The International Monetary Fund is at the centre of the international financial safety net, but countries have failed to take up its support during the pandemic. If not during COVID, then when, asks Ousmène Jacques Mandeng (LSE).

The IMF saw early on the need for pandemic support. During its spring meetings in April 2020, managing director Kristalina Georgieva advertised: “[W]e have $1 trillion lending capacity — 4 times more than at the outset of the global financial crisis [and] have taken exceptional measures […] sought to maximise our ability to provide financial resources quickly […] to ease liquidity constraints and provide space for priority outlays […].”

Sure enough, annual world GDP fell by 3.3 percent year-on-year in 2020, and an emerging markets debt crisis is looming. These conditions should have catapulted the IMF into action. Yet it has been struggling to deploy its resources at scale, and its latest attempt to make a Special Drawing Rights (SDR) allocation of about US$650 billion may go the same way.

Put simply, IMF resources are not being used. The IMF lent only about US$100 billion — about 10 percent of its resources of about US$1,000 billion — during 2020 and early 2021. During that time, emerging markets and developing countries have mobilised just 0.1 percent of their total SDR allocations. This crisis should afford countries a mix of financing, in which IMF resources ought to be critical. While the IMF may argue that it stands ready to supply assistance, it needs to ensure countries actually take it. An international financial safety net that no one uses serves no purpose.

IMF lending

Between the end of January 2020 and January 2021, the IMF extended lending commitments based on my calculation by gross US$97 billion (Figure 1). During that period, a record 111 arrangements were approved. Excluding flexible credit lines (FCL) that are normally not activated, total new lending commitments were US$52 billion. The average amount approved, in percent of IMF quotas, countries’ financial stakes in the IMF, excluding FCLs has been 76 percent (or US$481 million), the lowest since the global financial crisis. By contrast, at the outset of the global financial crisis (September 2008 – September 2009), the IMF approved 34 arrangements totalling US$153 billion (and US$75 billion excluding FCLs) at on average 340 percent of quota, or US$2,415 million.

Figure 1: IMF credit outstanding

For some time, the IMF appears to have under-utilised its resources (Figure 1). Rarely has it lent at half of its capacity, gross of some prudential buffers. While some capacity constraints were alleviated through additional multilateral and bilateral borrowing arrangements, the IMF has mostly not been able to mobilise its resources fully, even in acute major global economic crises.

Special Drawing Rights allocation

SDRs are issued to IMF member countries and represent a perpetual credit line for freely usable currencies of IMF member countries. They are considered a supplement to foreign exchange reserves. If countries face an external shock, SDRs can be exchanged for dollars and used towards countries’ external debt services.

There are SDR204 billion (US$294 billion) in SDRs outstanding. SDR allocations are ‘cost free.’ Their distribution rests on the distribution of IMF quotas. Emerging markets and developing countries (including China and excluding the EU) have been allocated 37 percent of SDRs. In each allocation every country is given an SDR asset (holding) and an SDR liability (allocation). If a country holds fewer SDRs then allocated, its net holding is negative. Changes in net holdings show to what extent countries use them.

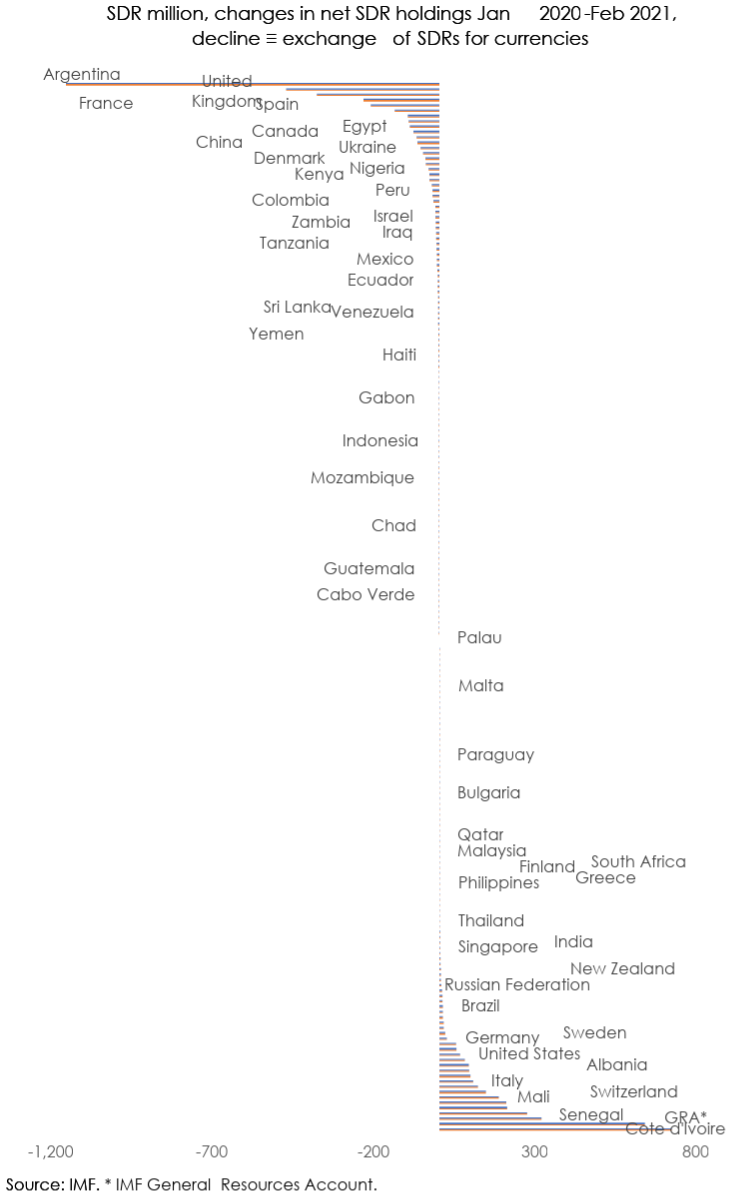

Figure 2: SDR usage

Between January 2020 and February 2021, emerging markets and developing countries including China reduced by SDR0.1 billion their net SDR holdings, out of a total of SDR76 billion in allocations (Figure 2). During the global financial crisis the mobilisation of SDRs (after a large allocation in August 2009) was similarly modest.

The IMF keeps insisting it wants a big bazooka. Yet it has failed to show it can use it. To be a central pillar of the international financial safety net, it needs to ensure its resources can be deployed fast and at scale in times of heightened distress. New arrangements, the Rapid Credit Facility and Rapid Financing Instrument, have already attempted to do that but are available only for relatively small amounts.

SDRs need to change if they are to be used. Allocations should be allowed to deviate from quota shares to enable countries in distress to get them, and be made more flexible — through, for example a large allocation envelope. They need to become more attractive as financial instruments and to go digital to leverage new technologies, making them more accessible for an expanded holder base, including private market participants.

The IMF’s recent track record suggests that it has fallen behind, becoming less visible and less used. Reforms are needed to ensure the IMF can play a more prominent role in the global economy. If it is not used during a pandemic, then what is it for?

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.