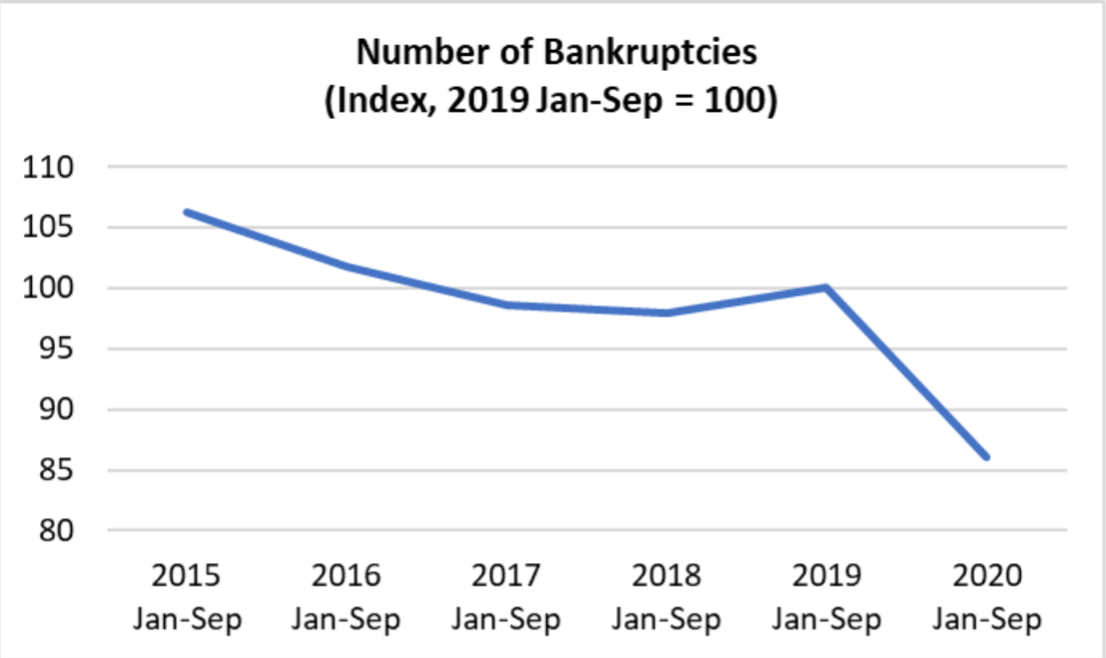

Economic crises usually bring an upturn in bankruptcies. Companies suffering big losses struggle to survive, and many fail. Yet during the first nine months of 2020, the number of corporate bankruptcy filings in most advanced economies – members of the OECD – fell by 13% relative to the same period in 2019, and even more relative to previous years (Figure 1). This decline in bankruptcy cases is a cause for celebration, as it demonstrates the success of the initial COVID response measures. On second glance, however, it brings worries too.

Figure 1: 2020 bankruptcy filings are 13 percent lower than in 2019

Note: The index is based on total number of bankruptcies in 25 advanced economies.

Source: Authors’ calculation using national data (accessed through Macrobond on November 24, 2020).

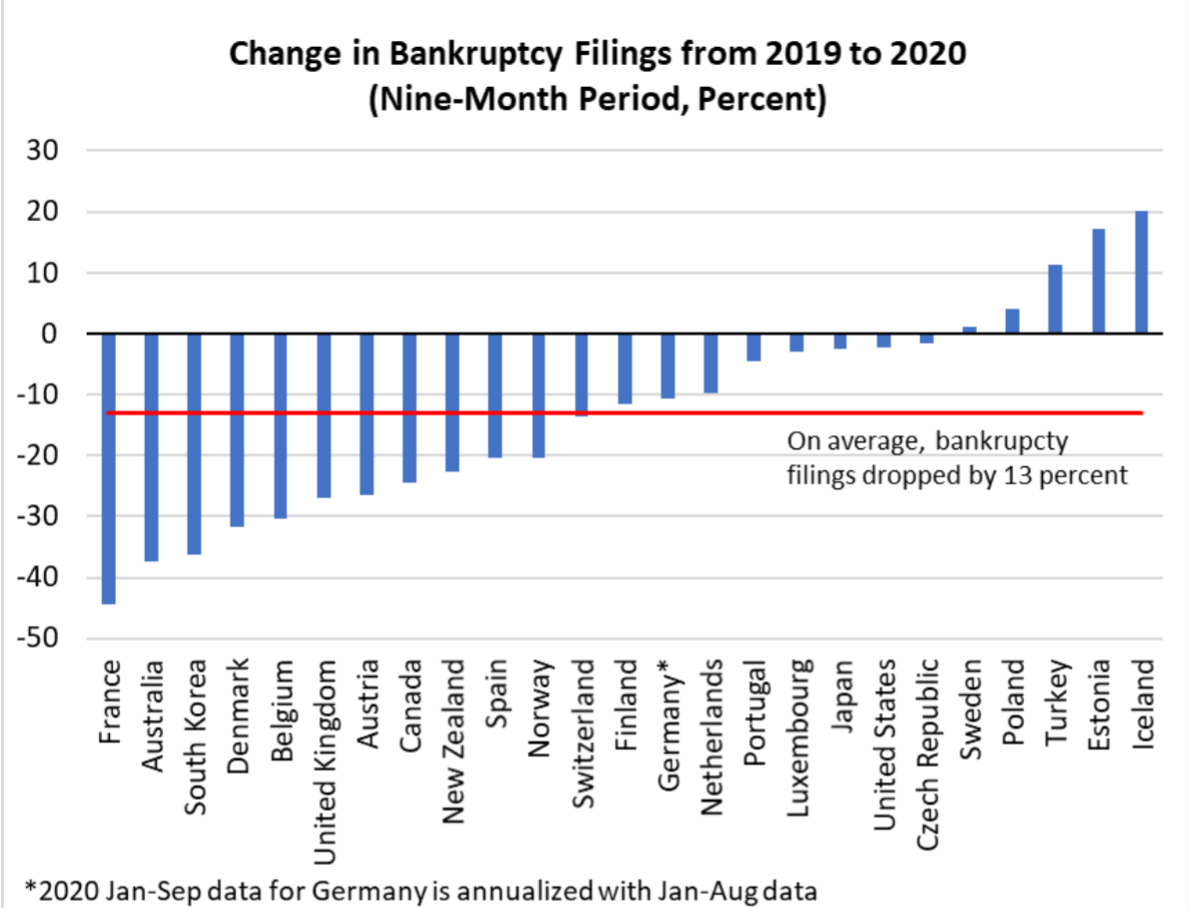

Bankruptcy filings have declined in 20 of 25 advanced economies

Monthly data is available on bankruptcy filings in 25 OECD economies (Figure 2). In the United States and Japan, these fell by 2 percent relative to last year. The other major economies show the same pattern of decline. In Germany, the fall is by 11 percent; in the UK, by nearly a third; in Canada, by a quarter (Figure 2). The largest decline is in France, by half, while several economies – primarily in Eastern Europe – show modest increases.

Figure 2: Bankruptcy cases decline across advanced economies

Source: Authors’ calculation using national data (accessed through Macrobond on November 24, 2020).

The reasons for this decline are twofold. The COVID-19 pandemic has induced governments in many advanced economies to finance job support programmes to assist workers, and to temporarily stop bankruptcy procedures – providing lifelines to keep firms alive through the crisis, at a time when premature bankruptcy can worsen the recession. For many employers and businesses, the government programmes have worked. Businesses have reacted by keeping employees on board or hiring new ones when restrictions on business operations became less onerous. In turn, the support keeps businesses open, in the hope that the economy turns around.

This availability of plentiful financial support to businesses cannot continue for long. Research by Olivier Blanchard, Thomas Philippon, and Jean Pisani-Ferry suggests that a large number of firms will need debt restructuring once government support programmes run out and the courts open up. Extensive reorganisation or liquidation procedures, which may work in normal times, will prove insufficient to service a large wave of insolvencies. Changes to existing regimes should be done now, before the wave comes. The UK has done just that and thus provides an example for other governments to follow.

The UK has added three features to its bankruptcy law

The amendments to the UK insolvency law, adopted in June 2020, add three features. First, these amendments introduce a two-month moratorium, during which the company benefits from a payment holiday from the majority of its debts. Second, the amendments allow the debtor to propose a rescue plan that can be forced onto every creditor if the majority of creditors agree. Third, suppliers are prevented from stopping deliveries once they find out that the debtor has trouble paying creditors, as long as the firm pays for its supplies on time—even ahead of bank creditors. Research on bankruptcy procedures around the world in the Journal of Political Economy shows that the type of changes the UK has enacted increase the likelihood firms will survive, as they continue operating during their restructuring.

Some economists are concerned that keeping insolvent firms alive will drain resources from the healthy parts of the economy. These fears are fundamentally misguided. Policies to force businesses to shut down permanently risk slowing down the COVID recovery. As businesses close down, they break a supply chain that affects other businesses, including in healthier sectors. Such breakage should be avoided as much as possible.

How to simplify bankruptcy law and be better prepared

The amendments to the UK bankruptcy legislation show the way for others to follow. They prepare for the tsunami of bankruptcy cases that are sure to come once the recovery packages ease out. In addition, governments may consider bankruptcy proceedings that involve less extensive court oversight, since the administrative capacity of their courts may not be able to handle the volume of cases. Simpler mechanisms, such as foreclosure with no or limited court oversight and floating charge, which essentially transfer control of the firm to the secured creditor, might be preferred. Restricting appeals might simplify bankruptcy proceedings and improve efficiency too. But even after such changes, courts are likely to be overwhelmed. A broader reform making out-of-court restructuring more appealing should be contemplated in countries with more sophisticated institutions.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.