You might expect to find that people trust governments more when they release timely information about the pandemic. But Michele Crepaz (NUI Galway) and Gizem Arikan (Trinity College Dublin) find that a lot depends on people’s prior views of the government.

At the height of COVID’s spread in Brazil in June 2020, Jair Bolsonaro’s government decided to stop releasing information about the daily increases in case numbers and deaths. They were simply wiped off the official website, prompting widespread disbelief around the world. Doctors, medical associations and state authorities mobilised to attack the move, labelling it ‘authoritarian’ and ‘unethical’, while civil society groups took to the streets to protest. On Copacabana beach the NGO Rio La Paz built symbolic shallow graves.

While it was extreme, Brazil’s example underlines the importance of information disclosure for sustaining legitimacy and trust in governments in times of crisis. The typical approach to the study of trust in government during the pandemic has been to highlight the evaluation of crisis management policies. However, one neglected – and in our opinion, relevant – perspective has been that of information disclosure as a tool in crisis management.

As early as April 2020, most European and Western governments established COVID-19 dashboards. Initially displaying only the number of cases and deaths, they soon became more sophisticated, with breakdowns by demographics and location, a summary of the daily PCR tests performed and the number of daily hospitalisations and ICU occupancy. The aim was to provide citizens, journalists and other stakeholders with information about how the state was performing in terms of crisis management and to reinforce levels of support, trust and legitimacy during the height of the crisis.

But whether the disclosure of detailed information about the pandemic really achieved these goals remains unknown. Simply looking at the trends in information disclosure and political trust across countries is problematic because it is impossible to disentangle the effects of information disclosure from other contextual factors that influence political trust. This is why we decided to study the effects of information disclosure in COVID dashboards on political trust with a survey experiment conducted in the Republic of Ireland in May 2020. Our findings have now been published as part of a special issue on COVID in The Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. They shed light on the complex relationship between information disclosure and political trust.

For our study, we created two replicas of the Irish COVID-19 Datahub, which was managed by the Department of Health (DPH) and used to release daily official updates on the state of the pandemic. One of the replicas provided detailed (high) information, while the other provided the limited (low) information that was available on the COVID-19 Datahub at the time. Respondents were randomly assigned to view the high or the low information version, or view nothing (control condition). We then assessed the impact of viewing the high or low information dashboard by comparing level of trust among respondents in the high and low versions to those who did not view the dashboard.

Our analysis demonstrates that information disclosure has no direct effects on willingness to trust the government in matters of crisis management or the government’s perceived capability to resolve the crisis. Neither the high nor the low information condition produced a statistically significant effect on the respondents’ levels of political trust compared to respondents in the control group. However, we find differences in political trust across groups, depending on respondents’ previous level of trust in government (in particular as far as the high information condition is concerned).

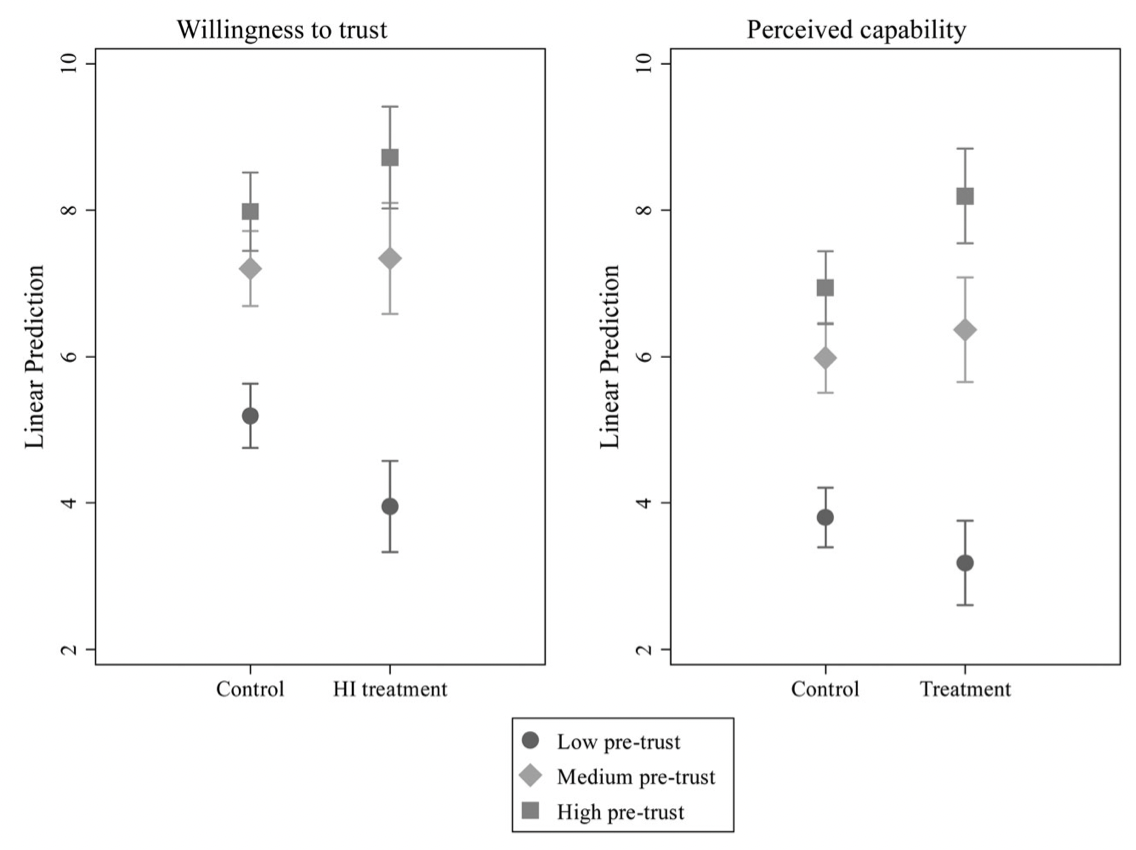

Figure 1 compares the high information condition to the control group for our two indicators of political trust. It shows that information disclosure about COVID increases political trust among respondents with already high levels of trust. This accounts for an increase in trust of 10%, keeping all other factors constant. Among respondents with low levels of previous trust, information disclosure had a negative effect, accounting for a 6% drop in political trust (all else being equal). Overall, Figure 1 shows signs of polarisation, whereby information disclosure has opposite effects for respondents with low and high levels of previous trust. This has the detrimental effect of widening the gap in levels of political trust between the two groups.

Figure 1 – Predicted marginal effect of High Information condition (vs Control) on indices of political trust with 95% confidence intervals. Source

Why does this polarisation occur? We argue that this is because the consumption of information is a motivated process, with individuals seeking to find – in the disclosed information – consistency with their prior beliefs. This is why information disclosure produces contrasting effects, depending on respondents’ prior level of trust in government. Individuals with high levels of prior trust want to maintain or reinforce existing levels of political trust when processing the disclosed information. But individuals with low levels of prior trust react negatively to disclosed information with a consequent drop in political trust (called the backfiring effect of transparency) in political trust. This may be because, in an effort to maintain their prior beliefs about the government’s untrustworthiness, these individuals may end up concluding that the information is not trustworthy or accurate, or may focus on pieces of information that allow them to produce arguments against the government’s trustworthiness.

These findings imply that in their efforts to gain the trust and confidence of citizens, governments may run the risk of triggering further distrust among citizens who are already sceptical of their actions. However, there is a more optimistic interpretation of these findings. Governments can capitalise on the unusually high levels of trust seen at the beginning of the crisis by providing detailed information to their citizens. The ‘rally-round-the flag’ effects observed in many European countries and the United States during the first wave of COVID might have been partially sustained by their governments’ decision to be transparent about crisis management and create open data tools such as data dashboards.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.