How has crime evolved in England and Wales during the pandemic? Tom Kirchmaier and Carmen Villa-Llera (Centre for Economic Performance, LSE) look at the effects of lockdown and job loss on the kinds of crimes being committed, and the ability of police to detect them.

The global pandemic has transformed the way criminals engage in crime, and the way police respond. Lockdown measures have had at least two effects on the “supply” and “demand” for crime. On the one hand, by decreasing returns to legal activities, economic need may lead some to resort to criminal activities. On the other hand, the fact that fewer people leave the house has made committing certain crimes more difficult (ie the probability of being caught in a burglary is now presumably much higher). It has also made policing easier, which explains a higher number of arrests in drug-related crimes.

Restrictions on mobility imposed by the lockdown from March to May 2020 had an impact on the level and composition of crime. In England and Wales, crime was lower in all categories during lockdown, except for anti-social behaviour (35% above the mean, which includes offences related to breaching social distancing measures) and drug offences (17% above the mean). The latter is related to the increase in arrests, as the lack of people moving around made it much easier for police to track down dealers.

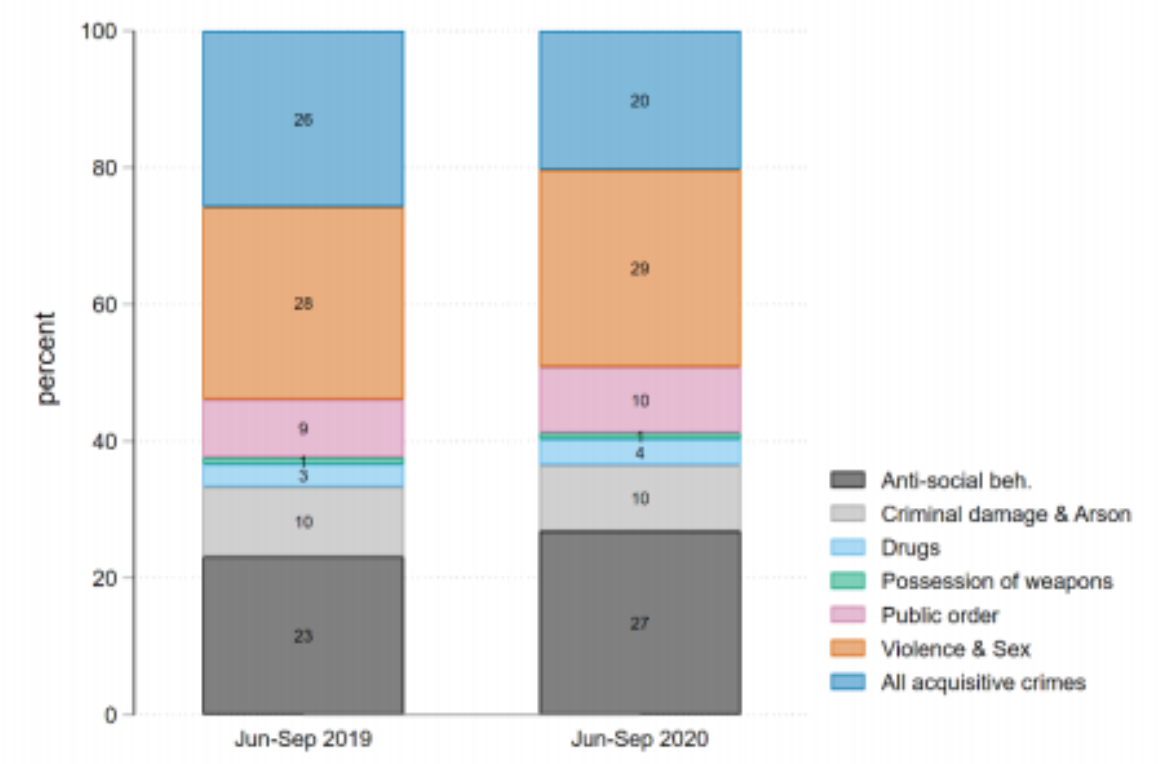

Beyond the levels in crime, there are important changes in the composition of total crimes. Figure 1 below shows the proportion of crimes in each crime category for the periods June to September in 2019, and 2020 across all LSOAs in England and Wales. This year the proportion of acquisitive crimes is much lower. On the other hand, the proportion of anti-social behaviour crimes is much higher, and there is a slight increase in the proportion of public order offences, as well as violence and sex offences.

Figure 1: Proportion of crimes in each category across England and Wales, for June-September 2019 and 2020 respectively

COVID-19 and the associated lockdowns increase the incentives to commit crime by decreasing returns to legal activities: the claimant count rose by 116% between March and September 2020 and more than 8.4 million jobs have been furloughed across the country since lockdown began. Offsetting this is the fact that fewer people leave the house, making committing some crimes – such as robbery – more difficult. Lockdown has also made policing easier, which explains a higher number of arrests in drug-related crimes.

The wide disparities in labour market outcomes highlight important spatial differences in the economic impact of the pandemic. These differences are associated with differing changes in crime rates. Areas with a higher increase in claimants during lockdown now have more anti-social behaviour crimes, 25% over the mean compared to the national 16%. Areas which entered the pandemic with above-median claimant rates have higher violent crime rates (30% over the mean).

The most vulnerable areas – those parts of the country with a high number of claimants pre-pandemic and with above-median increases in claimants since March – experienced higher antisocial behaviour, bicycle thefts and increased drug offences after the first lockdown. It is interesting to note the case of bicycle theft, which is in line with previous research on the economic value of goods and criminal incentives. During lockdown the value of alternative modes of transport increased, and with it the demand for bicycles. While some of the other crime categories serve as a sign of social unrest, the case of bicycle theft is one that highlights clear underlying economic motives.

While across the country social distancing measures have been reflected in a decrease in various other acquisitive crimes, this decrease is smaller in areas with higher claimant counts. They are characterised by lower levels of educational attainment, a proportionately higher Black and Asian population, a higher proportion of lone parents and worse health. The economic and crime effects of COVID are hitting the most vulnerable areas hard.

Understanding the spatial distribution of crimes and their correlation to economic outcomes is particularly important as we are now entering a period of renewed lockdowns around the world. Many more businesses may need to cease operations, and hence the prediction is that this figure may rise further in the coming months. The economic impact is more intense in certain parts of the country. In particular, the pandemic seems to have affected more strongly areas with lower educational attainment. These areas mostly concentrate in London, and the South and East of England.

Areas which are already characterised by deprivation are at risk of entering a difficult loop of poverty and crime. On the individual level, the economic disruption caused by COVID has affected more strongly those from poor families, and research has shown important disparities in educational opportunities. Other explanations of the geographical disparity can also be attributed to gender. The decrease in crime that has continued for some after lockdown may not last for long if a “wave” of social unrest builds up. Understanding these differences could be useful for targeted social policies.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. It is an edited extract from the Centre for Economic Performance COVID-19 Analysis Series No 13: COVID-19 and changing crime trends in England and Wales.