Over the last year LSE’s Shaping the Post-COVID World initiative has explored the direction the world could, and should, be taking after the pandemic. In this first special summary piece, Bob Ward of LSE’s Grantham Research Institute on Climate and the Environment looks back over the last year of discussions and, as COP26 begins, sets out the actions governments must take now to ensure sustainable growth.

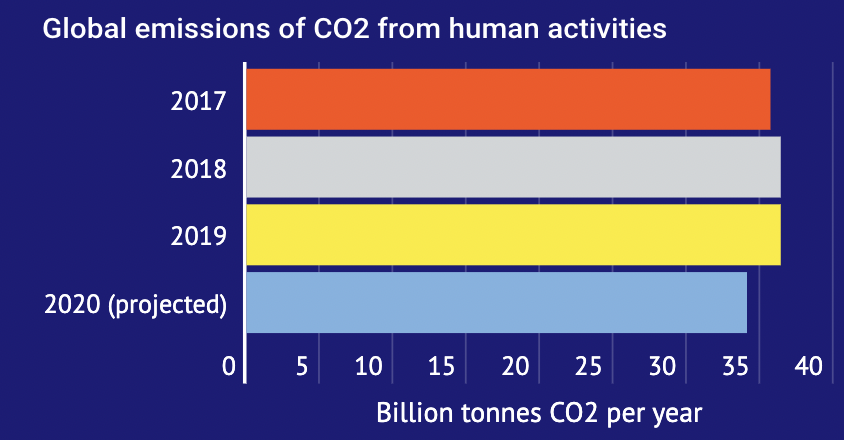

When people stayed at home during lockdowns, carbon dioxide emissions fell. This is unlikely to last. Many countries are choosing to recover from the pandemic by burning fossil fuels again.

There is a powerful case for a sustainable, inclusive and resilient recovery from the pandemic to tackle the threats of infectious diseases, biodiversity loss and climate change. Economic growth is not incompatible with tackling these crises.

The case for investment

The Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action set out in July 2020 how finance and economic policies could both stimulate growth and tackle climate change. In an independent report requested by the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson in June 2021, Professor Lord Nicholas Stern and colleagues at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment argued for an increase in annual investment equivalent to 2% of GDP by the G7 countries, focused on zero-carbon and climate-resilient infrastructure, to drive the transformation to a sustainable, inclusive and resilient economy.

Reasons for hope

There are signs that some countries are pursuing a green recovery from the pandemic.

The top three emitters

China

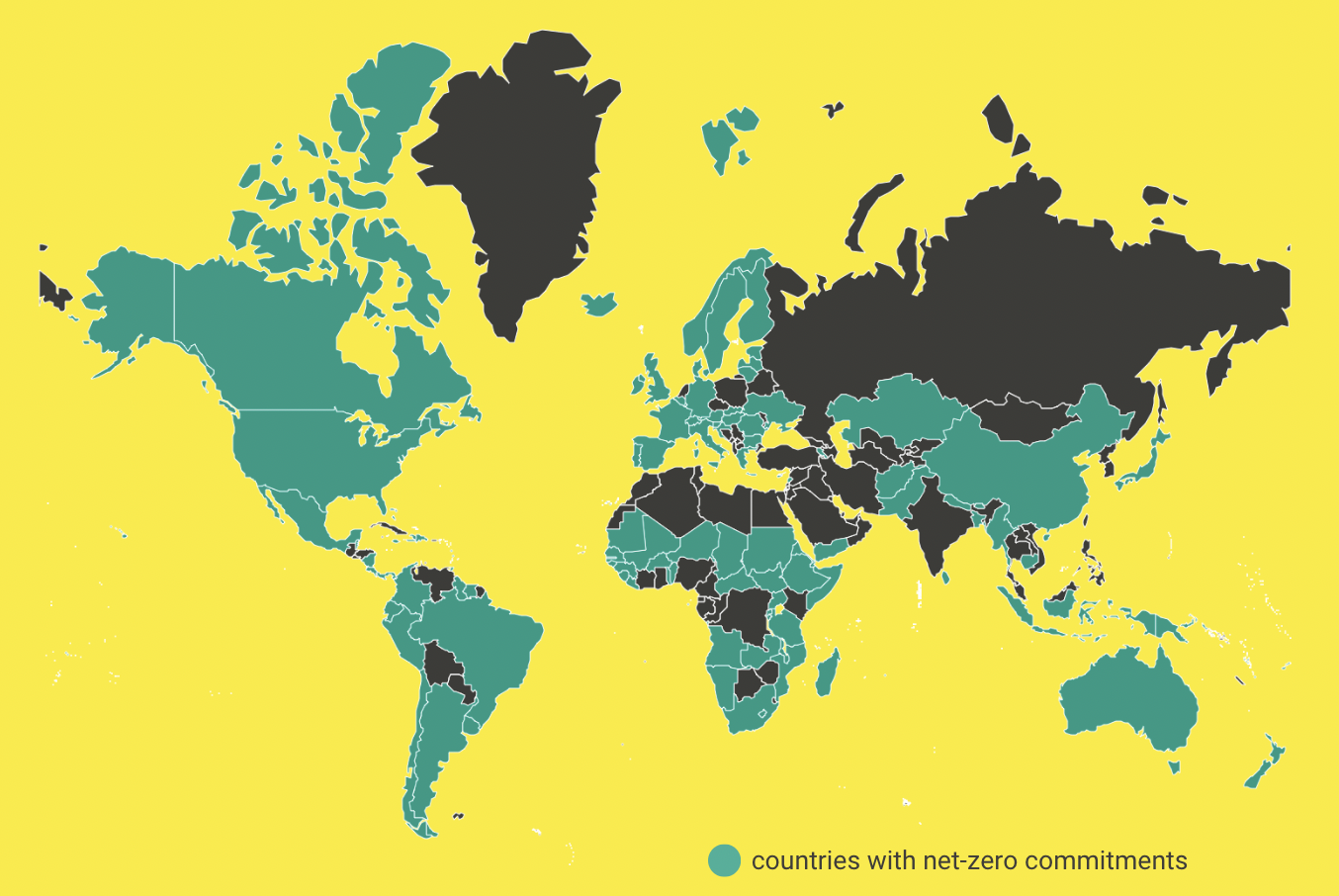

In September 2020, President Xi Jinping made a historic pledge that China would achieve carbon neutrality, or zero emissions, before 2060. It raised hpes, which so far have not been realised, that China may also bring forward the peak in its annual emissions from 2030 to 2025 and achieve it by the end of its 14th 5-Year Plan.

USA

One of US President Joe Biden’s first acts after inauguration in January 2021 was to initiate the process to rejoin the Paris Agreement after Donald Trump left it.

Biden has also committed the US through its nationally determined contribution to the Paris Agreement to reduce its annual emissions by 50 to 52 per cent by 2030 compared with 1990, and set a domestic goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050. His administration has taken a range of measures to sweep away Trump’s climate change denial, but the prospects for radical action may be limited by ongoing opposition from the Republican party in Congress.

European Union

The European Union, the third largest source of annual emissions of greenhouse gases, aims to promote a ‘greener, more digital and more resilient Europe’ through its €806.9bn NextGenerationEU recovery plan.

Together with its Multiannual Finance Framework, between 2021 and 2027 the EU intends to invest almost a third of its finances into a European Green Deal, which will help it to reach its targets of reducing its annual emissions of greenhouse gases by 55 per cent by 2030 compared with 1990, and net zero emissions by 2050.

United Kingdom

The UK set its domestic target for net zero emissions by law in 2019, and had already reduced its annual emissions by about 44 per cent by 2019 compared with 1990, while its GDP has grown by more than 75 per cent over the same period.

Many other countries, cities and companies have now also pledged to reach net zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050 and the finance sector, including central banks and investors, has also embraced the target.

Tipping points

This follows the publication in October 2018 of a report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which warned of the risks, including the potential breach of thresholds or tipping points in the climate system, of missing the Paris Agreement’s temperature goal.

The Agreement commits countries to ‘holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2C above pre-industrial levels and pursing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.’

What do we need to do?

According to the IPCC, to have a reasonable chance of avoiding warming of more than 1.5C by 2100, we must:

By 2030: Cut annual global emissions of CO2 by 45% compared to 2010

By 2050: Reach net zero emissions of CO2, balancing any residual emissions by removals through planting more vegetation or artificial methods of removing CO2 permanently from the atmosphere.

A bleaker outlook

We are not on track to meet our targets.

The proliferation of net zero pledges has not been accompanied by a commensurate increase in the ambition of policies for the next decade. Many countries, including 11 of the G20, have still not submitted more ambitious pledges for emissions cuts by 2030, ahead of the 26th session of the Conference of Parties (COP26) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The case for sustainable growth in the UK is well established but the Climate Change Committee has warned that the UK is currently not on course to meet net zero by 2050.

Even as policymakers hesitate to adopt strong commitments, the impacts of climate change are becoming ever more apparent in the form of frequent and intense weather events, including heatwaves, tropical cyclones, wildfires and extreme rainfall.

We must act now

Climate change is already affecting every inhabited region across the globe with human influence contributing to many observed changes in weather and climate extremes

(IPCC, August 2021)

This article is part of LSE’s Shaping the Post-COVID World series, convening a debate about the direction the world could, and should, be taking after the crisis, and how social science can get us there, with the LSE COVID-19 blog and LSE School of Public Policy.