Chinese social media sentiment about the pandemic fluctuated during 2020. Yan Wang and Yuxi Zhang (LSE-Fudan Global Public Policy Hub) use platform data to analyse how these waves of sentiment emerged and shifted, and look at the case of Chengdu Girl, a woman who caught COVID in December of that year.

COVID-19 has profoundly reshaped the way human beings interact. In the era of social distancing, the internet has become the main sphere where social interactions happen, including teaching and learning, work collaboration, political and social participation, and private gatherings. Consequently, private life is frequently displayed, discussed, and moralised in the public space. The individuals subject to public scrutiny are not only politicians or celebrities, but also private citizens. During the pandemic, the externality of individual decisions and behaviour (i.e. their possibility of infecting others) lends legitimacy to an expanded cyber public space, where sentiments about the actions, decisions and even lifestyles of fellow citizens are formed and expressed.

Against this backdrop, we studied the evolving dynamics between Chinese citizens. In particular, we ask when and how individuals react to others’ COVID-related actions and behaviour, including, for example, compliance or non-compliance with the COVID prevention and control measures enacted by the government. We examine if social sentiment change in China follows a cyclical model — as received wisdom during current and previous public health crises would suggest — which reflects the population’s psycho-social status, shifting from fear and refusal, to anger and moralising, and finally to acceptance and action.

Towards the end of 2020, negative social sentiments driven by fear and anxiety were moderated by greater awareness of individual liberty and legal rights, as well as empathy towards fellow citizens

To capture social sentiment shifts during the pandemic, we used social media data extracted from an online platform, Sina Weibo – the equivalent of Twitter in China. Drawing on an extensive data set consisting of more than four million COVID-related posts, we depict the information flows and discussion volumes in the public space. We also assign a sentiment score to each post with machine assisted scoring algorithms, with a higher score signalling more positive sentiment expressed in the text. The quantitative text analysis is further supplemented with in-depth discourse analysis to help us contextualise and make sense of the fluctuations.

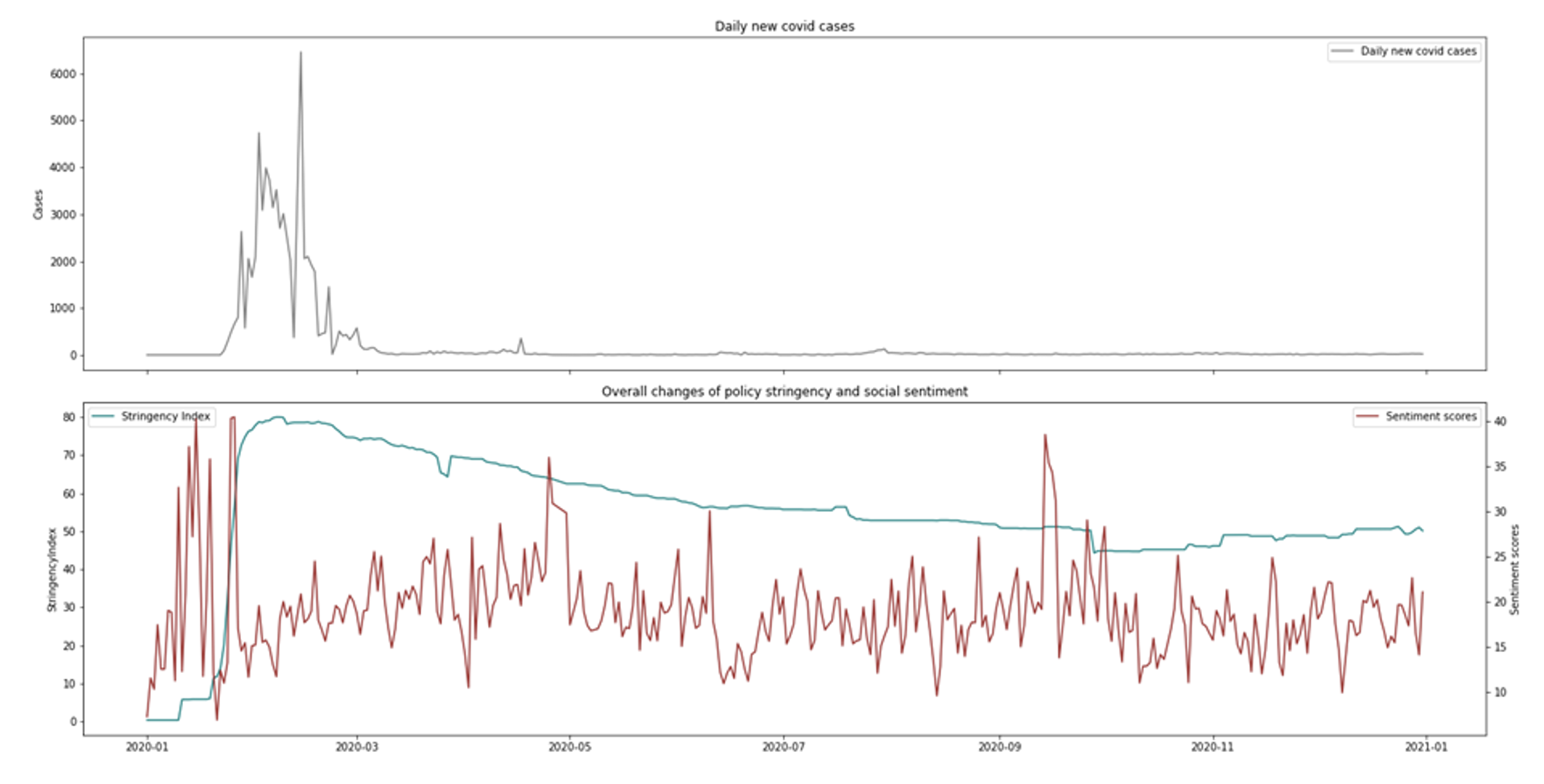

As shown in Figure 1, we plot the daily change of sentiment scores over the whole year of 2020 and juxtapose it with the index of the government’s COVID-19 policy stringency level, as well as newly confirmed COVID cases. The course of sentiment change shows that the cyclical model of psycho-social stages identified in international literature still holds in China, although it shows unique timing and sequence characteristics that are linked to China’s epidemic situations and policies.

Figure 1: General changes in sentiment on Chinese social media in 2020

At the beginning of the pandemic, social media sentiment started to fluctuate before confirmed COVID cases grew significantly or policy responses began to be enacted. These early waves of sentiment reflect that public sentiment was unsettled by the fear of an unknown infectious disease, especially given a lack of trustworthy information.

Then the sentiment score plunged dramatically when Wuhan announced its lockdown on 23 January 2020, unequivocally confirming the severity of the situation. Interestingly, however, it quickly bounced back to the all-year-round high level, mainly driven by people’s support for (and praise of) widespread donations, volunteer mobilisation, and the redeployment of doctors, health workers, and other material resources from all over China to Wuhan and Hubei province. In other societies where COVID at first seemed a distant threat, citizens reacted with fear and sentiments of refusal, voicing suspicion of fellow citizens as virus carriers. In stark contrast, China saw a marked rise in society-wide solidarity at the initial stage of the pandemic.

During the rest of 2020, China mostly kept the disease at bay, with only a few local flare-ups. The local policy environment became characterised by a “new normal”, with some baseline preventative and control measures and targeted lockdowns. For most of the time, people were able to go about their daily lives without too many restrictions. However, the social sentiments expressed online have continued to fluctuate. Acceptance and solidarity-inspired actions dominated online social sentiment at the beginning of the pandemic, but fear, refusal, anger, and moralising later became more tangible in social media posts, and they recurred whenever local epidemic situations fluctuated, implying that the equilibrium between policy control and infectious risk may have been broken.

In this way, citizens are motivated to distinguish the “viral others” and scrutinise fellow citizens’ COVID-related behaviour, which led to a return to the fear and refusal stages that were missing earlier in the pandemic. Our in-depth discourse analysis suggests that social media users frequently denounced behaviour that deviated from norms, as the public took time to redefine the “should” and “should not” of an individual’s actions, decisions and even lifestyles. A vivid example occurred in December 2020, when a young woman known as Chengdu Girl contracted COVID. Others blamed her on social media, putting her in the “viral otherness” group, and attributed her infection to a lifestyle not considered “righteous”.

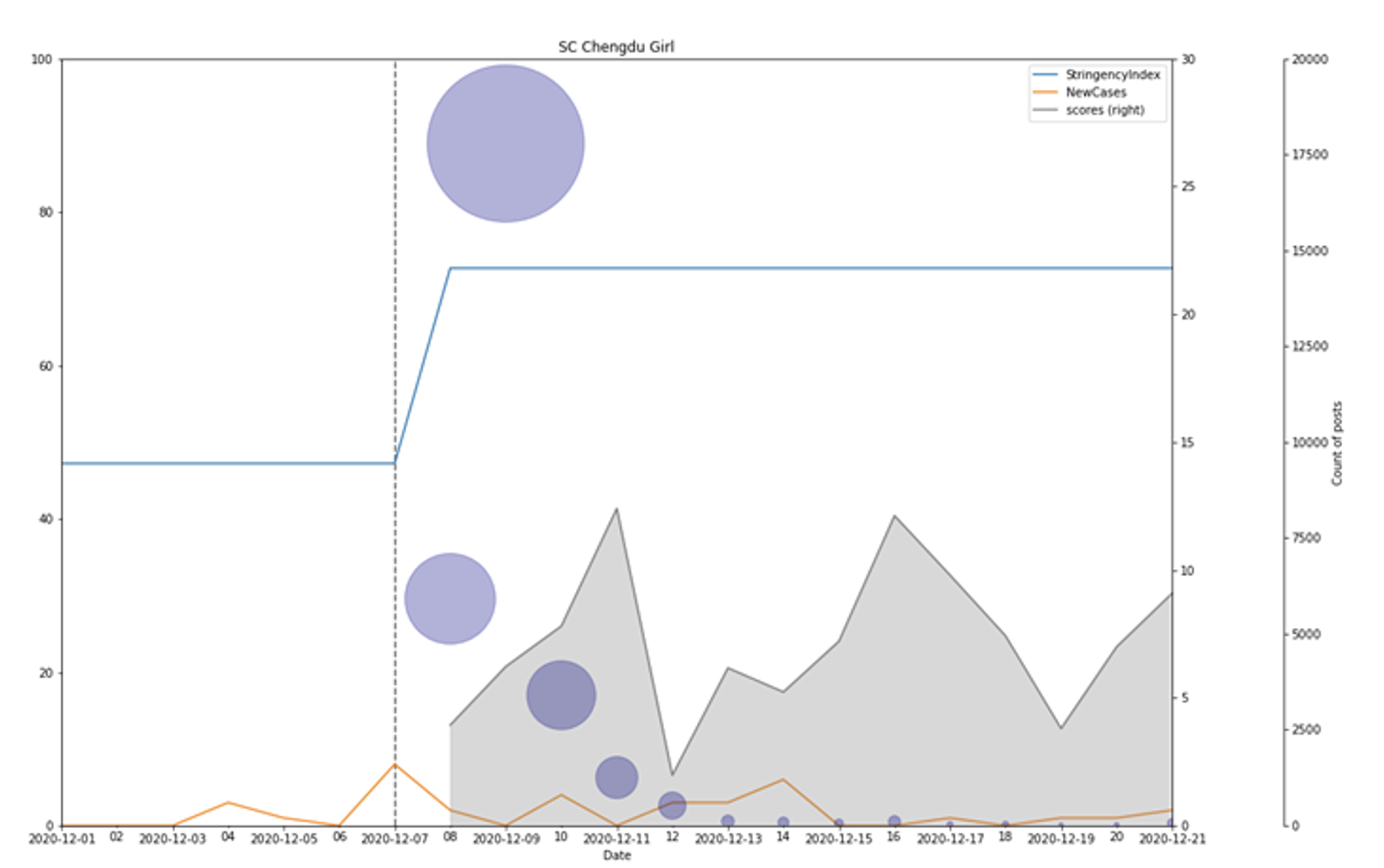

In Figure 2, we plot the sentiment score, policy stringency index, and local COVID cases within a period of one week before and two weeks after the first local COVID case was identified in the city of Chengdu. Chengdu Girl’s personal information was leaked on 8 December, soon after the epidemiological investigation of her mobility tracking was made public — which was supposed to be anonymised. In just two days, posts discussing Chengdu Girl were read 100 million times. Her infection ignited heated discussion online because her mobility tracking seemed to suggest that her daily routine was filled with poker games, manicure treatments, visits to restaurants, tea houses, and nightclubs – a lifestyle social media users labelled as intrinsically prone to infection, irresponsible, and dangerous. Chengdu Girl was frequently teased as a ‘social queen’ and some falsely accused her of working in the sex industry. These discussions – and many other cases – effectively stigmatised and scapegoated fellow citizens for their (seemingly) moral imperfection, and moved those who unfortunately contracted the virus from the “innocent victim” group to the “deserved villain” group.

Figure 2: Sentiment, policy, COVID-19 cases and social media posts about Chengdu Girl

Over time, despite the negative sentiments often directed at the infected, our data also suggest that citizens started to discuss and renegotiate the boundaries of public scrutiny, judgement, and interference imposed on private life during the pandemic. Although no consensus was reached, some agreement did emerge from these discussions. New narratives and strategies emerged, such as ”stepping into other’s shoes” and normative principles regarding the boundaries between the public space and private life. We saw new government policies designed to address the issue of individual privacy and its potential tension with public health concerns. On balance, as society adapted to the pandemic, the cyclical pattern of changes in social sentiment also evolved. Towards the end of 2020, negative social sentiments driven by fear and anxiety were moderated by greater awareness of individual liberty and legal rights, as well as empathy towards fellow citizens.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. It draws on the authors’ forthcoming book chapter “Contesting for Consensus: Social sentiment towards fellow citizens’ COVID-related behavior in China” in the book Pandemic Narratives in China and the World: Technology, Society, and Nations, edited by Guobin Yang, Bingchun Meng and Elaine Yuan. A pre-print version of the chapter is available on SSRN.