Countries with the fiscal means to pay people to stay at home had an advantage during the pandemic. But there is also an important association between levels of interpersonal trust and COVID mortality, say Tim Besley and Chris Dann (LSE) — and this aspect of state capacity could prove to have been very important.

Despite being ranked as the best-prepared countries for health crises, high-income countries like the US and UK have had high case and mortality rates during the pandemic. In an effort to explain this, policymakers and commentators have argued that ‘state capacity’ for fighting public health crises is less relevant in terms of understanding government responses to the pandemic. But we believe that this is a poor way of framing the debate on policy towards managing COVID.

State capacity is defined as the institutionalised capability of the state to implement policies that deliver benefits and services to households and firms. This idea applies directly to health policy: if a government wants to respond to a pandemic effectively, it must have the organisational structures in place to do so. A common metric of state capacity is “fiscal capacity”, which refers to the ability of the state to raise revenues that fund government policies. Hence, tax revenue as a share of GDP is a standard measure (of one of the dimensions) of state capacity.

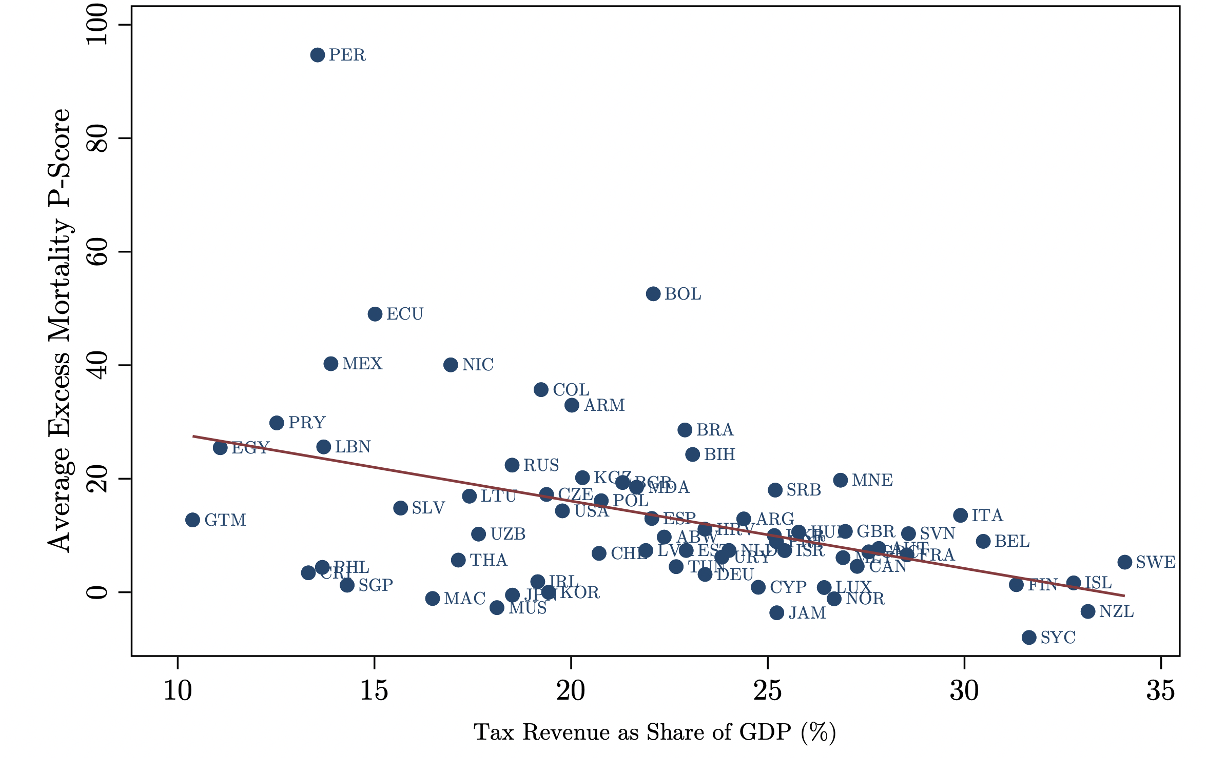

Plotting tax revenue as a share of GDP against 2020-21 average monthly excess mortality “p-scores” from Our World in Data shows a strong negative correlation. These p-scores help account for population differences across countries, representing the percentage difference between reported deaths and (counterfactual) projected deaths in “usual times”.

Figure 1: Fiscal capacity and excess mortality p-scores

Source: Our World in Data and the International Center for Taxation and Development. Note: Trend line is robust to using media 2020-21 excess mortality p-scores versus monthly average. Trend line is also robust to omitting Peru as an outlier. Tax revenue as a share of GDP refers to 2016 levels as the latest observation from Besley, Dann and Persson (2021).

The association shown in Figure 1 goes against the idea that state capacity is not relevant to understanding government performance during the pandemic. It also focuses the mind on plausible mechanisms for why excess mortality has generally been higher in countries with low state capacity — examples being Peru, Ecuador, Lebanon, among other developing countries — consistent with the general leftwards triangulation seen in Figure 1.

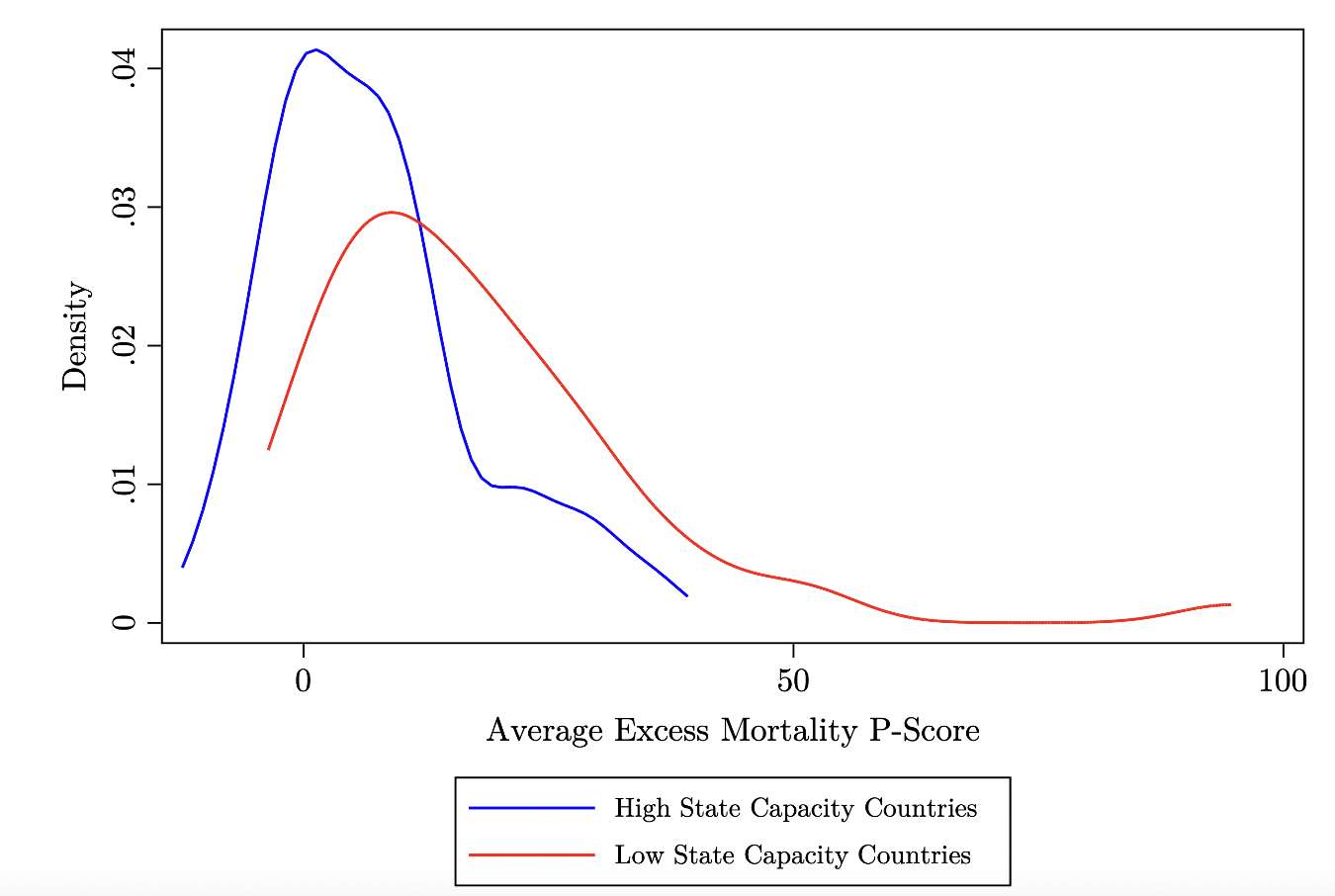

One view is that state capacity and the strong institutional structures that enable its development, such as checks and balances on executive power, protect countries against shocks. Engineering and biology have developed the idea of “robust control” to think about this, but it can also be applied in political economy. High state capacity enables countries to respond with the capacity to tax, supporting interventions which spend and regulate appropriately. Figure 2 conveys this idea. Although the modes (i.e. peaks) of the low-state capacity and high-state capacity distributions are not entirely distinct, we see a much longer right-tailed distribution for countries with low state capacity. This conveys much greater variation in poor performance to the pandemic, as proxied for by excess mortality. We see this pattern in the heterogeneous performance of democracies and autocracies on a variety of development outcomes.

Figure 2: Distribution of excess mortality p-scores by state capacity levels

Note: high state capacity is defined as countries in the 75th percentile or above of tax revenue as a share of GDP.

One COVID-specific example of this “robustness” concerns fiscal capacity. A strong fiscal state allowed the UK to rapidly implement the furlough scheme at the height of the onset of the pandemic. Other advanced countries have also implemented unprecedented social safety net measures to protect workers, in addition to providing massive liquidity support for firms. Such endeavours could only have been achieved in countries where the state had the capabilities to do so. In developing countries with large informal sectors, there is less scope for the state to protect workers through formal measures. This may explain why Peru, among other Latin American countries, has performed so poorly throughout the crisis.

Beyond the more tangible aspects of state capacity, a growing literature in political economy stresses the role of norms and values as another fulcrum of state effectiveness. Sometimes this is referred to as “civic culture”. Even if governments have the capacity to implement policies, a citizenry that cooperates with such actions through mutual trust can help reinforce these directives. This is especially important in liberal democracies when the coercive power of the state is substantially more constrained.

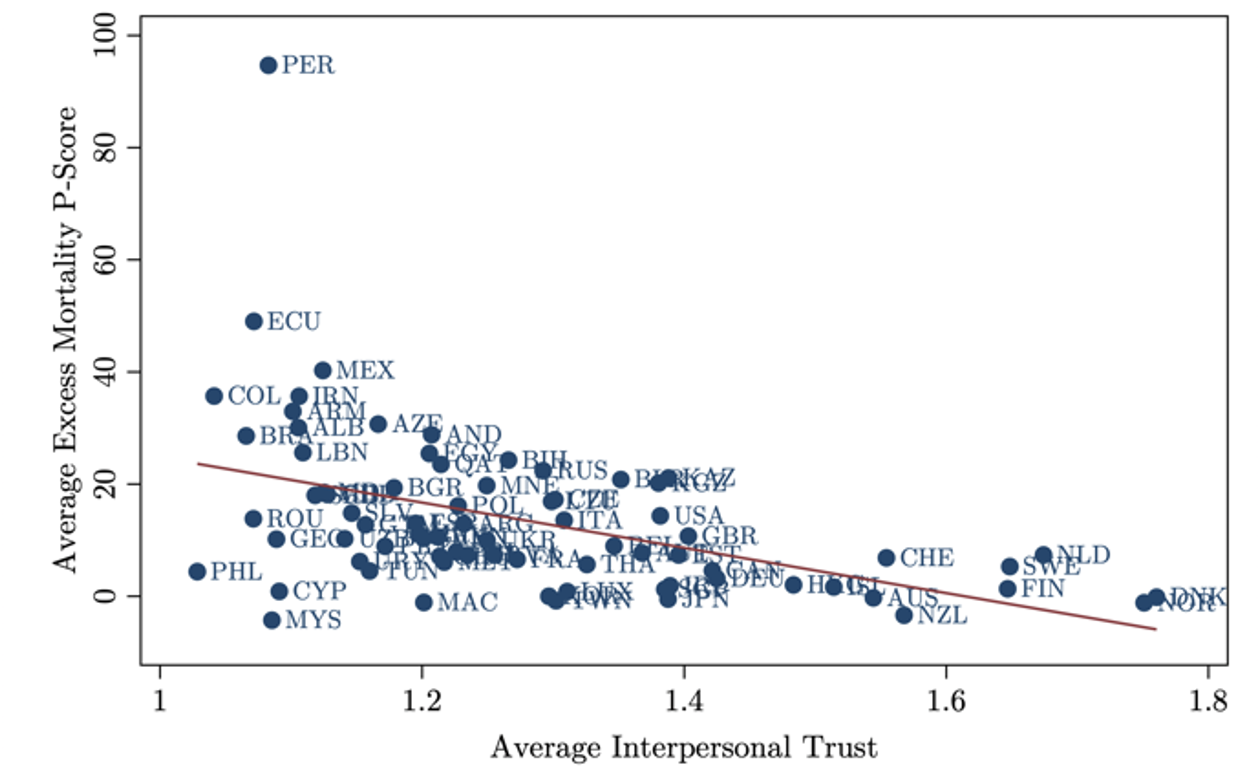

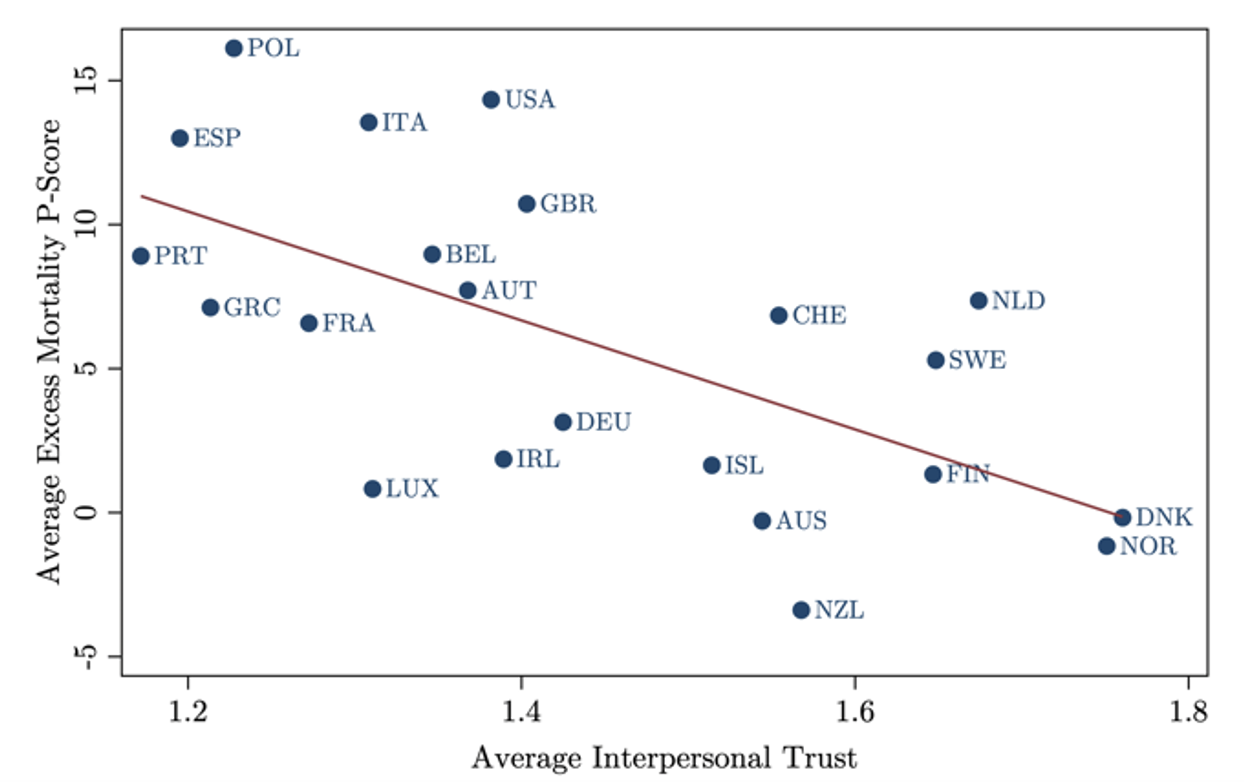

Figures 3 and 4: Interpersonal trust and excess mortality

Note: data stems from the Our World in Date and World Values Survey (WVS). Trend line is robust to using median 2020-21 excess mortality p-scores versus monthly average. Trend line is also robust to omitting Peru as an outlier. Trust is measured as the WVS question: generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people? Higher values mean higher levels of trust. We use the most recent observation from the WVS per country.

Note: data stems from the Our World in Date and World Values Survey (WVS). Trend line is robust to using median 2020-21 excess mortality p-scores versus monthly average. Trend line is also robust to omitting Peru as an outlier. Trust is measured as the WVS question: generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people? Higher values mean higher levels of trust. Sample of countries refers only to 22 advanced capitalist democracies (ACDs).

As shown in Figure 3 using data from the World Values Survey, countries with high levels of interpersonal trust have tended to perform better during the pandemic. Although the mechanisms are not clear, if governments can rely on mutual reciprocity concerning COVID regulations, there is less need for the government to enforce sanctions. This has been particularly important in lockdowns. When the benefits of lockdown are public but the costs are private, there are clear incentives to “free-ride”. But if there is mutual trust in others to follow the rules and reciprocate in pro-social behaviour, such as wearing a face covering, then this can bolster the intended effects of government policy. This has been noticeable during the latest Omicron-driven wave of the pandemic, where countries are wary of reintroducing strict lockdown measures rather than trying to encourage responsible behaviour.

The general trend between trust and excess mortality is not driven by the inclusion of developing countries in the sample. Even when we home in on advanced capitalist democracies, which are more similar in background economic characteristics and institutional features, we still find a strong negative correlation, as we see in Figure 4. Of course, a number of potentially confounding factors co-determine lower excess mortality and higher levels of interpersonal trust, such as differences in overall welfare system expenditure (notice the position of the Nordics). But it is striking that among the group of countries deemed the best prepared for the pandemic, we still see this excess mortality-trust association at work.

New academic contributions evaluating state capacity vis-à-vis COVID outcomes are emerging. But it is important to recognise how ideas from this large research agenda on state capacity factor in to understanding the crisis itself. The observation that high-income countries had higher than expected COVID cases and death rates does not undermine the fact that state effectiveness is important in managing pandemics. But much more work is needed to get to the bottom of what drives different patterns in the data. Efforts such as the EU-funded Horizon 2020 project PERISCOPE are helping to make this happen.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. The Periscope project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme, under the Grant Agreement number 101016233.