Young people’s mental health and wellbeing suffered during the pandemic, and we do not yet know what the long-term consequences will be. Annette Bauer (LSE) looks at which groups have been most affected and calls for support that extends beyond 2022.

The standard response of most governments to the spread of COVID has been to impose lockdown measures. These have had a particularly disproportionate impact on children’s and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. This impact is something that many have argued is unfair, with the virus posing fewer physical health risks to this part of the population.

More generally, the strong focus on the physical impacts of the virus might have inhibited the ability of many, if not all, governments to recognise the impact on mental health and wellbeing that policies such as school closures and social contact restrictions entailed. In the future, a stronger focus on this issue during this pandemic and possible future health emergencies might lead to the development of more balanced and nuanced government measures, including some that prioritise the needs of children and young people.

Addressing mental health and poverty together

The link between poverty and mental health and the vicious cycle which it inculcates is well established

National data clearly reveals that the pandemic did not affect people’s mental health equally. Instead, certain groups, including children and young people — in particular those living in or at risk of poverty — were much more affected.

Children’s and young people’s mental health has been particularly affected during the crisis. It is likely that some of these impacts will be long-term, especially when those affected find it harder to get jobs or their long-term earnings suffer. Children or young people living in or at risk of poverty are particularly likely to be affected. The link between poverty and mental health and the vicious cycle which it inculcates is well established, as is the potential for it to lead to substantial long-term harms. For example, poverty can adversely affect children and young people’s brain development and functioning and lead to stress-driven or otherwise impaired decision making, in which future benefits are discounted over more immediate rewards, thus increasing the likelihood of failure in the education system or in future unemployment.

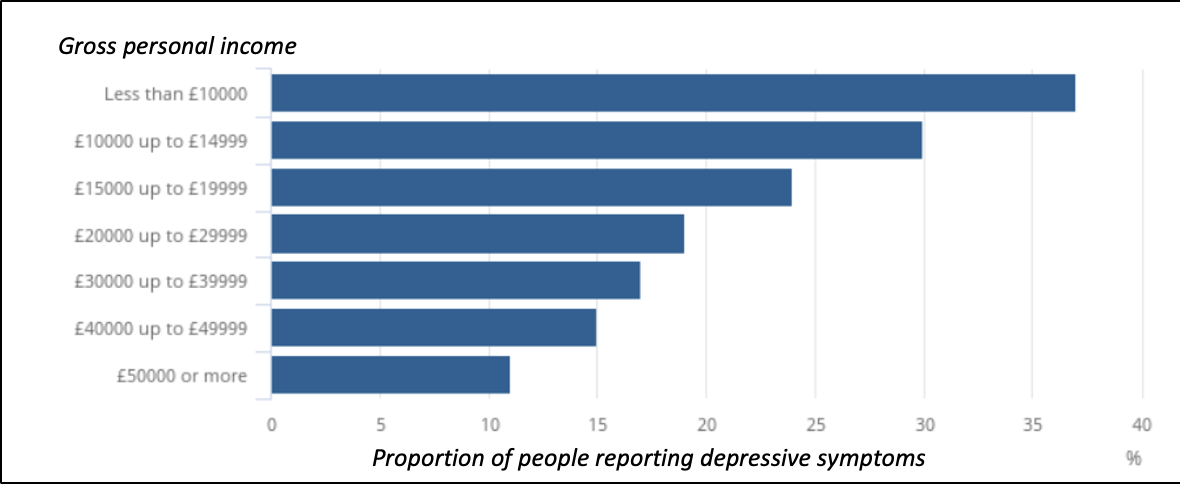

Among the general population, depression rates were 11 percent higher in deprived than in the least deprived areas (28 percent v 17 percent). Whilst one in ten of those earning £50,000 or more experienced depressive symptoms, the prevalence for those earning less than £10,000 a year was four in ten. Figure 1 shows this strong relationship between depressive symptoms and gross personal income, with the analysis of longitudinal household survey data showing that financial difficulties were a main predictor for deterioration in mental health during the course of the pandemic.

Figure 1: Relationship between depression and income during the COVID pandemic: Percentage of working age adults with depressive symptoms by gross personal income, Britain, 27 January to 7 March 2021

Source: Office for National Statistics – Opinions and Lifestyle Survey)

Interventions that seek to reduce or address poverty, such as cash transfers, can improve the chances of young people doing well at school and staying healthy. They also have the potential to positively influence mental health, although we need more evidence on how to enhance those effects, for example through integration with additional mental health information and support.

Opportunities for integrating mental health into poverty alleviation measures include:

- welfare measures specifically target young people at risk of mental health problems;

- those (re)designing and improving poverty alleviation programmes consider the potential impacts on young people’s mental health;

- using evaluation frameworks that include mental health;

- programmes make mental health education and promotion resources available; and

- they offer and promote mental health treatment.

Debt advice programmes, which seek to alleviate poverty by supporting people to pay off their debt, are a commonly used welfare measure and have the potential to address children’s and youth mental health. The scale of the problem and therefore potential benefit of intervening is particularly evident for countries like the UK, where an estimated 2.4 million children and young people in England and Wales live in households with ‘problem’ debt, of whom a fifth are thought to have low wellbeing. Studies have shown that debt advice programmes can alleviate the mental health effects associated with debt — for example, through increasing feelings of hope and optimism.

Addressing mental health and social support together

Children’s and young people’s access to their regular social networks has been affected through measures such as school closures. Loneliness among children and young people increased sharply during the pandemic, with one in three reporting they feel lonely often or most of the time. However, not all children or young people have been equally affected. Those with pre-existing mental health problems, living in or at risk of poverty, or from Black, Asian or mixed ethnicity have been more likely to experience loneliness.

Given that childhood and adolescence are important years for building and developing social skills and relationships for the future, it is plausible that the disruption to social life, including at school or workplaces, might have long-term impacts for some children or young people. Evidence from lockdown measures in response to earlier pandemics also suggests that social isolation and loneliness can persist after enforced isolation ends.

The close link between mental health and social networks, and the support perceived as coming from such networks, is well established. Most research has investigated the protective effects of social support, measured in terms of social contacts or perceived loneliness, or the negative effects of a lack of it, on mental and physical health. Health policies in the UK have begun to pick up on those findings, and introduced responses, including a loneliness strategy. In addition to funding allocated under pre-COVID policies, the government has, in its pandemic responses, invested £31.5 million in organisations supporting people who experience loneliness.

However, there is currently limited and inconclusive evidence about what works and is good value for money in this area. This can lead to well-intended but potentially oversimplified recommendations or interventions, such as those that postulate or assume that simply increasing numbers of social contacts will automatically reduce loneliness. While those suggested actions might have benefits for some, they might not be feasible or appropriate for the populations most at risk of loneliness, including marginalised children and young people. To successfully mobilise social support for vulnerable children and young people, interventions require the use of complex and long-term processes that endeavour to build hope, self-esteem, and trust. While often assumed to be low-cost, interventions in this area, if they target disadvantaged groups, require substantial resources in the form of professionals’ and volunteers’ time. Some required joined-up efforts from communities.

Current and future policy direction

England’s COVID-19 Mental Health and Wellbeing Recovery Action Plan sets out plans to put in place training for teachers to recognise and support children and young people with mental health problems at school. It also includes plans for the provision of additional mental health support to young people not in education, training, or employment. However, the plan only covers 2021 and 2022. Long-term responses are required that address children’s and young people’s mental health, especially given the impact the pandemic has had on poverty and social support.

Experiences from past health emergencies and economic crises show that mental health can become a priority of system reform during those times, and that there are opportunities for change. This includes designing public sector systems that are fit for purpose for future health emergencies. The recent LSE-Lancet Commission on the future of the NHS after COVID recommended incorporating mental health strategies into health emergency plans. Research on mental health and wellbeing has an important role in informing future responses to health emergencies. The pandemic has highlighted the need for quick and effective processes for translating evidence into practice. Early feedback suggests that partnerships between policy, research and practice can play an important role in effective emergency responses.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. It is an edited extract from Bauer, A., 2021. COVID-19 and Mental Health and Wellbeing Research: Informing Targeted, Integrated, and Long-Term Responses to Health Emergencies. LSE Public Policy Review, 2(2), p.6.

Extra Effort to help Parents/Adults too. Youth -Adult -Partnerships to Bridge the Gaps.

-True the pandemic has had a serious impact on young peoples mental well being especially around anxiety , depression, poor sleep due to changes in routine patterns and social isolation.

Worse still is the new but difficult dynamics in the household which are manifested in defiance and conduct issues which parents have found hard to deal with and there’re feeling helpless. This in some cases has explained increased indulgence in alcohol use risking increase in domestic violence.

My contributing to this article is a need to look at this new challenges of increased mental health needs in YP from point of view of helpless parents and therefore be able to think of what help in form of resourcing them with basic skills of identifying early and knowing when they need help to help their children. Anecdotal evidence exists that parents who accompany their kids to A&E with MH needs and self harm come to realise that they were not aware , that their kids were hurting but thought their parents will guess. Most parents see the behaviours , the end point. But some on looking back it is the small gaps in frequency and quality of communications, The right questions. Vs making guesses. More initiatives of Youth -Adult Partnership to bridge those gaps.

(William M Nkata , Lead Clinician in CAMHS Psychiatric Liaison services with special interest in MH awareness)