Bayanihan, the much-cherished Filipino spirit of solidarity, civic unity and cooperation, is not confined to the bayan (town or country). It transcends borders, hanggang sa ibang bayan (all the way to other towns or countries). Lalaine Siruno (United Nations University) explains how the Filipino migrant community in the Netherlands have done a great deal to help their undocumented compatriots, who are excluded from formal social protection mechanisms. But community solidarity alone cannot be enough.

There may be up to 30,000 undocumented Filipino migrants in the Netherlands. Most of them work informally for multiple households in the private domestic sector. Migrants say it is a physically demanding yet materially rewarding job, because they can earn between €10 and €15 per hour. Despite the double precarity that comes with being undocumented and working in the underground economy, many have been able to achieve socio-economic mobility for themselves and their family members in the Philippines.

However, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, many undocumented migrant domestic workers (UMDWs) were badly affected. Domestic work typically includes household chores like cleaning, doing the laundry, ironing clothes, gardening, other small repair and maintenance jobs as well as child or elderly care. On 12 March 2020, the Netherlands issued ‘work from home‘ guidance, and other restrictions to social life. Faced with social distancing regulations and gripped by fear and/or financial difficulties, many homeowners closed their doors.

I spoke to Marina, a Filipino UMDW based in Amsterdam (her name has been changed) in November 2020. She was ill with COVID at the time of our phone conversation and spoke through laboured breaths.

I got the virus, but I still consider myself lucky because most of my employers continued paying me even when they asked me not to report for work. I know many other Filipinos having a really difficult time because it’s no work, no pay. They’ve used up their savings to be able to keep sending money to the Philippines. Those with papers have nothing to worry about, the government supports them. Us without papers, we have to fend for ourselves.

I have spoken to many others like Marina and indeed her COVID experience is certainly not the norm. Eliza (name also changed) used to work a minimum of 40 hours per week. When we spoke seven months into the lockdown, she was still down to only 8 to 12 hours of work per week. Since she started working overseas about a decade ago, she has been sending money to her parents and siblings in the Philippines every month without fail. She still does, but since the pandemic the amounts are much smaller. Her savings have dwindled considerably but, Eliza said, there was simply no way she could stop:

It’s hard here, but it’s harder in the Philippines. Even public transportation there has been suspended. My brother’s a tricycle driver so now he has no job. The government doesn’t do anything to help. His children will have nothing to eat if I don’t send money. They depend on me and I can never turn my back on them.

UMDWs are not recognised as workers and their migration status precludes them from having access to formal social safety nets. The exclusion became very apparent when some local food banks were overrun and started requiring documentation from their beneficiaries, effectively restricting support to authorised residents.

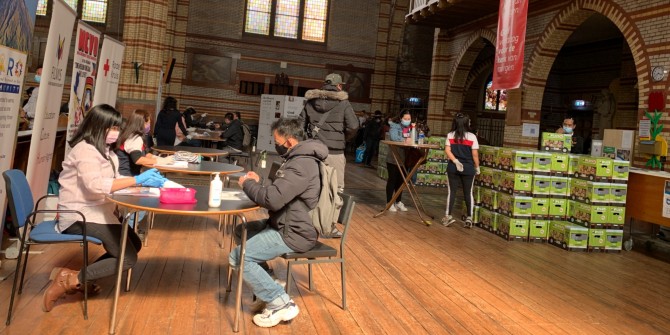

In May 2020, 16 Filipino community organisations based in the Netherlands formed the FILCOM-NL Alliance. Members tapped into their personal networks to collect donations in cash and in kind, all of which they distributed to their undocumented kababayan (fellow Filipinos) in need. The Embassy of the Philippines in The Hague also contributed to the effort. The biggest support is being provided by Red Cross Netherlands which has distributed food packs and nearly 54,000 grocery vouchers, usually worth €15, to people across the country whose incomes have been decimated by the pandemic.

For Filipinos, the distribution of emergency food aid has been consolidated into two main locations – one in Amsterdam, led by Filipino LGBT Europe with an average of 400 recipients every week, and another in The Hague organised by FILMIS, MCVO, and SARO Community with about 100 recipients. Some restrictions have been eased since the first lockdown, but life has not returned to normal for many UMDWs. Eliza has been receiving aid from the Red Cross since May 2020. The grocery vouchers enable her to get by while she sends her meagre earnings back home. “I don’t need expensive food and I could buy a lot with €15. I’m really grateful to the Red Cross and all the volunteers,” said Eliza.

A few of the volunteers in The Hague are themselves undocumented migrants. Contrary to the portrayal of them as powerless victims living in the shadows and barely surviving, many Filipino undocumented migrants in the Netherlands have long been active in mobilisation and empowerment efforts. They are also involved in many transnational activities – organising fundraisers for disaster relief, school supplies for children and other community projects in the Philippines. It seems that you can take away the Filipino from the bayan but never the bayan from the Filipino. They take the spirit of bayanihan wherever they go.

The volunteers told me that what they do is ultimately rooted in empathy. “I know what it’s like to need help and how difficult it is for the undocumented to get help. The Red Cross trusted us with this project and instead of being afraid, I know the right thing to do is to have courage and to do what I can for the community”, one said. “The police know we’re here every Sunday, so many undocumented migrants in one place, but we’re not committing any crime so why be afraid?” another added. “We are Filipinos, we do bayanihan, we help each other. Who else will show malasakit (a deep sense of compassion) especially when we are all outsiders here?” asked another volunteer.

This said, there are limits to bayanihan and the collective capabilities of migrant organisations and non-state actors that support them. Their COVID relief efforts have been immensely valuable, and the goodwill and generosity of volunteers and donors are a source of inspiration. However, as the UN points out, the effects of COVID are harshest for those already in vulnerable situations before the pandemic. The everyday precarity experienced by undocumented migrants demands a systemic, more sustainable solution. Migration is a complex social phenomenon but there is a straightforward, fundamental principle that should guide institutional policies — undocumented migrants are human beings with rights and dignity, and they deserve nothing less. Exclusion on the basis of migration status, much like the pandemic, requires more than a stopgap measure.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

I am happy that Filipinos bring the spirit of bayanihan where they are. I have seen many forms of bayanihan here in the Philippines. However, some efforts to help our kababayans became political when the supporters of the President started attacking those who are calling for systematic, evidence-based solutions. But these volunteers did not stop. One can give suggestions and act at the same time.

Bayanihan, of course, is not exclusive to Filipinos. Human beings who care for others are doing the same. But in a place where tayo-tayo and kanya-kanya also exist, bayanihan is an excellent cure.

I’m a foreigner in the Philippines and was very glad to have been living in a remote province during the pandemic. Well, it’s supposedly still ongoing because this administration still insists on wearing masks and having “health protocols” and an “alert level system” in place to this day. Even though the hospitals are about empty with covid cases.

I couldn’t imagine living in any city with the strict rules and police everywhere enforcing them.

My question is, how many news stories are done about those living day to day in poverty? That group of people must have been hit very badly. I do remember seeing images of police ignoring impoverished people not wearing masks.