Is the welfare state really a drain on the economy? Or can it be our saviour during recessions? Max Mosley (LSE) shows that as most welfare recipients are highly responsive to changes in temporary income, changes to benefits will have a disproportionately strong economic effect. This means raising levels during recessions can in fact act as a more powerful form of fiscal stimulus. Conversely, cutting them will have a negative effect on the economy – which has implications for the end of the £20 Universal Credit boost.

At the onset of recessions, like those we’ve seen caused by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, there are two somewhat predictable stages in how governments across the world react to their respective economic situation. Given worldwide interest rates are already constrained at zero, the first stage is the use of fiscal stimulus – such as direct cash payments or tax cuts – taking a frontline role in boosting economic activity. Governments turn to paying for this stimulus in the second stage, which has frequently taken the form of cutting the size of the welfare state, as was the case after 2008 and is set to be in 2021. (The planned end to the £20 Universal Credit boost reflects this strategy.) This naturally implies a trade-off between social and economic objectives, which swings towards the latter when times are tough.

Yet there appears to be an inconsistency.

Why is it that we see the welfare state as a ‘drain’ on the economy, but direct cash payments as an essential economic instrument, when they are conceptually identical? By this logic, surely the ‘welfare state’ is just the world’s largest cash-transfer programme. Cutting it to pay for cash payments to the population is like taking one step forward but then taking the same step back. Does lowering contributions constrain economic activity in the same way a tax cut does? What if we instead did the opposite and used fiscal stimulus to raise welfare contributions? Would this make fiscal stimulus more or less effective in stimulating activity? These are the questions my recent paper with the CEPR sought to answer.

To know the economic effect of raising or lowering welfare contributions, we need to know how ‘responsive’ recipients are to temporary income changes. Not every household changes their consumption when their temporary income changes. Some economists – notably John Cochrane – have long maintained that most households are ‘unresponsive’, as they have alternative sources of liquidity (such as their savings, their credit cards, their home equity and perhaps some non-market investment income) to draw on.

However, households which do not have the same access to liquidity as the above (such as those with low savings, without credit cards, who are unemployed, don’t own their own home or have investment income) have been consistently found to be highly responsive to changes in temporary income. These households have been found to spend around 80% of income increases, and are even more responsive to negative income shocks.

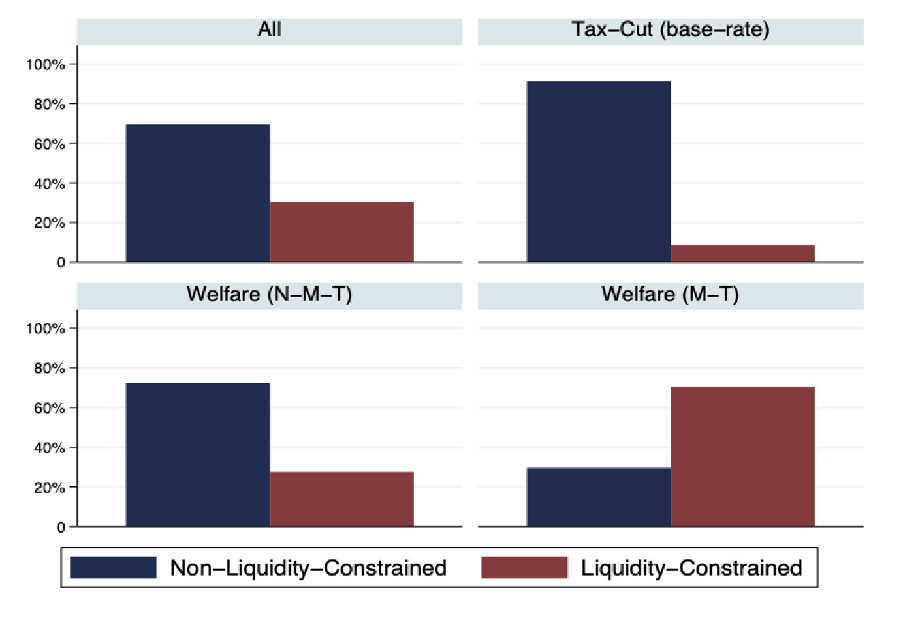

So are welfare recipients more or likely to be liquidity-constrained and therefore responsive to temporary income changes? Given the fact that eligibility for means-tested programmes means a household has less liquidity, do existing welfare programmes target these highly responsive, liquidity-constrained households? Using microsimulation model UKMOD, I show in Figure 1 that despite the fact that only 30% of all households are liquidity-constrained, 71% of means-tested welfare recipients are. This is a huge difference, which has vital implications for how governments approach macroeconomic recovery.

Figure 1: Liquidity-constrained recipients, by welfare and tax bands

Source: Author’s calculations through UKMOD. NMT and MT stand for non-means-tested and means-tested welfare programs respectively.

Firstly, cutting contributions to welfare recipients will have a stronger than usual contractionary effect on economic activity, as the vast majority of welfare recipients will have to cut consumption as a result. I estimate the economic consequence with a New Keynesian macroeconomic model, finding a negative impact multiplier (that is the ratio of output change in welfare levels) of 1.8. This means for every £1 cut in welfare contributions, we lose 1.8 in output.

Secondly, transferring cash to the general population is inherently inefficient as only 30% of the population is responsive to fiscal stimulus. Stimulus through tax cuts, even to the lowest earning households, will have even less of an effect, as a tiny proportion of those who would gain will be responsive. If we instead directed this stimulus to welfare recipients, who are far more responsive to stimulus, I find positive impact multipliers of 1.5 using the same model as above. This means for every £1 of contributions raised, we gain 1.5 in output.

Critics of fiscal stimulus are therefore right to describe it as ‘circumscribed’, as only a small proportion of households are liable to spend the windfall – even less if it is through a tax cut. But the welfare state itself can be the answer to this inefficiency, as it is by nature already set up to transfer cash to the very households who are liable to spend it. If welfare recipients are disproportionately sensitive to temporary income changes, we can strengthen the effects of fiscal stimulus by raising welfare levels, and cutting contributions will have a strong contractionary effect on the economy.

What is abundantly clear is that the popular narrative that welfare is a drain on the economy is false. Not only does cutting welfare have a strong contractionary effect on output, but we can also strengthen fiscal stimulus by raising welfare levels to stimulate economic activity. We can also keep the valuable social advantages from welfare programmes, while simultaneously achieving powerful economic outcomes by raising welfare levels. The dilemma between social and economic objectives – long stated by many – is in this case entirely self-imposed.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

Wow.. what a brilliant and thoughtful way to look at the ever constant debate of the welfare state. Hats off to you Max Mosley for thinking outside the box. An an excellent article.

Maybe we need to set up a fiscal committee that makes these decisions independently or uses automated tools like the sahm rule to decide when to cut and when to expand welfare depending on business cycles. I think that if we give this power to politicians pro-cut politicians would want to gut the welfare system too early and pro-expansion politicans would never cut welfare to reign in the economy if the economy starts generating inflation due to surpassing its potential output. Also although there are some fallacies with the ricardian equivalence, I think that it can also be used to explain why tax cuts even for the poor may have low multiplier effects.